In addition to the progress in corporate governance reforms achieved by the Abe administration, shareholder-company dialogue (engagement) aimed at management reform is drawing general attention.

At the same time, the activities of activist funds have begun to stand out. Generally speaking, "activist shareholders" who are involved in corporate management through public channels, such as shareholder proposals and public comments, tend to be the focus of media attention. In practice, however, as with traditional institutional investors, engagement through private dialogue is just as important. Recently, engagement agencies have emerged that principally engage in dialogue that is both private and long-term, which are subcontracted by institutional investors to engage.

Along with analyzing the actual conditions of activist activities since the 2000s in comparison to international conditions, we had the opportunity to obtain the negotiation records from engagement agencies and analyze undisclosed activities. These results are used to examine the actual conditions and future possibilities of activist activities in Japan.

♦ ♦ ♦

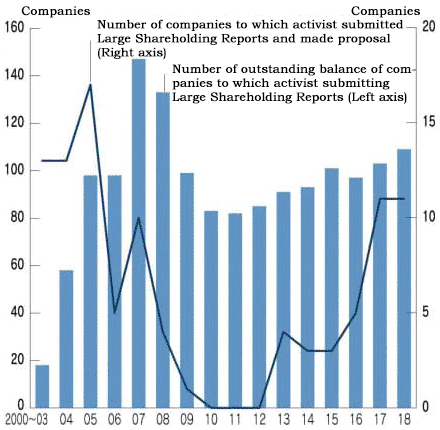

Funds that were confirmed as carrying out public activities in the Japanese market were defined as activist funds. The figure below summarizes the number of companies in which such funds (35 in total) hold 5 percent or more of shares, and organizes the number of confirmed cases of public activist activities.

First, there was an initial peak of activism between 2004 and 2007. From the beginning of the 2000s, focusing on medium-sized companies in traditional industries with abundant cash on hand, activists such as the Murakami Fund began taking action through shareholder proposals. Overseas funds, such as Steel Partners (US) and The Children's Investment Fund (TCI; UK), added momentum to these activities.

This initial peak is characterized by frequent public requests. Of the total outstanding balance of number of large shareholding reports submitted (147 companies at the peak), 63 companies (representing just over 40% of the balance) reported receiving public requests from activists.

Second, many activists requested an increase in shareholder payouts (dividend increases and/or share buybacks) and submitted proposals for going private in anticipation of high-priced buyouts. In contrast, there were remarkably few demands for the appointment of independent directors, or changes in management strategy.

Third, the "probability of success," that is, the probability that the activist requests would actually be implemented by the company, was low. The probability of success was the highest in the United States (60%), followed by Europe (more than 50%), whereas it was only about 20% in Japan.

These activities declined sharply following the global financial crisis of 2008. The balance of number of companies in which activists held 5% or more of listed shares declined to 82 in 2011. There was also a sharp decrease in the number of public proposals, with no such proposals that can be confirmed between 2010 and 2012.

The situation has changed again since the Abe administration embarked on corporate governance reforms. Since 2013, the number of companies where activists hold 5% or more of listed shares has been increasing gradually. Since the revision in 2017 of the "Stewardship Code," which contains the guidelines for the behavior of institutional investors, companies that received proposals have approached the level of the first half of the 2000s. In addition, since 2013, there have been an increasing number of activist funds operating in the Japanese market. While 16 activist funds were recorded prior to the financial crisis, 28 are currently active with new entrants from abroad playing a prominent role.

The characteristics of recent activities are, first, that they are becoming less oppositional. Among the remaining balance of companies to which activist submitted Large Shareholding Reports (109 companies at the peak), activist requests were reported in 37, having decreased to about 30%.

Second, requests have shifted from an increase in shareholder payout to a focus on management, such as the appointment of directors and the sale of unprofitable divisions and assets.

Third, the probability of the success of activism (as described above) accompanied by official requests for activity has not yet reached that of Europe and the United States but has risen to 40%. In addition, the cumulative abnormal return (CAR) when such requests are accepted is about 6%, the same as in the United States and Europe.

♦ ♦ ♦

In the 2010s, some institutional investors established their own engagement departments in their organizations, beginning to conduct engagement themselves, and engagement agencies, as we describe below, also emerged.

Governance for Owners Japan (GOJ) is a pioneering engagement agency engaging with a target company that institutional investors invest on their behalf. In an effort to understand the engagement activities behind closed doors and to compare them with public activism of activist, we obtained the negotiation records of GOJ., Based on the internal records of GOJ, we analyzed the types of discussions that were held with the target companies, the kinds of actions the companies took, and how stock prices changed as a result.

GOJ's engagement has the following characteristics compared to activist activities from the second period.

First, the proposals are often related to corporate governance, such as increasing the number of outside directors, followed by shareholder payout and corporate strategy (strengthening core businesses and improving unprofitable divisions). Second, the probability of success for GOJ improvement requests across proposals related to board structure, shareholder payout, and corporate strategy is very high, at more than 70%. Third, when a company announces policy changes regarding board members and shareholder returns in line with GOJ requests, it has been able to earn a CAR that is roughly the same as that of activists (6%).

The above results suggest that the recent diversification of activism has increased effectiveness compared to the first period.

The success of GOJ activities also suggests that private activism, which is fundamentally carried out behind the scenes, may be effective. It appears that GOJ has gained the understanding of the requests of traditional investors to large companies, appropriately represented them, and tenaciously persuaded them of the merits that the requested action hold for the target company.

Although activists have also been focusing on engagement in the private arena, they have not refrained from public activities when their requests are not met. For example, activists such as Sparx Asset Maangement have primarily adopted a strategy of friendly engagement, but they may also engage in open activities where necessary, as in the case of Sparx with Teikoku Sen-I Co.

The new nature of the Japanese market in recent years features the variety of involvement with corporate management of various types of entities, from public activists to traditional institutional investors. This represents a major difference from the mid-2000s, when activists acted independently from traditional institutional investors.

Finally, let us consider the keys to improving corporate governance in Japan in the future. First, on the corporate side, it is important for management to renew its commitment to dialogue with the increasingly diverse range of institutional investors that are participating in the market. It is important for managers to engage in dialogue with deserving investors who are not ruled by short-term interests, to explain the validity of their strategies through serious dialogue, and to implement necessary reforms.

On the investor side, the focus should be on engagement through collaborative action. The revision of the Stewardship Code in 2017 stated that group engagement through collective action among shareholders may be "beneficial in some cases." However, depending on how information is conveyed, problems related to insider trading regulations may also occur. Furthermore, depending on the content of the engagement, investors may be considered joint owners under the Large Shareholding Reporting System.

In determining the possibilities of collective engagement, an important challenge going forward will be clarifying to what extent specific practices related to these matters are permitted.

* Translated by RIETI.

January 21, 2020 Nihon Keizai Shimbun