In September 2021, Taiwan and China successively submitted applications to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP or TPP11). The TPP framework was originally intended to contain China and to pave the way for the Free Trade Area of the Asia Pacific (FTAAP) led by the United States, but the character of the framework changed significantly when it was revived as the CPTPP with Chinese official application for accession in 2021 after the US withdrawal in 2017. In Japan, there is no end to calls for the return of the United States from political and business circles, who are apprehensive about the situation.

However, with the 2022 midterm elections around the corner, the hurdles are high for the Biden administration, which professes a worker-centered trade policy, since a return to the TPP framework would bring competition with imports and open up the market to the Asia Pacific countries. In addition, Jen Psaki, White House Press Secretary, says that engagement in the region would be about more than trade and commerce. Ota Yasuhiko, Senior Staff Writer at The Nikkei, alludes to the technology principles adopted at the Second Japan-Australia-India-US (Quad) Summit Meeting on September 24 when he says that the United States is losing interest in the CPTPP and intends to form a new trade order that fences in semiconductor supply chains and other advanced technologies developed in the ASEAN and Taiwan, which are situated within the diamond shape that connects the Quad countries (October 18, The Nikkei). The Pittsburgh Statement of the US-EU Trade and Technology Council (TCC) on September 30 also suggests that the United States is pivoting away from its traditional trade and investment agreements to a framework for technology cooperation and an economic order based on security and value-oriented diplomacy.

The US position was made even clearer in a TV Tokyo interview with Gina Raimondo, US Secretary of Commerce, on November 15. The Secretary said that the United States will not return to TPP12 for the time being, and clarified the US policy of engaging in the Indo-Pacific region through a more powerful new economic framework with the focus on digital trade, semiconductors, and cleaner energy.

Assuming that the United States is not planning to return any time soon, it falls to Japan as the largest economy in the CPTPP to manage negotiations for the accession of China and Taiwan. How should Japan deal with the situation?

Consider China/Taiwan Accession from the Viewpoint of the FTAAP

The initial issue confronting the CPTPP is whether negotiations to admit China should start or not. Recently, the ruling party in Japan has been consistently cautious or negative about accession for China. However, the bottom line is that Japan should not turn China away at the gate. As discussed below, this would not be consistent with the FTAAP initiative where Japan is also committed.

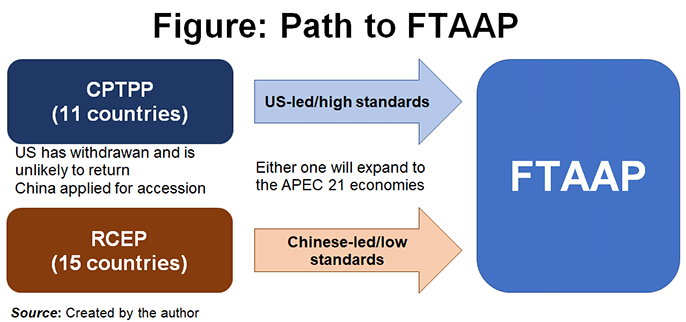

The FTAAP is a mega-FTA consisting of the twenty-one economies of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC). It was first formally recognized as an APEC policy agenda in the Yokohama Vision, the APEC Leaders Declaration after the 2010 Yokohama Summit meeting chaired by Japan. According to the declaration, the intention was to implement the FTAAP based on the development of the TPP and the ASEAN+6 (subsequently, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement, RCEP), which were under negotiation at the time. This meant that the US-led TPP and the Chinese-led RCEP would compete with each other for implementation of the FTAAP. The guiding principles for the FTAAP were not changed in the APEC Putrajaya Vision 2040, which retains the Bogor Goals of free and open trade and investment by 2020.

Both China and Taiwan are members of the APEC 21 economies. Therefore, excluding China from the CPTPP means that the route to FTAAP through the CPTPP is abandoned in favor of the route via the RCEP. However, according to "Pathways to FTAAP" adopted together with the Yokohama Vision, "FTAAP should do more than achieve liberalization in its narrow sense; it should be comprehensive, high quality and incorporate and address ‘next generation’ trade and investment issues." The RCEP lacks rules on labor and the environment, which are included in these "‘next generation’ trade and investment issues" (NGeTI), and does not have any provisions for the market access of government procurement. In that sense, it is only possible to implement a high-level FTAAP that includes the NGeTI via the CPTPP. It is also inevitable that China will join the CPTPP at some point in time.

