Tax reform attracts a lot of public attention. Raising the tax threshold for annual income and consumption tax cuts have become major issues in the recent Japanese election campaigns. The 2010s saw corporate tax cuts in Japan. Corporate income is subject to not only national corporate tax but also local corporate inhabitant tax and local corporate enterprise tax. The statutory effective tax rate (ETR) that combines these three taxes was reduced from 39.54% to 29.74% for large companies (capitalized at more than JPY 100 million) and from 40.87% to 33.59% for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (capitalized at JPY 100 million or less) between FY2011 and FY2018.

In particular, the reforms from FY2014 implemented by the Shinzo Abe administration reduced the statutory ETR, but increased the pro forma standard tax for large companies to secure tax revenues. Pro forma standard taxation is based on value-added components, including labor costs and capital, in the form of the local corporate enterprise tax. Large companies capitalized at more than JPY 100 million are subject to the tax.

Corporate tax places a heavier burden on more profitable companies. On the other hand, pro forma standard taxation spreads the tax burden more broadly but thinly across a wider range of companies, including those without earnings. The government called this reform “growth-oriented corporate tax reform,” aimed at improving the profitability of companies. Since the reform, however, capital investment and wage growth have been slower than the increase in reserves, cash, and deposits, raising doubts about the effectiveness of the reform.

Measuring the effects of reform

Have the reduction of the tax rate and the expansion of the tax base through the pro forma standard tax increase under the growth-oriented corporate tax reform achieved their intended objectives? In particular, has the lighter tax burden on companies resulted in their expanded investment and employment?

In the first place, it is difficult to measure the effect of any corporate tax reform. Changes in corporate investment and employment that occur after a reform could be a result of changes in economic conditions and industrial structures. Therefore, even the failure of a corporate tax reform to increase investment and employment does not necessarily indicate failure of the reform.

Calculating the actual tax burden for each company is also challenging. The tax reform between FY2014 to FY2018 included a reduction of the tax rate and the expansion of the pro forma standard tax, meaning that the tax burden on all companies was not necessarily reduced in proportion to the rates cut.

One method of calculating the tax burden is by dividing taxes paid by profits earned. However, the tax burden calculated this way reflects past investments and behaviors, so it is not necessarily an appropriate indicator of the impact of tax reform on investment and employment. If a company behaved rationally, they would focus on future tax burdens rather than past ones.

Therefore, we used the “tax rate on profits generated by new investment projects” as an indicator of the tax burden. This involves projecting the tax that would be paid on profits from hypothetical investment projects, and is referred to as the “forward-looking effective tax rate.” This tax rate varies from company to company because it is affected not only by the statutory tax rate but also by depreciation rules and investment financing methods.

We used company-level data to analyze what kind of companies were greatly affected by the growth-oriented corporate tax reform that was implemented from FY2014 and how investment and employment were affected by the reform.

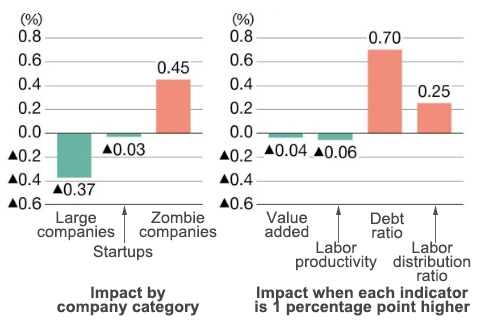

The figure below shows the impact of the growth-oriented corporate tax reform between FY2014 and FY2018 on the forward-looking ETR:

(Source) Prepared by the authors

For example, minus 0.37% for large companies indicates that the ETR tends to be about 0.37 percentage points lower than for SMEs. The ETR for zombie companies (with operating profit margins of less than 2% and debt ratios of more than 70%) tends to be 0.45 points higher. When the debt ratio is 1 point higher, the ETR is 0.70 points higher. When the labor distribution ratio is 1 point higher, the ETR is 0.25 points higher.

In other words, in general, large and highly profitable companies see reduced tax burdens, whereas companies with large debts and high labor distribution ratios have higher burdens. The reforms have tended to level out tax burden rates, indicating that the reforms achieved the objectives of allowing companies to share the tax burden broadly and thinly and lowering the tax burden on companies with higher earning power.

The impact on corporate behavior

The most important aspect of corporate tax reform is arguably its impact on corporate behavior. Our analysis confirmed that companies with large tax cuts tend to increase capital investment and employment. This means that the growth-oriented corporate tax reform has had a certain effectiveness. However, the magnitude of the effect differs between SMEs and large companies, with the tax cut having a greater effect on SMEs in terms of increasing capital investment and employment.

Why does the effect differ between SMEs and large companies? Our analysis suggests that different results from the content of specific reform measures. While SMEs capitalized at JPY 100 million or less receive smaller tax cuts, they remain free from the pro forma standard tax that was subjected to the tax base expansion.

For large companies, a larger cut in the ETR on profits coincided with an increase in the pro forma standard tax. This means that the larger ETR cut for large companies has been partially offset by the expansion of the pro forma standard tax. This may be one of the reasons why the impact of the tax reform on investment and employment at large companies seems smaller than indicated by the ETR cut.

The pro forma standard tax also applies to labor cost and rent for land and buildings, so the extent to which the ETR cut increased capital investment and employment for large companies might have been reduced by the pro forma standard tax expansion. And given that wage hikes have been a significant challenge for the Japanese economy in recent years, the pro forma standard tax expansion under the corporate tax reform might have discouraged companies from raising wages.

(For the reference documents for this article, see Kobayashi, Bamba, and Sato (2025), “The Impact of Corporate Tax Reform on Firm Dynamics: An Empirical Study of the Shift from Income-Based to Pro Forma Standard Taxation in Japan.” RIETI DP, Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry)

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

July 12, 2025 Weekly Toyo Keizai