One of the key features of the dynamic engagement of all citizens plan on which the Shinzo Abe administration will make a Cabinet decision in May 2016 is equal pay for equal work.

The government has already committed to preparing to change the law, promptly establishing guidelines on how much of a wage gap is unfair and presenting case studies. Moreover, a study group has already been formed to prepare for the realization of equal pay for equal work and has begun discussions on the issue. One area of great interest is how concrete the policies presented will be.

Improving the treatment of non-regular employees in order to correct the polarization of the Japanese labor market is a long-standing issue and has not yet been fully addressed. But why is the administration taking the approach of trying to realize equal pay for equal work?

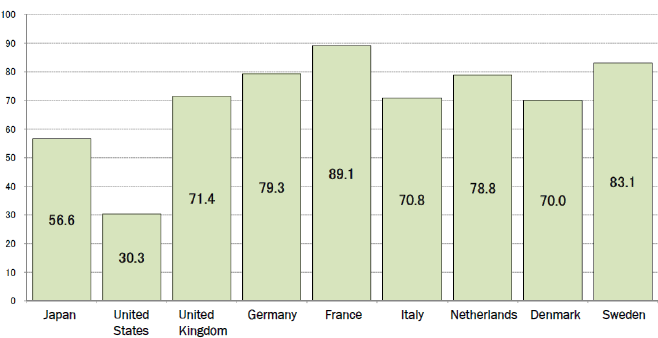

As far as can be seen from the discussions of the aforementioned study group and Prime Minister Abe's explanation to the Diet, the starting point is that part-timers in Japan make some 40% less per hour than full-time workers. In several European countries, by contrast, the gap is only about 20% (see Figure). If we are to achieve equal pay for equal work, significantly shrinking this wage gap is a prerequisite.

♦ ♦ ♦

There are, however, a number of things to be mindful of if we set policy based on such international comparisons. First, if we take a narrow definition of equal pay for equal work as "the worker always gets the same pay for doing the same work at any given time," it does not necessarily mean that the above wage gap disappears, even if we achieve equal pay for equal work.

For example, students, housewives, or anyone with the burden of school or housework may prefer part-time work to full-time work, and to the extent that this is true, they are willing to take lower pay. And part-timers who dislike long commutes may wish to work as close to home as possible, while their employers for their part can easily pay lower wages if they successfully confine these workers and exercise a monopoly on them.

From the business' perspective, however, there are certain fixed costs for every employee. Total labor costs do not rise proportionally to employees' working hours. Insofar as part-timers putting in short hours is more costly to businesses, it makes economic sense that their wages are lower. Wage gaps caused by such factors can occur as a matter of course, even if the work is the same.

Second, debating whether the average wage gap between full-time and part-time workers is too great is not necessarily appropriate if it is based on a simple international comparison. If the capabilities and work of full-time and part-time workers differ, that would be reflected in their average pay. If full-time workers on average have a higher educational background or more years of work experience, for example, naturally they will receive higher pay.

Even if we compare statistics internationally, we have to consider worker attributes such as these and adjust for such factors. Then we can focus on the remaining wage gap.

For example, in a 2007 international comparative analysis by Université Libre de Bruxelles Associate Professor Síle O'Dorchai et al., male full-time workers out-earned their part-time counterparts by 24% in Belgium, 28% in Denmark, 28% in Italy, 16% in Spain, 149% in Ireland, and 67% in the United Kingdom. However, the percentage of the gap in each case that could not be explained by adjusting for various worker attributes vanished in the case of Denmark, but was still about half as great in Italy. So there is great variance in the wage gap after making these adjustments, even if the gap was about the same before adjusting.

Some care must be taken in light of the fact that the numbers for the part-time wage gap will vary even within the same country depending on the statistics and techniques used. However, to generalize existing research, the gap is relatively large in English-speaking countries, while the gap disappears after adjustment in certain northern Europe countries. It has even been reported in several studies that part-timers enjoy higher wages in Australia, after adjustment.

As for Japan, there are few studies that strictly analyze wage gaps between different employment patterns.

At RIETI, I am conducting joint research with Recruit Works Institute's Chief Researcher Koichi Kume, Chiba University Associate Professor Shinpei Sano, and Aoyama Gakuin University Associate Professor Kengo Yasui. The wage gap between regular employees and groups such as contract employees (a class of non-regular employees that closely resembles regular employees) is about 37%. After adjusting for factors including educational background, age, years of continuous service, marriage status, number of children, place of residence, industry, or duties, however, the remaining gap was only about one-fourth as much. While this is a provisional result, it indicates a single-digit gap.

♦ ♦ ♦

An important policy implication from the part-time wage gap research that focuses on Europe is that in the United Kingdom, which has a relatively large wage gap, there is a problem of "occupational segregation."

London School of Economics Professor Alan Manning et al. indicated in a 2008 paper that the full-time/part-time wage gap for women in the United Kingdom was 25%, but dropped to only half of that—about 12%—after adjusting for standard demographics, and moreover, the gap shrunk to just 3% after adjusting for work duties as well. This suggests that differences in the work of full-timers and part-timers are a major factor in the wage gap.

Actually, in the United Kingdom, full-time female workers who switch to part-time status often have to change workplaces or work, and when they take on lower-level work, their pay tends to fall accordingly.

In a 2009 paper, University of East Anglia Professor Sara Connolly et al. noted that of the highly skilled women who switched from full-time to part-time status, 26% took on work of a lower level (the number was 43% if the woman changed workplaces), and wages dropped by 32% as a result of the change. Moreover, women who returned to full-time status in the same work as before received about 40% lower wages than if they had continued as full-time.

For example, half of women in professional occupations took on lower-skilled work when they changed to part-time status, and two-thirds of nurses switched to nursing care work. In neither of these cases were women able to make full use of their skills when working as part-timers.

In the United Kingdom, although the gap is not so great when the work is the same, "occupational segregation"—the major difference in the nature of full-time and part-time work for women—is a problem. Manning et al. insist that better jobs need to be made available to part-time workers. Recent analysis of other European countries confirms that this "occupational segregation" is the biggest factor in wage gaps.

♦ ♦ ♦

In the case of Japan, further analysis is necessary on the severity of the problem of segregation of duties. Assuming this to be a major factor, however, equal pay for equal work is an uncertain way of shrinking the part-time wage gap. Rather, introducing a Dutch-style flexible work-hour system to enable full-time workers to switch to part-time status without changing workplace or work would be the key.

Additionally, research from several countries has shown that, while there is no part-time wage gap for young people at their first jobs, the gap grows markedly as they work longer in part-time jobs. Implementation of a "principle of time-proportionality" that accounts for years of continuous service even for part-timers' wages and other treatment, as in an EU directive, should be considered.

* Translated by RIETI.

May 17, 2016 Nihon Keizai Shimbun