The “job market ice age generation,” who joined the labor force in the mid-1990s through the beginning of the new century, which was a period of extreme job scarcity for new graduates that followed the collapse of economic bubbles, have for many years been at an economic disadvantage because they missed good opportunities for employment during their youth. Since the second half of the 2000s, those people have also come to be referred to as a “lost generation,” and their status as an unfortunate generation has been mentioned over and over again. However, this generation still continues to suffer from their economic disadvantage compared to the people who entered the labor force before the end of the bubble economy era.

The job market ice age generation, who have now entered middle age, is set to face two major problems. One is that low-income workers who have remained single will struggle to get by economically as they lose support from aging parents, and the other is that they will have to make do with inadequate pensions when they themselves reach old age.

◆◆◆

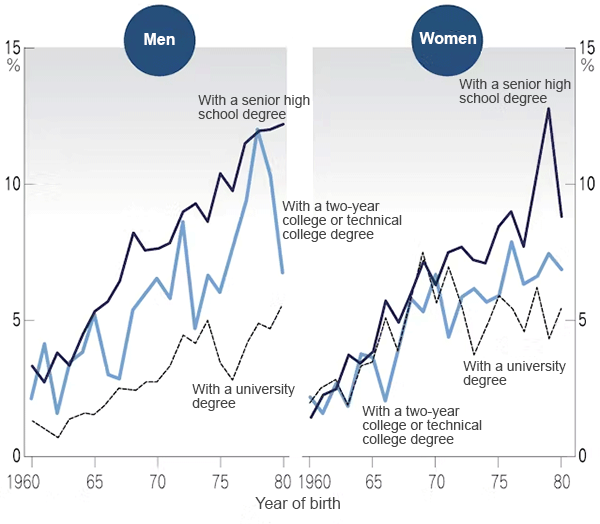

The first problem, the loss of economic support from aging parents, is already becoming apparent. In the figure below, which was compiled on the basis of the Labour Force Survey, the vertical axis represents the percentage of unemployed people and non-regular workers aged 35 to 39 who are single and live with their parents in the population, classified by gender and by educational background, while the horizontal axis represents the year of birth.

In the case of men, across all levels of educational background, the percentage of people who are dependent on parental support is progressively higher among younger generations. Among men who were born in the second half of the 1970s, the percentage is higher than 10% in the group with a high school diploma and around 5% in the group with a university degree. As for women, the percentage is progressively higher among younger generations only in the group with a high school diploma. In the group of women with a two-year college degree, a technical college degree, or a university degree, the percentage remains quite consistent at around 5% among those who were born in the second half of the 1960s or later.

Most people who are now in their later 30s have parents aged between 50 and 70, and they may have been able to make ends meet by living with or sharing meals with parents. However, once they become 40 years or older, the job market ice age generation is expected to face a difficult situation as they can no longer depend on aged parents. In the case of non-regular workers, the working environment tends to be not amenable to their taking nursing care leave. If they are paid by the hour, they lose income in proportion to the working hours reduced in order to care for parents. In short, it will be difficult to amend their lifestyles to allow them to properly care for their parents.

The “baby boomer junior” generation (the children of the baby boomers), who graduated from university in the first half of the job market ice age period already have parents who are old enough to require nursing care. Among people who are younger than the baby boomer junior generation, the percentage of single people whose employment status is unstable and who live with parents is even higher. It is an urgent challenge to develop a system that will enable such workers to properly care for their parents.

The second problem is how to enable the job market ice age generation to prepare for their own old age. If their incomes are low, the amount of savings that they can afford to set aside for old age will be small. Moreover, if they have low incomes during their working years, the amount of pension that they will receive in old age will also be insufficient.

Most regular workers participate in employee pension plans, with insurance premiums automatically deducted from salaries. The longer the duration of membership in an employee pension plan and the higher the premium amount, the greater the amount of pension benefits received in old age. In other words, the effects of the income gap during working age are passed on to the level of pension benefits in old age.

Non-regular workers are unable to participate in employee pension plans in many cases. Until 2016, non-regular workers were not eligible for social security unless their regular weekly working hours were greater than three quarters of a regular worker’s working hours (roughly 30 hours). When employees are covered by social security, their employers are required to share the burden of social security premium payments. Therefore, many companies adjusted working terms in order to exclude non-regular workers from social security coverage.

