A “New Capitalism” is the centerpiece of the economic policy of the administration of Prime Minister Fumio Kishida. The new capitalism is apparently intended to maximize capital benefits by creating a virtuous circle of growth and redistribution through economic and social reform initiatives to correct the various flaws that have been generated by the traditional capitalism.

From the beginning, the Kishida administration has emphasized the “newness” of its signature policy particularly because of the focus on a redistribution strategy. However, specific measures announced by the administration, such as raising the wage levels, promoting human resource investment and maintaining the middle class, are nothing new, as previous governments already attempted to do those things. If Kishida wants to emphasize “newness,” it is essential to rethink the significance and logic behind the new capitalism.

◆◆◆

What I consider to be particularly important among the specific measures announced under the banner of new capitalism are raising the wage levels, promoting human resource investment, and responding to climate change. According to some opinions, the new capitalism, if it attaches importance to human resources and also requires the resolution of social challenges, may actually simply be “stakeholder capitalism.”

However, stakeholder capitalism itself is also not something new, since it is basically the embodiment of the traditional Japanese economic system that prospered until the 1980s. What I am worried about is that stakeholder capitalism has recently tended to be discussed and understood as a concept that is in opposition to shareholder capitalism and market capitalism.

If shareholder capitalism is to be rejected, then the principle of companies pursing the maximization of profit should be abandoned, which would lead to neglecting the responsibility of maximizing corporate value. Companies neglecting that responsibility are bound to be shaken out of the market. That is one of the cardinal rules of capitalism.

However, even if companies operate with greater consideration for stakeholders, including employees, and if they go beyond that and consider ways of making societal contributions, these actions are not necessarily inconsistent with their profit maximization behavior. This point has been explicitly argued by Jean Tirole, a prominent French economist who won the Nobel Prize in Economics. The key to his argument is the length of the time horizons that companies take into consideration.

For example, although investing in employees is initially a cost for employer companies, the investment will yield profit with the passage of time as its effects are reflected in employees’ skills and performance. It may take an even longer time before companies can enjoy the benefits from making societal contributions. However, if a sufficient period of time is allowed, making societal contributions can be reconciled with pursuing the maximization of corporate profit because doing so works to increase the credibility and reputation of companies. In other words, operating with greater consideration for stakeholders can be viewed in the context of an intertemporal profit maximization problem in that doing so means attaching importance to long-term profit.

If companies operate with greater consideration for a wider range of stakeholders, it results in, to use the terminology of economics, the internalization of the interests of additional stakeholders, which they previously treated as externalities, and the lengthening of their time horizon. If companies limitlessly expand the scope of stakeholders whose interests are taken into consideration, their time horizon also approaches infinity. It should be kept in mind that if that happens, the behavior of companies will essentially become infinitely similar to the government’s ideal behavior in that they would ultimately seek to maximize the benefits for the entire population of the country.

Therefore, it can be said that while stakeholder capitalism pursues the maximization of profit from the long-term perspective, shareholder capitalism seeks to maximize profit from the short-term perspective. The economic system that supported Japan in the postwar high growth period through the 1980s was founded on a long-term, relationship-based transactional arrangement that is compared to an (infinitely) repeated game as referred to in the realm of game theory. Because of that arrangement, it can be said that companies were allowed to have a long-term perspective. By contrast, the United States’ fixation on shareholder capitalism in the 1980s was criticized as being short-sighted.

In light of the above, some people may argue that stakeholder capitalism, which is consistent with the government’s mission of solving the problems that society faces and which does not conflict with corporate profit maximization, should be promoted (however it is not truly new). The problem is that it has become more difficult than before for Japanese companies to operate based on long time horizons because of the low growth of the Japanese economy and increasing uncertainties.

It is often pointed out that human resource investment by Japanese companies has been declining over a long period, and this probably has something to do with the shortening of the time horizon mentioned above. In present-day Japan, the traditional form of stakeholder capitalism, which is predicated on companies operating under a longer time horizon, may be difficult to uphold as a goal.

On the other hand, there have been increasing signs of the beginning of a new sort of capitalism that may be dubbed “stakeholder capitalism 2.0.” For example, there is a growing movement among excellent Japanese companies to further the working style reform and improve business performance by enhancing employee wellbeing (physical, mental, and social wellbeing). Employee wellbeing is a wide-ranging concept encompassing factors such as a sense of fulfillment and work engagement (employee motivation, vitality and dedication).

Together with Professors Miho Takizawa of Gakushuin University and Isao Yamamoto of Keio University, I have used the Smart Work Management survey, which covered major listed companies, to analyze employee wellbeing’s determinant factors and impact on business performance, and accumulated results that indicate its importance.

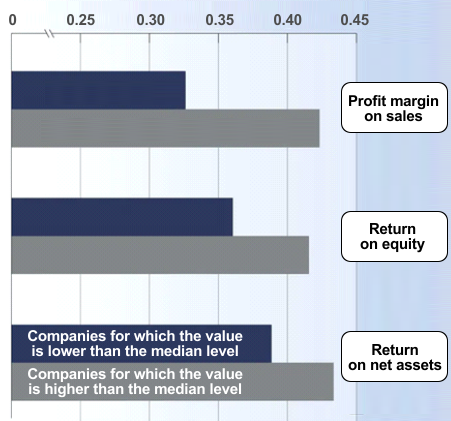

For example, companies with a high level of employee work engagement tend to possess a high level of profitability (see the figure below, particularly in terms of the profit margin on sales). Another prime example is the finding that health-oriented management initiatives improve business performance. It appears that compared with traditional human resource investment, which is intended to develop job skills, enhancing employee wellbeing delivers a return more quickly.

◆◆◆

The conflict between capitalists and workers has long been a feature of capitalism. However, the conventional view that sees an antithetical relationship between workers and companies—that is, an idea that what benefits workers only costs companies—is rapidly becoming outdated. One factor behind that change is the fact that assets created by workers in the broad sense, including intangible assets, are replacing physical assets as the wellspring of corporate productivity growth.

Efforts to resolve societal challenges may be starting to bring benefits earlier than in the past. For example, investors’ explicit assessment of such efforts, as exemplified by ESG (environmental, social and governance) investment, is beginning to have a direct impact on corporate value. In addition, as consumers are increasingly becoming sensitive to efforts to resolve environmental problems and other social challenges, the additional direct impact on sales growth cannot be ignored.

Moreover, the concept of “purpose-based management,” which clarifies companies’ raison d'être and missions, has recently been attracting attention. Companies that practice this concept gain the of their employees by explicitly stating what social contributions they would like to make beyond pursuing the maximization of profit. That is becoming more and more important in order to ensure that competent employees with diverse backgrounds undertake their jobs with a sense of unity.

I am looking forward to the spread of “stakeholder capitalism 2.0,” under which companies enhance employee wellbeing and contribute to the resolution of societal problems while simultaneously pursuing higher corporate value, with these activities complementing each other—“Doing good for others will do good for you as well,” as the Japanese proverb says.

* Translated by RIETI.

May 10, 2022 Nihon Keizai Shimbun