The G7 Summit in Hiroshima is being held at the time of a significant milestone in world history. There is no sign of the end of the war in Ukraine, which even poses a nuclear threat, something that was considered to have become a thing of the past since the end of the Cold War. The latest war has made it difficult for many countries to procure energy, and price hikes are threatening people's lives globally.

The intensifying conflict between Japan, the United States and European countries on one side and China and Russia on the other has divided supply chains, and this has had serious impacts on the basic structure of the economy.

Through the international division of roles based on differences in production efficiency, all countries can receive the benefits of trade. This has been considered to be the most basic proposition in economics since having been formulated around 200 years ago by David Ricardo, a British economist who developed classical economics. The philosophy of free trade has contributed to the expansion of world trade after World War II under the frameworks of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) although it has encountered various challenges.

In particular, innovative advancements of information and communications technologies since the end of the 20th century have accelerated the globalization of capital flows and trade. However, this move stopped suddenly, and companies are now struggling to secure supply chains as they are faced with new sources of risks.

But this is not the first time we have experienced this. The first G7 summit (then G6) was held at Chateau de Rambouillet in the suburb of Paris in November 1975, when advanced Western countries were facing serious stagflation due to sharp oil price increases by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), the crisis that came to be called the first oil crisis.

In 1974, consumer prices increased by over 20%, and Japan registered negative growth for the first time after World War II. At the first G6 summit meeting, which was held merely a few years after the collapse of the Bretton Woods system (under which 1 US dollar = 360 yen), member countries set up a common target to curb inflation and achieve sustainable economic growth and also discussed ideal exchange rates under the floating exchange rate system.

Surprisingly, Japan was the most successful of these countries in navigating the tumultuous 1970s. Learning lessons from serious inflation at the time of the first oil crisis, during the second oil crisis (1978-1982) the Japanese economy performed favorably when compared internationally, both in terms of commodity prices and economic growth. Japan’s wage flexibility attracted the world's attention as its secret weapon.

Resource constraints, which were revealed in the 1970s, also spurred Japanese manufacturing. The Japanese automobile industry succeeded in developing energy-efficient vehicles and became front runners in the world during this period. In the 1980s, as evident in the book written by Ezra Vogel, Japan as Number One, Japanese industry made significant headway thanks to active innovation (technological revolutions), which caused serious trade friction with the United States.

◆◆◆

The problems that the world currently faces are different from those of 50 years ago. In the 1970s under the Cold War framework, the world was not peaceful, but there was no impending crisis that might cause a collision between the East and West after the end of the Vietnam War. However, at present, the rules-based world order is being severely tested due to the perpetual war in Ukraine. This issue will be the most important theme of the G7 Summit to be held in Hiroshima, as one of only two cities that have been ravaged by a nuclear weapon.

There is another significant difference between the 1970s and the present. The period from the 1950s to the 1960s was a golden age, when advanced capitalist countries enjoyed high growth, the reduction of income gaps and decrease in inequality. Then in the 1970s, sharp oil price increases stopped the high post-war economic growth and caused rampant inflation. On the other hand, at present, capitalist countries are facing the confusion of the world economy and inflation amid a long-term economic downturn and the expansion of income gaps. Globally, people's frustration is increasing against the background of expanding income gaps.

Financial and monetary policies that are used to respond to various problems also face stronger constraints than in the 1970s. As a result of the expansionary fiscal policies to combat the oil crisis, the total value of government bonds in Japan increased nine-fold between 1975 and 1985, from 15 trillion yen to 134 trillion yen.

Nevertheless, this cannot compete with the current situation, where the total value of government bonds amounts to 1,000 trillion yen: over double the nation’s GDP. This is not only a problem in Japan; the national finances have also deteriorated rapidly due to COVID-19 in many other countries. Former UK Prime Minister Liz Truss, who assumed office in September 2022, was forced to resign only one and a half months after being elected when she published a government spending plan without budgeting for it. In the United States as well, the federal government reached the statutory debt limit.

