Key Points

- What drives the U.S. is a deep sense of insecurity about national security.

- China is weaponizing supply chains to counter the U.S.

- Japan must lead CPTPP–EU cooperation.

In an August New York Times op-ed titled “Why We Remade the Global Order” U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer declared the advent of the “Turnberry Order,” named after President Donald Trump’s Scottish resort, as the successor to the Bretton Woods system. He described the “Trump Round” as leveraging high tariffs to force bilateral concessions on market access and investment, claiming unprecedented results within months. Yet this amounts less to rebuilding an order than to freeing the U.S. from its constraints.

The Limit of the WTO

Why is the U.S. dismantling the free trade system it once created? USTR argues that China’s failure to reform state-led practices after WTO accession—and indeed their intensification—caused the WTO’s dysfunction.

Why could WTO rules not constrain China? USTR points to the weakness of subsidy notification rules and the inability to capture opaque state supports, as well as the persistent “developing country” flexibilities even after China reached an advanced level of economic development. Since rule changes require consensus, reform proved impossible. The first Trump administration had already concluded that the long-standing assumption—that integration into international regimes would transform rivals into trustworthy partners—was misguided. Supporting China’s WTO entry in 2001 was, in hindsight, a mistake.

Yet the administration’s punitive tariffs backfired, prompting Chinese firms to relocate production to Mexico and Southeast Asia, boosting exports of Chinese intermediate goods and re-exports of finished products to the U.S. Meanwhile, China pulled ahead in EVs and other decarbonization industries, and narrowed the gap in semiconductors, AI, and space—technologies with direct military relevance.

At the same time, U.S. military support for Ukraine revealed critical weaknesses: an eroded industrial base left the U.S. unable to produce sufficient arms. For Greer, existing trade rules became “a suicide pact.” The driving force of Trump’s second administration is not mere protectionism, but deeper insecurity over national security.

Domestic and External Obstacles

Even so, policy execution faces hurdles. First, policy inconsistency. Steep tariffs on steel and aluminum undercut downstream manufacturers’ competitiveness. Crackdowns on illegal employment could tighten labor supply. Without predictability, private investment hesitates.

Tariffs also risk fueling inflation and recession. Legal fragility adds further uncertainty: in late August, the U.S. Court of Appeals upheld a trade authority (ITC) ruling invalidating most reciprocal tariffs imposed under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). While many expect reversal at the Supreme Court, doubts remain.

Even if domestic obstacles are overcome, China looms large. In April, Beijing halted exports of seven medium and heavy rare earths, disrupting U.S. advanced industries—including defense sectors reliant on high-performance magnets, lasers, and ultra-light alloys—and shifting the dynamics of U.S.–China negotiations. Washington rolled back tariff hikes from 125% to 34% and suspended the application of the 24-percentage-point add-on for 90 days, a suspension later extended in August.

China’s export controls on critical minerals—gallium, germanium, graphite—had already begun in 2023. Now, with rare earths, it has found its decisive weapon.

The Weaponization of Supply Chains

This is not a problem confined to the United States. China’s dominance in upstream critical minerals, combined with state-backed growth in downstream decarbonization industries, has given it a powerful lever to eliminate alternative sources of supply. China has largely realized what President Xi Jinping set out in 2020: “to draw international industrial chains toward dependence on China and build strong retaliatory and deterrent capabilities against external disruption.”

In the same speech, Xi insisted that in fields linked to national security, China must establish a self-controlled and reliable domestic production and supply system, capable of sustaining “normal operations under extreme conditions.” This was a clear reference to wartime supply disruption.

Beijing is now completing this weaponization of supply chains at state-driven speed and scale. No single country—including the United States—can counter it alone. Countries seeking to reduce dependence on China must secure alternative supplies through meticulous coordination and public funding robust enough to withstand China’s aggressive price-cutting.

The Trade Order Ahead

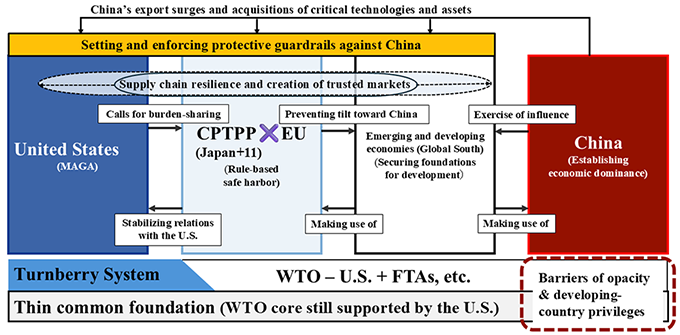

What will become of the global trade order? The diagram below illustrates the transitional landscape under fragmentation.

[Click to enlarge]

The foundation of the WTO will persist but with limited function. Upon it sits a second layer: the United States pursuing the Turnberry Order; the “WTO minus U.S. plus FTA” camp adhering to the rules; and China defending the existing order that favors it while insulating itself behind the above-noted structural barriers to strict rule enforcement.

On top of this rests a third layer of shifting coalitions: For analytical simplicity, this essay groups the actors into four camps: the United States abandoning the WTO; a CPTPP–EU alignment emphasizing high reliability in rule compliance; the Global South of emerging and developing economies; and state-capitalist China.

The CPTPP—led by Japan—and the EU together serve as a safe harbor of rules.

The root cause of the free-trade system’s instability is the rise of actors that exploit it asymmetrically to pursue national enrichment and military buildup, thereby reshaping the world to their advantage. This is not merely an economic issue; it concerns the survival of a free world not subject to surveillance and repression by authoritarian states.

The overwhelming U.S. dominance that underpinned the postwar order has eroded, making cohesion among the United States, Japan, Europe, and Indo-Pacific partners indispensable. Yet with Washington lacking the capacity to attend to its allies, the role of this coalition has become crucial.

Establish fair markets that properly value supply-chain resilience, cybersecurity, and decarbonization, while setting and enforcing protective guardrails against surges of Chinese exports and PRC-linked strategic acquisitions of key technologies and assets. At the same time, stabilizing relations with the United States wherever possible and engaging with the Global South to broaden their options will be essential.

China will seek to neutralize such guardrails. At the same time, its pursuit of CPTPP accession and high-standard FTAs is, at least in part, aimed at putting a brake on moves to reduce dependence on China. How these competing dynamics play out will alter the balance of power and reshape the next order.

Japan’s Role Going Forward

Japan is expected to strengthen economic security seamlessly from peacetime through contingencies and harness it as a driver of growth, thereby enhancing its comprehensive national power. It is also expected to lead coordination between the CPTPP and the EU and help drive the realization of a free and open Indo-Pacific. At the same time, the course of U.S.–China leader-level deal-making warrants close attention. Political stability at home is an urgent imperative.

>> Original text in Japanese

* This modified version was translated by the author.

October 6, 2025 Nihon Keizai Shimbun