When workers cannot participate in their employers’ social security plans, they need to join the national health and pension insurance plans on their own. Under the national pension insurance plan, members pay a fixed pension premium that is not linked to the income level, unlike in the case of employee pension plans. Employees participating in the national pension insurance plan alone are eligible to receive only the basic old age pension. Moreover, in the case of the national pension insurance plan, members must themselves undertake the procedures for the premium payments, with no aid from their employers. If there is a period of nonpayment in the payment records, the amount of basic pension benefits will be reduced accordingly.

As the social security coverage for part-time workers has gradually been expanded since 2016, most non-regular workers who are the main earners themselves are allowed to participate in employee pension plans. This marks significant progress. However, workers of the job market ice age generation, who have entered middle age, cannot make up for the loss of pension benefits that they would have received if they had been able to participate in employee pension plans earlier. Besides, the fact remains unchanged that so long as their wages remain low, the amount of pension benefits to be received in the future will be small.

If the pension system remains unchanged when the job market ice age generation reaches old age, the amount of pension benefits paid to them will be inadequate because of the insufficient duration of membership in employee pension plans or the failure to fully pay premiums. In that case, more and more elderly households will find it difficult to make ends meet. At present, more than 50% of the beneficiaries of the public assistance program (income subsidy for needy families) are people aged 65 or older, and the percentage may rise further in the future.

◆◆◆

The framework of the government’s support for the job market ice age generation is comprised of three pillars: employment support provided through Hello Work public employment assistance offices, support for the jobless provided through “local youth support stations,” and consulting support provided by various organizations for people suffering from personal problems such as social withdrawal. This framework is an extension of the system that was created in the 2000s to help young people achieve financial independence.

Of course, regardless of generation, it is necessary to continue the various support measures already introduced, to provide opportunities to develop skills, and to promote non-regular workers to regular workers. However, the job market ice age generation in their middle age cannot make up for their loss of working experience during youth. The time has come to accept the fact that the various measures implemented in the past two decades have not succeeded in helping the job market ice age generation attain employment stability and to consider the specifics of expanding welfare benefits.

Under the existing social security framework, wealth redistribution for people who are working but whose income is inadequate is insufficient. The public assistance program is the only public support available for people who do not qualify for old-age benefits or disability benefits. In many cases, if non-regular workers become unemployed, they cannot receive sufficient unemployment benefits under the employment insurance system. The public safety net provides only tenuous support to working-age people who have income or assets in an amount that barely misses the eligibility threshold for the public assistance program. Those problems were already pointed out when the phrase “working poor” became popular in the 2000s, but few corrective actions have been taken in the past two decades.

Benefits paid from employment insurance and other programs that constitute the social security safety net are available only for people who have paid insurance premiums, so this safety net does not provide relief for people whose employment status has been unstable since their youth. On the other hand, the eligibility criteria for the public assistance program are very strict, and it is not easy to regain economic independence once struggling people have come under that protection. It is essential to provide relief before their situation becomes so difficult that they need to qualify for the public assistance program.

Regarding working-age generations, it is desirable to provide support to those who are working but who are unable to earn sufficient income in ways that increase income without dampening their motivation to work. For example, a negative income tax (refundable tax credit) introduced in some Western countries and discussed as a possible option in Japan in the past, provides benefits to people whose income is below a certain threshold in proportion to labor income. Negative income tax is not necessarily an optimal form of support, but in-depth discussions should be held based on ideas that are not constrained by the existing framework of support.

As society ages further and as more and more people remain unmarried throughout their lives, the number of single people that face the issue of how to reconcile working with caring for parents will continue to increase in the future. Going forward, enhancing nursing care services and increasing nursing care insurance benefits for low-income households will be important safety net measures to prevent the further erosion of the income of single people with an unstable employment status due to the need to care for parents, including generations that are younger than the job market ice age generation.

Discussions on pensions are becoming brisk in the runup to the revision of the pension insurance laws scheduled for 2025. While there are various points of debate, including concerns over pension funding due to the demographic crisis and whether or not to abolish the Category III insured person designation, it is high time that discussions started on the specifics of the low pension problem faced by the ice age generation.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

May 10, 2024 Nihon Keizai Shimbun