Regarding monetary policies, there were no constraints on the zero-rate policy in the 1970s. The official discount rate, which was an important policy tool, was raised to 9% in December 1973 after the first oil crisis but was gradually lowered to 3.5% by March 1978. After the occurrence of the second oil crisis, it was raised again to 9% in March 1980 but was lowered to 2.5% by February 1987. Such flexible monetary policy is no longer possible.

◆◆◆

While individual countries are forced to maintain their policies, the need to maintain the stability of the global financial system is paramount, for which international cooperation is essential. At present, we must prevent the effects of a bankruptcy of a mid-sized U.S. bank, the financial difficulties of the Credit Suisse Group, and the debt problems of developing countries from expanding to create a global crisis. However, the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors Meeting that was held in Washington this April failed to show solidarity on these issues. The leadership of the G7 member countries is being tested.

Meanwhile, why have advanced countries been suffering from prolonged stagnation while India and other countries that are referred to as the Global South are experiencing rapid growth? Slow growth is ultimately caused by a lack of innovation, and some say that the prolonged stagnation of advanced countries is due to depleted innovation sources. People say there is nothing left to accomplish, but that is obviously not true.

It is widely recognized that global warming and the arrival of a super-aging society are serious problems for all people, but efforts to solve them have just started. Innovation is obviously much needed, even just in those two fields of "green" issues (the environment) and "silver" issues (the aging of the population). For that reason, it is indispensable to create international rules, as shown in efforts for decarbonization. The same applies for the control of AI and other new technologies. It is expected that discussions in these areas will progress at the G7 Summit.

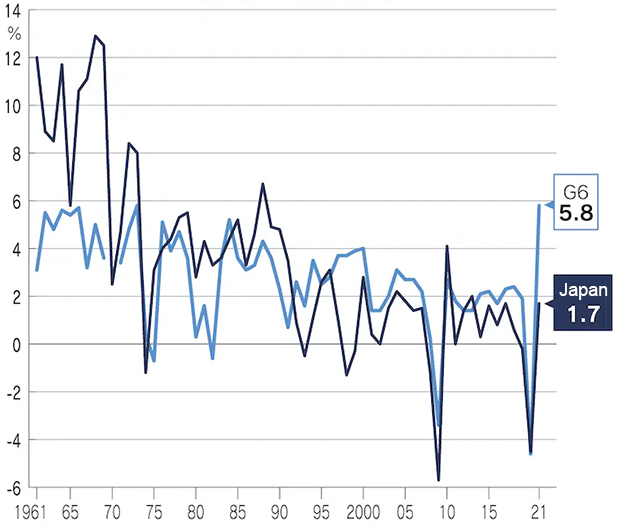

In addition to trends in the world economy, we are interested in trends in the Japanese economy. The figure below shows the real growth rates of Japan and the other six advanced countries (G6). It is widely known that Japan's growth rate was very high during the rapid growth period in the 1960s, but even after that, Japan's growth rate remained higher than the other six countries until 1991, when the bubble economy burst. However, for the 30 years since 1992, Japan's growth rate has mostly been below the average growth rate of the G6 countries.

(on a dollar basis in 2015; year on year difference)

(Source) Prepared by the author based on data from the World Bank.

The other G6 countries all have longer histories as capitalist economies than Japan and are mature. At the time of the global financial crisis in 2008, the countries of the G7 all registered significant negative growth, but Japan was noticeably slower in its recovery than the other six. The same can be said for the status of its recovery in 2021 after the economic slowdown in 2020 due to COVID-19. The Japanese economy is structurally more vulnerable than the other G6 countries, because capital investment and R&D investment are much more sluggish in Japan than in other advanced countries despite its high savings ratio.

The G7 countries must individually maintain strong economies while being firmly united in order to maintain their position as the leaders of the world economy. The government of Japan needs to be especially mindful of this reality.

* Translated by RIETI.

May 10, 2023 Nihon Keizai Shimbun