On September 30, 2024, immediately after the election of Mr. Shigeru Ishiba as the new president of the Liberal Democratic Party, Tokyo stocks plummeted. This plunge was ridiculed as the "Ishiba Shock" as one of the causes is said to have been his positive stance toward strengthening taxation on financial income.

That said, the “100-million-yen wall” in Japan—the phenomenon where Japanese taxpayers with annual incomes over 100 million yen effectively pay less tax (taxes on total income)—has long been considered problematic. Taxation on income exceeding 100 million yen is regressive, suggesting that the redistributive function of taxation (rectification of income disparities) is impaired.

Japan’s income tax system is progressive, with a maximum tax rate of 45% for wages and business income. On the other hand, financial income, such as interest, dividends, and capital gains are taxed at a flat rate of 15% (20% total with local taxes included). As higher-income individuals tend to have a higher ratio of non-salaried financial income, because of this ratio, they tend to have lower overall income tax burden.

In order to rectify this situation, the tax reform for FY2023 introduced a measure that imposes an additional tax on individuals with incomes higher than three billion yen, so that their income tax burden rates will not become lower than 22.5%; however, this measure will only affect a limited number of taxpayers.

When considering taxation on financial income, its relationship with social insurance premiums also needs to be taken into account. Currently, social insurance premiums are calculated based on earned income and business income for regular workers (employees). For non-regular workers, self-employed workers, or the elderly, who are insured under the municipal health insurance programs or long-term care insurance, respectively, total income, including financial income reported in tax returns, is the basis for the calculation of insurance premiums.

The total income includes not only wages and pensions, but also financial income when a person files an income-tax return. However, for individuals whose financial income is subject to withholding tax in specified securities accounts or investment trusts, filing income-tax returns is not a requirement, and whether a tax return is filed or not becomes relevant to their calculation of insurance premiums.

This inconsistency in social insurance premium calculations based on income type or whether or not filing tax returns is a requirement is unfair. One potential solution is to include financial income uniformly in the calculation of insurance premiums.

In the United States, in consideration of the fact that taxes are paid from earned income to fund the public healthcare system for the elderly, a new system was introduced in 2013 which imposes an additional tax on net investment income, including from interest and dividends, for taxpayers whose total income is above a certain level. The Contribution Sociale Généralisée (introduced in 1991) in France, which includes social insurance premiums in tax amounts, is imposed not only on wages and pensions, but also on financial income.

◆◆◆

One concrete approach to strengthening taxation in Japan would be to raise the tax rate on financial income from the current rate of 15%, while maintaining separate taxation. Alternatively, some believe that financial income should be combined with other income and be subject to progressive taxation. However, there are three points to keep in mind regarding progressive taxation.

First, capital gains are accumulations of past income. Suppose that a person had capital gains totaling 100 million yen from sales of securities or land this year but has had no gains in other years. It cannot be said that the person's tax burden-bearing capacity is high over a lifetime basis.

To address this problem, some form of income leveling would be required. For example, if a person's capital gains for this year amount to 100 million yen, 10 million yen would be added to the person's annual income for taxation for 10 years. That would make it possible to avoid a single, significant increase in income tax due to the sale of shares or land, etc.

Second, taxation on capital gains depends on when the gains are realized. Even if the value of shares a person holds increases, no tax is imposed until the shares are sold. Taxpayers could delay the timing of the sale in order to postpone tax liability. Under the progressive taxation system in which taxation amounts increase with the value of capital gains, taxpayers are effectively encouraged to postpone taxable events (resulting in a lock-in effect).

On the other hand, taxation based on the fair market valuation of shares does not cause a lock-in effect. However, the treatment of financial assets whose value is difficult to assess, such as unlisted shares that are not traded on the market, and the difficulty for taxed individuals with no cash on hand would be significant issues that need to be addressed.

