Efforts toward digital transformation (DX) are accelerating amid the COVID-19 crisis. In particular, the spread of remote work has weakened resistance against the introduction of information and communications technology (ICT) and artificial intelligence (AI), essentially removing all of the obstacles to digital transformation. Amid the expanding DX movement, I will map out the vision of how Japanese companies' personnel management and organization should change based on recent studies.

♦ ♦ ♦

Versatile digital technology which has a large variety of applications, could have various effects on companies' personnel management and organization. In the field of economics, in many cases, digital technology is divided into the following three categories: information technology (IT), which reduces information acquisition cost; communications technology (CT), which reduces communication cost; and automation technology (robotics and AI), which replaces human labor that performs routine tasks.

Four effects of digital technology on personal management and organization are particularly noteworthy as explained below.

First, although the relationship between the number of years of experience and productivity (productivity curve) is typically upward-sloping, meaning that productivity rises in line with the accumulation of experience, it gets flatter or could even be downward-sloping as existing skills become obsolete quickly among jobs in which ICT and AI technology are used extensively.

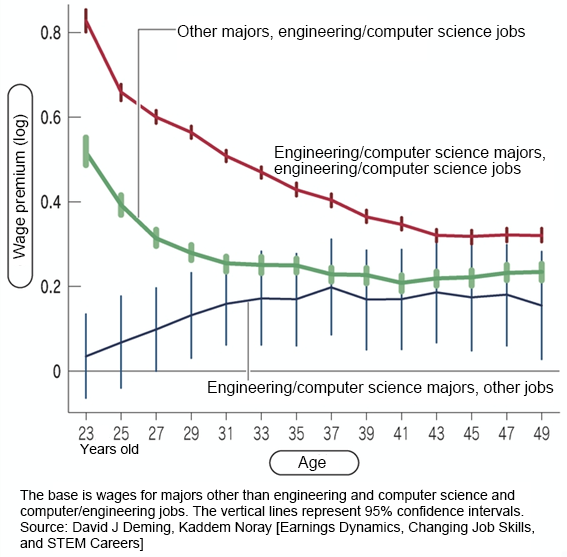

Professor David Deming at Harvard University and his student examined the relationship between wages and the pace of change in skills requirements in various fields as measured based on skill requirements for job postings available from job information websites. Their study showed that in fields with rapid skill turnover, where existing skills becoming obsolete and are replaced by the need for new skills, the wage premium compared with other fields is at its highest immediately after graduation, and that the wage curve, which represents the relationship between age and wages, becomes flat. From the figure below, it is clear that the wage premium for workers in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) fields decreases in line with age.

Second, in theory, a decline in communication cost lowers the cost of information integration and communication between the upper and lower layers of an organization and promotes the centralization of decision-making. On the other hand, a decline in information acquisition cost leads to decentralization, as it enables informed decisions for people at the lower layers of an organization as well as encouraging information-sharing among employees. According to the results of empirical analyses conducted in the United States and Europe, the centralization tends to occur in the upper layers of an organization, while the decentralization tendency is strong in the lower layers.

Consequently, the number of subordinates supervised by a single middle manager increases, which results in the flattening of the organization, with the number of middle managers reduced. Because of the introduction of robots and AI, errors decrease and the number of employees with middle-level skills who need to be supervised by senior employees also falls. As a result, the time necessary for overseeing and giving instructions to the rank and file is reduced, leading to a further decrease in the number of middle managers.

Third, it is becoming more important to have the skills of the employee match the job (putting the right person in the right place). That is because productivity gaps due to differences in the level of competency become wider as human labor performs more sophisticated, non-routine tasks as a result of substitution by automation, and also because the cost of searching for workers with the right skills decreases. Wage gaps widen because of the larger productivity gaps and additional market pressures from the increased mobility of workers within and outside the organization.

Fourth, long-term incentives gradually disappear. A decline in the number of middle managers leads to a further fall in the chance of promotion, which has already been harmed by stagnant economic growth. The flattening of the productivity curve means that many companies find it difficult to maintain seniority-based wages. The need will grow to strengthen short-term incentives in order to maintain employee motivation.

