With the November 2024 U.S. presidential election decided, Donald Trump is set to return to the presidency. The first Trump administration, dubbed Trump 1.0, imposed additional tariffs of up to 25% on Chinese imports to restore international competitiveness to the United States, exerting significant impact not only on Chinese companies but also on others connected to China through supply chains around the world.

In his campaign promises for re-election (Trump 2.0) he stated that 10-20% tariffs would be imposed on all global imports to the United States, while a 60% tariff would be levied on Chinese imports. If these promises come to pass, what impact will they have on supply chains for Japanese companies and the rest of the world?

Various studies have been conducted over the past few years on the impact of the U.S.-China trade war caused by hikes in U.S. tariffs on Chinese imports in 2018. In this paper, I would like to consider the impact of Trump 2.0 tariff hikes based on these studies including my own.

First, let's reexamine the U.S.-China trade war. Trump 1.0 imposed punitive tariffs on China in July 2018 in retaliation for China’s infringement of intellectual property rights and other reasons. China immediately implemented retaliatory tariffs of the same magnitude. As the United States imposed additional punitive tariffs in August and September, China again responded by implementing retaliatory tariffs. This was the beginning of the tariff escalations, known as the U.S.-China trade war.

Impact of tariff hikes

The U.S. and Chinese tariff hikes was premised on reducing bilateral trade.

In the United States, the decline in imports from China was expected to be covered by an increase in relevant domestic production or relevant imports from third countries. In reality, however, domestic production failed to increase, with little effect seen on labor markets in regions where those products were produced. At the same time, however, employment reportedly decreased in export industries, and particularly the agricultural sector, which were affected by China's retaliatory tariffs.

Imports from allied developing countries such as Vietnam and neighboring countries such as Mexico and Canada increased rapidly; however, imports from Japan did not increase to the same extent.

As detailed data in China have not been published, no comprehensive analysis has been conducted on the impact of the decline in exports to the United States on China's domestic economy.

However, it was observed that the number of newly established businesses decreased in areas related to producing exports to the United States, with job advertisements indicating reductions in both job offers and offered wages. In addition, a decline in nighttime light intensity measured by satellite over China was observed, indicating that China's domestic economy was affected considerably.

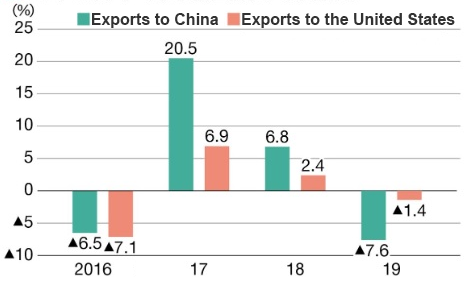

How did the U.S.-China trade war affect Japanese companies? The figure below shows annual changes in Japan's exports to China and the United States. In 2019, changes from the previous year in exports to the United States and China both turned negative, with the decline in exports to China being particularly large. In 2016, about 30% of Japanese companies with overseas production sites had production bases in China, with many Japanese companies having developed close supply chains with China.

Japanese companies that depended heavily on China in terms of production and sales may have been significantly affected by the U.S.-China trade war.

Japan's exports to China

I analyzed the impact of China's sluggish exports on Japan's exports to China by combining the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry's corporate questionnaire data, U.S. tariffs on China, inter-industry relationships based on the input-output table, and a sector-by-sector breakdown of China's exports to the United States. The data demonstrated that about 30% of companies were exporting to China, with more than 10% having production bases in China.

Due to the U.S.-China trade war, the average decline in exports to China by Japanese companies that exported goods to that country as of 2016 was 7.6% in 2019. However, the total decline in sales revenue was limited to 0.9%, which does not represent a significant loss.

Source: Prepared by the author

As for the impact through production bases, declines in exports to China were particularly large for companies that only had overseas production bases in China. The impact was smaller for companies with production sites in multiple foreign countries. No impact was seen for those with production sites in three or more foreign countries. Supply chain diversification seems to have made the difference between the winners and losers.

Next let’s look at how this impacted Japanese companies’ subsidiaries in China? Estimations using data from local subsidiaries indicated a significant decline in exports from those subsidiaries to North America as a direct effect. As of 2016, however, only 1.2% of Japanese companies’ Chinese subsidiaries were exporting products to North America, meaning that the direct impact was not significant.

Nevertheless, for Japanese companies’ local subsidiaries whose customers were Chinese companies that had been exporting products to the United States, a sales decrease was seen as an indirect effect.

The analysis confirmed the following: if Japanese companies had Chinese subsidiaries that depended heavily on sales to Chinese firms with large percentage shares of exports to the United States in downstream industries, the sales in China decreased significantly. On the other hand, exports from such Chinese subsidiaries, particularly to Japan and the rest of Asia, increased to compensate for the losses in China. Such export expansion was especially notable for Japanese companies with three or more overseas production bases, in which supply chain diversification has advanced.

In summary, my analysis found that the adverse impacts of the U.S.-China trade war on Japanese companies and their overseas subsidiaries was more significant for those that were highly dependent on China. However, even among companies with similar dependence on China, those with diversified supply chains were less affected.

Based on the findings of these studies, I would now like to consider the implications of Trump 2.0 for global trade.

Trump 2.0 campaign promises included raising tariffs on Chinese imports to 60%. Since Trump 1.0, countries around the world have been diversifying their supply chains related to China. This trend is likely to accelerate further. Companies with increasingly diversified supply chains will be able to respond quickly and flexibly to the U.S. tariff hike, while those that remain heavily dependent on China will likely face significant negative shocks.

In addition, the Trump 2.0 campaign called for raising tariffs on imports from all other countries by 10-20 percentage points, which could have a cooling effect on exports to the United States from other countries. In response, U.S. domestic employment may recover, but given that the Trump 1.0 tariffs on China failed to lead to an increase in U.S. domestic employment, it is uncertain whether U.S. tariff hikes could resolve the problems of economic disparity and poverty in the United States. The period of turmoil may persist for the foreseeable future.

My study cited in this essay is “Matsuura (2024) Third country effects of U.S.-China trade war: Evidence from Japanese firm-level data, mimeo.” For other references, see https://sites.google.com/site/matsuuratoshiyuki/japanese-top.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

December 7, 2024 Weekly Toyo Keizai