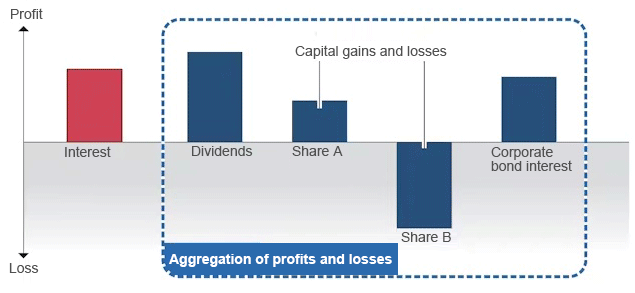

The third point relates to the coverage of aggregation and totaling of profits and losses in financial income. The aggregation of profits and losses refers to the offsetting of losses from the sale of shares with the profits of other financial income, such as dividends and interest. For taxation on financial income, not all types of profit or losses from financial income can be aggregated. Only dividends, capital gains from securities, and interest on corporate bonds can be aggregated (Figure 1).

Profits from transactions of crypto assets are treated as miscellaneous income that cannot be aggregated with other financial income. Interest earnings are also excluded because name-based aggregation is impossible for persons who have accounts in different financial institutions.

In order to effectively implement name-based aggregation, it is essential to link an account holder's individual number (under the “My Number” system in Japan) to their financial account. However, due to political opposition to the national government gaining the ability to capture individuals' financial assets, this has not progressed. For this reason, at present, even if progressive taxation were pursued, there is no mechanism which would allow for the aggregation of individuals' financial income.

◆◆◆

Regardless of whether separate taxation or progressive taxation is implemented, consideration should be given to avoid hindering the efforts of working generations to build assets for retirement. Therefore, it is necessary to expand tax-free savings for which interest and dividends are exempt from taxation. Tax on financial income should be imposed on the portion that exceeds that limit.

In 2024, the national government made the NISA program permanent and significantly raised the limits for annual contributions. The NISA program is classified as a “TEE model” investment (Taxed, exempt, exempt), meaning that the initial contribution is taxed as it is non-deductible, but subsequent operational benefits and withdrawal are tax-free.

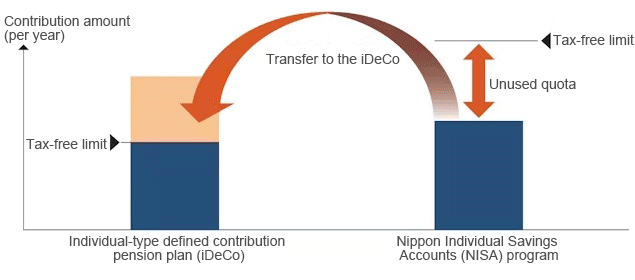

The national government may also expand the individual-type defined contribution pension plan (iDeCo). The iDeCo operates under the EET-model under which the initial contribution and investments are undertaken tax-free, but all benefits are taxable. Combining the NISA program and the iDeCo to unify the annual tax-free contribution limits, and more specifically, allowing unused tax-exempt contribution limits to be carried across to other tax-exempt savings would increase convenience for users (Figure 2). In countries like the United Kingdom and Canada, unified tax-free contribution limits have already been introduced.

As neither the iDeCo nor the NISA program are meant to create inheritances, it would be appropriate to limit the period during which people can hold assets tax-free. The NISA program in Japan currently has no set upper age limit for withdrawals. In contrast, in the United States, the Individual Retirement Account (IRA) plan, a tax-free savings system in the United States, requires account holders to withdraw their money by the age of 72. The Registered Pension Plan (RPP) in Canada also sets the upper age limit for withdrawal at 72 years of age.

It would be appropriate to devise methods of directing the assets of wealthy individuals toward investments in startup companies and other ventures. The FY 2023 tax reform adopted a measure which would provide a tax exemption on up to 2 billion yen of financial income from securities sales (capital gains) for individual investors who reinvest capital gains into startup companies.

This concept is generalized in the mechanism of an “expenditure tax.” Under this system, taxes are based on the income amount that remains after deducting investments. As long as high-income earners reinvest their wealth into society, taxation is deferred. On the contrary, when capital gains or dividends are withdrawn for personal consumption, or in other words, for negative investment, the tax burden increases. The NISA program and iDeCo are therefore types of expenditure tax.

An expenditure tax is similar to a consumption tax in the sense that its taxation base is based on consumption. However, unlike a consumption tax, it is a direct tax where individuals are the taxpayers and under which progressive taxation is possible in the same manner as in the case of income tax. If the national government intends to strengthen taxation on financial income, it should devise methods to avoid hindering economic activity, including the introduction of expenditure tax systems.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

November 6, 2024 Nihon Keizai Shimbun