♦ ♦ ♦

The abovementioned changes are gradually affecting how jobs are designed and how employees are evaluated. The impact is appearing mainly in the form of a shift toward job-specific employment contracts which are characterized by job descriptions and narrower discretionary power of employers than was previously the case. In the postwar era, Japanese companies employed workers with the discretionary power to assign employees to any job they wanted in exchange for job security. This has encouraged workers to invest in firm-specific human capital and accept any job rotation or transfer as part of the relational contract, giving employers greater flexibility in adapting to demand and technological shocks. In recent years, however, the adverse effects of such employment practices have become more noticeable. I believe that the ideal employment system will be the one based on job-specific employment contracts with the following three pillars: (1) standardization of jobs, (2) decentralization of decision authority in personnel management, and (3) autonomous career development.

The reason why standardization has become necessary is closely related to the abovementioned effects. First, due to the flattening of the productivity curve, it has become necessary to also flatten the wage curve, which previously was based on the seniority-based wage system. Second, as the importance of matching jobs and skills has grown, it has become necessary to better clarify skill requirements through standardization of jobs. Third, in order to increase short-term incentives, it has become necessary to reflect market wages in corporate wage structures.

Japanese companies formerly concentrated personnel management responsibilities, including recruitment, training and assignment, within the personnel management division, in order to help employees acquire broad experience and develop a network of connections through well-planned assignment to different departments within their companies, thereby enhancing firm-specific coordination capabilities. However, as a result of a fall in the number of workers promoted to management positions and the progress in standardization of business processes due to the use of ICT, the advantage of accumulating firm-specific human resources has declined.

Rather, it is more reasonable to shift to a decentralized system in order to promote more efficient matching of jobs and skills and to increase the involvement of middle managers in the training of rank-and-file employees. To do that, it is necessary for front-line managers to change their mindsets regarding the shift.

Autonomous career development has become more important because the need for re-skilling has grown due to the increased pace of technological innovation. However, the level of private-sector investments in human resources in Japan remains low. To speed up skills development, it is essential to both increase corporate investment in training and to enhance employee motivation toward learning.

To that end, it is imperative to develop awareness regarding career ownership—awareness about the need to develop one's own career—among employees and provide them with the information that is necessary for career development. It is also necessary to promote the standardization of jobs and skills and to develop a database of information on employees' job experience and skill development, thereby supporting career planning.

Introducing this type of new employment system that is based on job-specific employment contracts will cause an increase in human resource investments. Although some people argue that shifting to job-specific employment increases the turnover rate and reduces human resource investments by companies, I believe otherwise. Under the conventional human capital model, the motivation for making investments may decline. However, the conventional model fails to account for the fact that hiring companies may compete to attract new graduates and mid-career workers by offering more favorable provision of human capital investment. Nor does it take into consideration the returns from acquiring workers with exceptional managerial talent.

Under an ideal employment system with aforementioned three pillars, employees do not expect a pay increase unless they improve their skills. As a result, employees and job applicants become more motivated to make efforts at self-improvement and more willing to look for employment in companies committed to employee training. To attract competent workers, large companies increase investments in employee training. As hiring workers with potential as future managers may deliver very high returns for employer companies, additional costs resulting from an increase in the turnover rate can be recovered. This view is supported by the fact that U.S. and European companies are allocating a large portion of their resources to employee training.

Within the ongoing DX revolution, it is highly likely that required skills will change more quickly than in the 1980s, when the use of personal computers spread. If a gap abruptly emerges between supply and demand of skills, investing in reskilling employees will become the greatest management challenge even in the United States and Europe, where the job market for mid-career workers is well developed.

Many U.S. companies have started to make massive investments in employee training toward the reskilling of their employees. While a sense of crisis is motivating action even in the United States, where labor in the STEM fields is available in abundance and where the job market for mid-career workers is well developed, Japanese companies have been slow to take action.

Although Yahoo recently announced a plan to retrain its entire workforce of 8,000 or so employees to develop advanced IT skills, I have not heard about other companies planning a reskilling initiative on a similar scale. Probably, that is mainly because most Japanese companies are failing to envision their future business model amid the ongoing technological innovation as well as lagging in developing talent management databases.

In such an uncertain business environment, it is necessary to organize a management team with diverse backgrounds and make management decisions based on data and experiments. Companies should become more active in hiring young people who have acquired new skills, foreign workers, and workers from different business sectors. In addition to reskilling of employees, there are many other challenges for Japanese companies. These include abolishing outdated Japanese personnel management practices, including the late promotion policy in which even qualified employees are not promoted until they reach a certain age and the promote-from-within policy in which only those who stay with the company throughout their entire career get promoted to top management, in addition to reforming the process of selecting and training managers.

* Translated by RIETI.

February 9, 2022 Nihon Keizai Shimbun