The phrase “education gap” has come into wide use. It refers to inequality in educational opportunities among children due to differences in the family environment. While the “family environment” includes various elements, the parents’ economic situation may be the first thing that comes to many people’s minds. To be sure, economic difficulties limit the scope of options as to which schools to send children to or whether or not to send children to higher education, for example. As a result, a generation-to-generation chain of poverty may arise.

Although this description of how an education gap is created may look plausible at a glance, parents’ incomes are determined by various factors, including their academic background and achievement, qualifications, and skills, which may also be factors influencing the inequality. It is not easy to prove the presence of a causal relationship between an increase in parents’ income and improvement in children’s academic background and achievement.

◆◆◆

One way of examining a causal relationship between parents’ economic situation and children’s academic background and achievement is to look at the impact of an unexpected increase in parents’ incomes on their children’s education. A well-known study conducted in the U.S. state of North Carolina looked at the effects of the twice-yearly redistribution of gambling profits to poor families in casino neighborhoods. The study found that an increase of 4,000 dollars in annual family income led to a rise of around one year in the number of years of education received by children by the age of 21 and also to a decrease of 22% in the probability of becoming complicit in petty crime by the age of 16.

A research paper that summarized the results of seven large-scale experiments conducted in the 1990s to examine the effects of policy assistance on poor families with children offered the conclusion that an increase of 1,000 dollars in annual family income had the effect of improving the level of academic achievement of children at school age by around 0.5-0.6 points in terms of deviation value. In short, a significant number of studies have shown that income redistribution for poor families contributes to the reduction of education gaps among children.

Moreover, a research paper that focused on the mechanism that creates education gaps is also attracting attention. The research estimated the probability of children going on to earn higher income than their parents (the probability of children escaping the generation-to-generation chain of poverty) based on cross referencing residential tax payments and national census data and revealed the presence of significant regional disparities in the probability. In other words, some regions are prone to creating a generation-to-generation chain of poverty, while others are not.

The authors of the paper, including Professor Raj Chetty of Harvard University, attributed the regional disparities to a “neighborhood effect”—i.e., they found that the surrounding community, as well as parents, has a significant impact on children’s education. This may mean that children are influenced by role models in their communities in addition to their parents.

In a subsequent study, Chetty et al. found that among children who relocated during early childhood from a region which was prone to creating a generation-to-generation chain of poverty to a region which was not thanks to governmental assistance, the level of academic achievement and the economic situation improved in adulthood.

Some people may be skeptical of such studies. Is financial affluence really all that matters? Children in poor families may attain a higher level of academic achievement and receive higher education if they are brought up by parents who are enthusiastic about education.

One research paper paid attention to a steep decline in the income of fathers with children in the United States who lost their jobs due to an unforeseen rapid recession and examined how the income loss affected children. The research found that the impact of the fall in parents’ income on children’s university enrollment was insignificant. Parents with reduced income enabled aspiring children to receive higher education by taking on more loans, including scholarship loans. The paper argued that the parents’ mindsets regarding education and their values also play an important role in their children’s education.

◆◆◆

Another important point is that the economic situation is not the only factor that may widen inequality. In addition to financial affluence, the amount of time that parents spent with their children is a contributing factor of the inequality.

There are research papers that examined the effects of the time spent by parents with their children using a “time use survey,” which asks respondents how they spend time in everyday life. All those papers reached the same conclusion: the time spent by parents with their children in early childhood has a very significant impact.

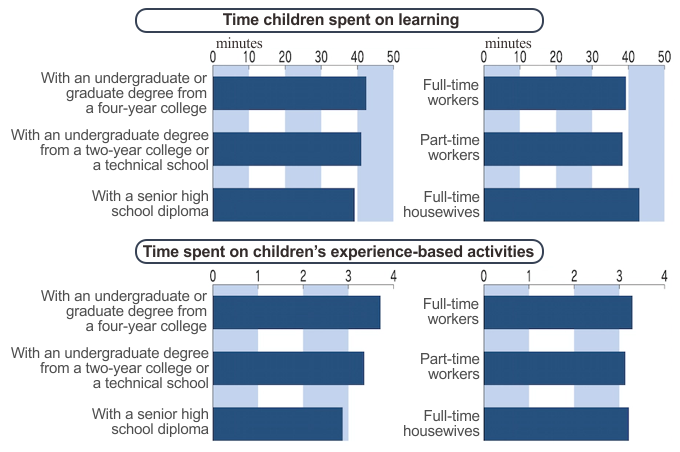

One of those papers, using time usage surveys in 16 Western countries, found a pattern of parental time usage that was common across national borders. In most countries, parents with a higher level of academic achievement tended to spend more time with their children. In the case of mothers in particular, their level of academic achievement had a stronger correlation with the amount of time they spent with their children than whether they are full-time housewives or work outside the home. According to U.K data, the level of education received by parents has a strong correlation with the amount of time spent on children’s “learning,” such as the time spent reading books to children or on helping them do homework. On the other hand, the parents’ level of academic achievement does not have much of a correlation with the time spent on children’s experience-based activities such as visiting museums and engaging in outdoor sports.

According to the Cohort Survey of Children Born in the 21st Century, conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, it is also true in Japan that the higher the mother’s level of academic achievement, the more time spent on children’s learning (see the figure below). However, in cases where mothers work outside the home, the time children spent on learning tends to be shorter.

Source: Prepared by the author based on the Cohort Survey of Children Born in the 21st Century (Children born since 2001).

On the other hand, mothers with a higher level of academic achievement tend to be more enthusiastic about children’s experience-based activities. Also, mothers who work full-time are more enthusiastic about such activities than non-working mothers. As indicated above, in Japan, not only the level of academic achievement but also the working style and the length of working hours may affect the amount of time spent with children, unlike in the United Kingdom.

Multiple published studies indicate that the time that parents spent on their children’s experience-based activities has positive effects on both the cognitive and non-cognitive abilities of those children. This suggests the possibility that reducing the long working hours of parents with children and promoting working style reform may not merely mitigate parents’ burden as workers but also bring benefits to future generations by increasing the time spent with children.

However, inequality in the time spent on children exists, depending on the level of parents’ academic achievement, and parents facing economic hardship find it difficult to spend sufficient time with their children as they struggle to make ends meet. And yet, in most cases, policy measures introduced in order to resolve the inequality in time spent on children have until now failed to achieve significant results.

One study showed results that are useful for considering what kind of assistance is really necessary. It examined the effects of a simple experimental assistance program involving 1,500 parents with second-grade children in Denmark, who were divided into two groups. One group of parents was provided with a leaflet containing tips for improving the quality of the limited time that parents can spend with their children, while the other group was not.

The information contained in the leaflet can be summarized into three key points. The first point is that children’s reading ability can be improved through practice regardless of the present level of ability. The second point is that children should be encouraged to acquire the habit of reading books of their own accord by, for example, asking questions about the books that they have read. The third point is that parents should praise their children for the act of reading itself, rather than for their accuracy or speed when reading or writing.

In the group that was provided with the leaflet, children recorded an increase of 2.6 points in terms of the deviation value regarding the Danish subject three months later, and this positive effect remained seven months later. The positive effect was larger among children whose parents had lower levels of academic achievement and income.

In other words, by helping to improve the quality of time spent by parents with their children, this assistance not only succeeded in raising the overall levels of reading and writing ability among children: it also narrowed the education gap. Studies like this provide important insights for considering what kind of policy assistance can be provided in order to increase the effectiveness of parents’ time usage on their children.

* Translated by RIETI.

August 22, 2022 Nihon Keizai Shimbun