Since the RCEP will take effect at the start of 2022, implementing the FTAAP via the RCEP seems the more realistic option right now unlike the situation in 2015 when the TPP was ahead and the RCEP was lagging behind. If China's application for accession to CPTPP is refused, the country may make use of this RCEP option to gain an edge in the initiative to form the FTAAP. It would be the same situation as when China submitted an application to join the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) on November 2 to pre-empt the Indo-Pacific digital trade agreement initiative that the Biden administration is considering. To keep the situation under check, it is necessary to strategically confront China's membership application for CPTPP and to stick to the path of implementing the FTAAP via the CPTPP even if the United States is not a contracting party to the agreement at present.

Turning China away would also undermine the strong logic for supporting Taiwan's accession. In short, the logic that China should not be excluded from the CPTPP, which is a milestone toward the FTAAP vision, means that Taiwan, which is one of the APEC 21 economies, must also not be excluded. By this logic, China's exclusion of Taiwan must be rolled back, but excluding China is contradictory.

The CPTPP Must Not Be Allowed to Turn into the RECP

But this does not mean that China can be permitted to join under any conditions. The above-mentioned "Pathways to FTAAP" advocates for "comprehensive, high quality" rules. Therefore, if the expansion and development of the CPTPP to reach the FTAAP is the cause that opens the door to China, it is essential that China meets the CPTPP conditions for accession without any compromise.

On this point, the benchmarks adopted by the TPP Commission in 2019 demand that aspirant economies must demonstrate the "means by which they will comply with all of the existing rules contained in the CPTPP" and must "undertake to deliver the highest standard of market access offers on goods, services, investment, financial services, government procurement […] These must deliver commercially‐meaningful market access for each Party …." These high-level benchmarks are also confirmed in the Joint Ministerial Statements of the TPP Commission in June and August 2021 at the start of the process for admitting the United Kingdom. In short, there is no path of accession open to China other than to commit to all CPTPP rules and to offer maximum market liberalization.

On the other hand, Henry Gao, Associate Professor at Singapore Management University, among others, argues that entry for China would be easier than expected if exceptions to the CPTPP public policies and national security are used ("China's entry to CPTTP trade pact is closer than you think," Nikkei Asia, September 20, 2021). If China holds out hopes for accession based on such optimism, one must question the perspective on their interpretation of exceptions.

With regard to the true state of economic reform, Gao and others claim that market distortion by state-owned enterprises has been eliminated due to compliance with the strict conditions for entry to the WTO. However, the WTO Trade Policy Review: China published in October 2021 pours cold water on such optimism by pointing out that China still maintains several and substantial industrial subsidies, that it has failed to report this to the WTO, that state-owned enterprises have a major presence even in non-strategic sectors, and that privatization is not making progress.

In his recent book The Long Game (Oxford University Press, 2021), Rush Doshi, Director for China on the National Security Council, argues that China has developed a grand strategy for rewriting the US-centered international order in the long term. My research (China and CPTPP, Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry, RIETI) also suggests that the aim of China's application to join the CPTPP is to gain institutional discourse power and to rewrite the economic order in Asia and Oceania.

If, in China's view, rewriting this economic order means to lower the CPTPP rules to a level that is more acceptable to China, i.e., to turn the CPTPP into the RCEP, this must never be allowed.

Enhance Compliance Monitoring Systems Premised on US Absence

If the CPTPP is supported and developed into the future FTAAP, it will need a structure that will function autonomously to some degree regardless of the United States' course of action. As proposed separately ("Maintaining High-Level Rules Should Be the Basis for Allowing Chinese Accession to the CPTPP," Keizai kyoshitsu column, November 4, The Nikkei), I would recommend four policies: (1) Swift implementation of accession for the United Kingdom and establishment of a system of cooperation with Australia, Canada and other countries sharing a common belief in rule of law; (2) Cooperation with the United States; (3) Reinforcement of the CPTPP compliance monitoring system; and (4) medium and long-term collaboration with the EU.

With regard to point (3), in particular, the current CPTPP compliance monitoring system is far from perfect. When the TPP12 was agreed in 2015, the premise was to rely on the United States for monitoring and compliance. However, the effectiveness of autonomous compliance monitoring for the CPTPP must be guaranteed in a situation where the United States is absent.

To start with, if a comprehensive trade agreement like the CPTPP is managed multilaterally by eleven countries with large trade volumes, management will be difficult without a permanent forum for discussion and a supporting secretariat. For the CPTPP, in particular, duties and mandates of the subcommittees set up for each chapter are provided in detail. To make sure they function effectively, the secretariat function is essential. In fact, setting up a secretariat is clearly stated in the provisions for the RCEP, which is a similar mega-FTA.

