The second Trump administration, known as Trump 2.0, will be inaugurated in the United States in January 2025. Trump, a self-proclaimed “tariff man,” has already threatened to impose an additional 10% tariff on nearly all imports from China and a 25% tariff on imports from Canada and Mexico. This represents the suspension of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), a free trade agreement.

President Trump planned to withdraw the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement during his campaigns towards his first inauguration in 2017 and implemented the plan. It is quite possible that the tariff policy that he has advocated will be implemented immediately after his inauguration.

◆◆◆

It is useful to review the effects of Trump 1.0 policies when predicting the impact of Trump 2.0 trade policies on both global and Japanese trade. Trump 1.0 imposed an additional 25% tariff on a wide range of Chinese imports, from vehicles to steel products.

It is well-known in international economics that if a large country, such as the United States, imposes tariffs on imports, the exporting countries’ FOB (free on board) prices can be expected to decline, improving the large country’s terms of trade (relative prices of the large country’s export goods compared to import goods). If so, the Trump 1.0 tariff policy on China should have benefited the United States from the improvement of the terms of trade.

According to multiple analyses by U.S. researchers, however, little decline was seen in FOB prices for imports from China that were subject to additional tariffs. This means that the measures failed to improve the terms of trade for the United States.

A study by Professor Tadashi Ito (Gakushuin University) found that, while imports of goods from China subject to tariff hikes decreased significantly, imports of such goods from Mexico, Vietnam, India, and other countries increased, which implies a so-called trade diversion effect.

Interestingly, China’s exports of goods subject to the U.S. tariff hikes to countries other than the United States increased more than their exports to the United States decreased, resulting in an increase in China’s overall exports of the goods in question.

These studies suggest that the Trump 1.0 tariff policy might have failed to produce the intended results.

How was Japan’s trade affected under Trump 1.0? In this regard, I conducted collaborative research with Professor Keiko Ito (Chiba University), Professors Masahiro Endoh, Toshihiro Ohkubo, Toshiyuki Matsuura, and Akira Sasahara (Keio University) to analyze import and export declaration data between 2014 and 2020.

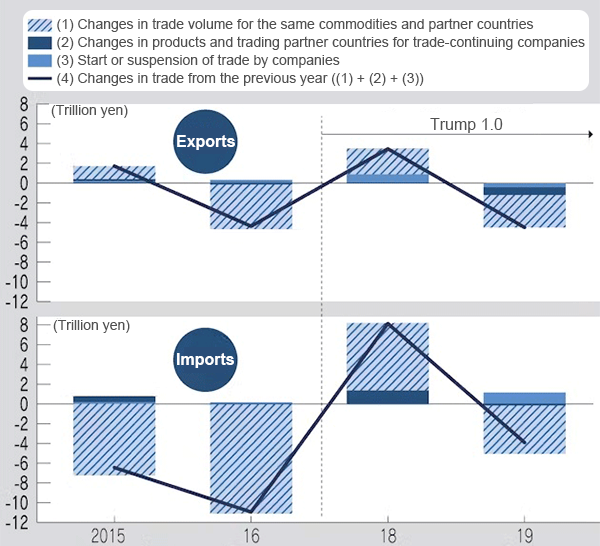

Let’s review changes in Japan’s imports and exports before and after the Trump 1.0 inauguration along with a factor-by-factor breakdown of the changes (see the chart). Although it is difficult to identify any trend in annual changes in trade, the decrease in exports between 2017 and 2019 under Trump 1.0 was slower than in the 2014-2016 period before the Trump 1.0 inauguration, but there was a decrease in imports in the two-year period before the inauguration which turned upward in the next two years.

There are three main factors that contribute to changes in trade volume. In the case of exports, the first factor (1) is the change in the amount when the same firms export the same products to the same countries. Such change is referred to as the intensive margin. The second factor is (2) changes when the same exporting firms change products for export and destination countries and the third factor (3) is when firms start or suspend exports. This is referred to as the extensive margin.

The intensive margin tends to account for an overwhelming share of changes in imports or exports. U.S. studies attribute this tendency to the fact that a small number of large firms account for most exports and imports.

This type of oligopolization is observed in Japan’s external trade, indicating that this also applies to Japan. In other words, changes in trade volume by a few large firms in specific products with specific countries exert a great influence on Japan’s total external trade.

Moreover, as these firms engage in both imports and exports, a decrease in these firms’ exports of consumer goods leads to a decline in their imports of raw materials and intermediate goods. Regarding the intensive margin that accounts for an overwhelming share of Japan’s external trade, no accelerated decrease in trade or other negative effect was seen after the Trump 1.0 inauguration.

As shown in the chart, the impact of changes by trade-continuing firms in products and trading partner countries accounted for about 17% of the decline in exports in 2019. Although Japanese firms may have changed export destinations and products in response to hikes in U.S. tariffs on China in the year, such changes should have exerted a far smaller impact on Japan’s external trade than the intensive margin. Therefore, the trade data do not suggest that Trump 1.0 trade policy had a significant negative impact on Japan’s trade.

◆◆◆

So, how will the world and Japan be affected by the expected additional Trump 2.0 tariffs?

According to a simulation result by the economist group of the Institute of Developing Economies, JETRO, if Trump were to impose a 60% tariff on China and a 20% tariff on all other foreign countries from January 2025 as explicitly stated during his presidential election campaign, the United States itself would be hit the hardest economically as of 2027.

U.S. Gross domestic product (GDP) would be 2.7% lower than in the case without the additional tariffs, with automotive and services industries hit hardest. China’s GDP would be 0.9% lower, indicating that the United States would be hit harder than China.

On the other hand, Japan and other countries would see their benefits from the U.S.-China trade war offset by the direct negative impact of the additional tariffs, so the overall impact would be mild. Global GDP would decline by 0.8%, with almost all industries affected.

Along with tariffs, the impact on trade through exchange rate fluctuations is attracting attention. There has been much discussion on the impact of Trump’s policies on the Japanese yen.

According to an analysis that I conducted in cooperation with Professors Keiko Ito Toshiyuki Matsuura, and Dr. Uraku Yoshimoto of the Policy Research Institute, Ministry of Finance, yen exchange rate fluctuations in recent years have had little effect on dollar-denominated export values. The reason for this is that contracts denominated in foreign currencies account for more than 60% of Japan’s export transactions. As a result, exchange rate fluctuations do not change export prices in foreign currencies.

Furthermore, the response of export volume to exchange rate fluctuations has been weak. This is related to the fact that major manufacturing firms in Japan, as active importers and exporters of goods within international supply chains, have already made efforts to avoid exchange rate risks. Even with significant yen exchange rate fluctuations due to Trump 2.0 policies, Japan’s trade volume is expected to remain almost unaffected.

Given the abovementioned findings, it is anticipated that the additional tariffs under Trump 2.0, while reducing China’s exports to the United States, are likely produce a trade diversion effect that will result in an increase in imports into the United States from countries subject to lower tariffs. It is also highly likely that the increased burden of the tariffs will most heavily affect American citizens.

For Japan, the best course of action is to steadily implement policies that meet its national interests from a longer-term perspective without being swayed by inconsistencies in Trump’s remarks. Specifically, Japan should correct the oligopolistic trade structure by providing support for new entrants in trade, maintain the free trade system through the expansion of the TPP, which has developed into the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), and promote foreign investment in Japan to revitalize the domestic economy.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

December 25, 2024 Nihon Keizai Shimbun