Another challenge is to strengthen the procedures for dispute settlement. Where Chapter 28 (Dispute Settlement) is concerned, CPTPP runs the risk of confusion over the nomination of a panel chair and panel decisions are not binding. As I mentioned earlier, there are concerns that China aims to evade the strict CPTPP rules by abusing the exception clauses, but this can to some degree be prevented with an effective dispute settlement system. In disputes over the security exception under the WTO or Investor-State-Dispute Settlement (ISDS) arbitration, the prevailing approach is to determine whether the country in question has invoked the exception in good faith or not. This can also be applied to the CPTPP cases.

Support Accession for Taiwan and the Return of the United States

As seen earlier, Japan's ruling party supports accession for Taiwan. Seeing that Taiwan is an important partner in East Asia that shares the values of the rule of law and democracy, this is a given. However, amid fierce opposition from China under the One-China policy, how to provide support is a challenge. At the risk of sounding somewhat outlandish, I would like to propose a consideration of the following possibilities.

Firstly, both China and Taiwan must be made to promise not to interfere with the consensus-building to start the accession process for both economies. Earlier I said that accession by China and Taiwan is a given once the CPTPP evolves into the FTAAP. If so, we must adhere to the principle that China as an independent country and Taiwan as a separate customs territory are both eligible to join the CPTPP according to the rules for accession. By agreeing to accession by Taiwan, China would at the very least not contradict the One-China policy.

Secondly, if we try to maintain a neutral stance on the One-China policy, simultaneous entry by China and Taiwan should be the condition for starting the accession process as was the case with WTO membership in 2001.

On the other hand, if, for argument's sake, the purpose of China's accession application is to deprive Taiwan of international space, China may employ underhanded means to endlessly delay the process of simultaneous accession by China and Taiwan. Consequently, my third point is that provisional accession must be recognized when either China or Taiwan have met the conditions for accession. For example, methods such as no formal recognition of membership and no permission to participate in the TPP Commission even though market access and rules have been fully applied, or investment of only observer status without voting rights. Consequently, even if one party has provisional access before the other, it will not participate in the consensus to approve the other party's accession.

Such proposals may be criticized as naive. For example, Professor Kawashima Fujio at Kobe University says that China will never recognize accession by Taiwan to the CPTPP under the Tsai Ing-wen administration, which does not accept the 1992 Consensus that is the premise for the One-China principle in both China and Taiwan (Prof. Kawashima's blog, September 30, 2021). However, if Japan, in the face of political reality, compromises the basic stance that it will continue to serve "as a standard-bearer for free trade and work to expand economic zones based on free and fair rules to the world" (Policy Speech to the 200th Session of the Diet by then Prime Minister Abe Shinzo on October 4, 2019), and panders to China, for certain a meaningful China-Taiwan accession linked to the FTAAP will not be realized.

With regard to the United States, there must be institutional guarantees that a return to the TPP framework will not be undermined even if it comes after accession by China. For example, one proposal might be that the TPP12 signatories proceed with ratification in advance so that the treaty can take effect as soon as possible after the return of the United States. If, for argument's sake, China, which is not a party to TPP12, were to join the CPTPP, China would not have the right to veto the return of the United States to the TPP12 since the CPTPP and TPP12 are legally separate agreements. Since the rules for both agreements are nearly identical, the United Kingdom and other new member countries could accede the TPP12 relatively easily via market access negotiations with the United States. If China does not faithfully comply with the CPTPP, the other signatory nations would have the option of a full-scale shift to the TPP12 once it takes effect.

The CPTPP currently in force does not specify what will happen when the TPP12 takes effect, but only provides for a review of its operations by the parties to the treaty. On this point, it is necessary to scrutinize the institutional design, including the above-mentioned proposals, in advance so that it does not close off the possibility of a US return.

In his recent book China and the WTO (Princeton University Press, 2021), Professor Petros C. Mavroidis at Columbia University, an authority on WTO legal research, has argued that the international community must confront trade distortions due to state capitalism by formulating new multilateral rules without excluding China. He says that the frame of mind needed is to "Be inclusive and prudent" and to "Be bold and realistic." This suggestion also applies to the CPTPP. Now, China wishes to accede to a CPTPP that was originally designed as a tool to contain it, and the creator of the tool, i.e. the United States, is absent. We need to confront this somewhat comical situation not by just following precedent, but with bold and creative thinking. Today when there is no direct support by the United States within the CPTPP framework, Japan's self-appointed leadership as a standard-bearer for free trade will be tested.

Translated from "Chugoku/Taiwan no CPTPP kanyushinsei to Nihon no taio (China and Taiwan's Applications to Join the CPTPP and Japan's Response)," Gaiko (Diplomacy), Vol. 70 Nov./Dec. 2021, pp. 66-71. (Courtesy of Toshi Shuppan). This English version first appeared on Discuss Japan. Reproduced with permission.

February 8, 2022 Discuss Japan