The digitalization of the economy has triggered increases in the use of electronic order placing and receiving, and online downloading and distribution. Trade in goods and services involving the collection and transfer of data at the time of electronic order placement and delivery is known as “digital trade.”

For example, the use of delivery services and music and video distribution services provided by foreign firms is in effect a digital form of import. In the case of inter-firm transactions, examples of digital trade include placing orders for parts and maintenance services through internet ordering systems of suppliers (such as parts manufacturers) and outsourcing ICT-related development and maintenance work to foreign contractors.

From the perspective of digital trade, Japan depends heavily on foreign supply chains. In such sectors as ICT and digital products and services, Japan has a significant import excess (trade deficit). According to the 2022 edition of the White Paper on Information and Communications in Japan, prepared by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Japan’s goods and services trade in the ICT sector comprised 10.6 trillion yen in exports and 16.8 trillion yen in imports in 2020.

According to statistics on international trade in digitally deliverable services prepared by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, in 2021, Japan recorded an import excess of 30 billion dollars, representing the largest trade deficit among the G20 countries and regions. On the other hand, large trade surpluses were recorded by such countries as the United States (260 billion dollars), the United Kingdom (180 billion dollars), India (97 billion dollars), and China (30 billion dollars).

Those trade figures reflect Japan’s low level of competitiveness in the digital sector. To correct Japan’s trade deficit and develop stable supply chains, it is necessary to take prompt action to promote digital transformation (DX) in the country.

As for Japan’s dependence on foreign supply chains, information security has become a particular matter of contention in the case of outsourcing business processes (services import) to China and other East Asian countries. In 2021, it came to light that personal information handled by LINE, a messaging service provider, was accessible by employees of the Chinese firm that was the outsourcing contractor, and as a result, LINE decided to terminate the outsourcing arrangement and fully bring relevant business processes to Japan.

While transferring business processes outsourced to foreign contractors back to Japan may be essential on information security grounds such as protecting personal information, outsourcing firms could suffer a decline in their competitiveness due to increased cost. Japan must fundamentally strengthen its competitiveness in the digital sector, with an eye to promoting exports, by promoting DX while enhancing information security measures.

◆◆◆

What is important for promoting digital export? As a general rule, regarding goods export, firms’ export competitiveness depends on their level of productivity under the “new” new trade theory, which has been advocated mainly by Professor Marc Melitz of Harvard University. Indeed, it has been found that exporters have higher productivity than non-exporters.

Does that principle also apply to digital trade? I conducted a survey of around 4,000 Japanese firms on whether or not they are collecting digital data, an activity closely related to digital trade, with Professor Eiichi Tomiura and Associate Professor Byeongwoo Kang, both of Hitotsubashi University.

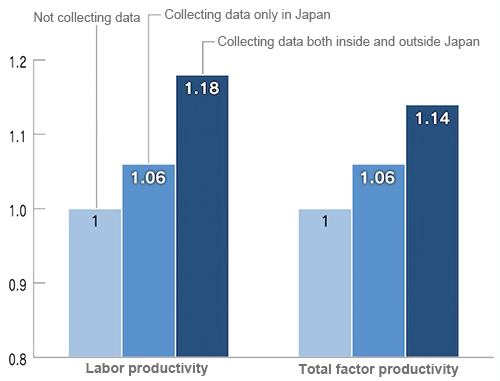

We found that firms that routinely collect data for business purposes both inside and outside Japan (there were a total of 443 such firms) had a high level of productivity relative to firms that collect data only inside Japan (there were a total of 691 such firms), while firms that neither collect data inside or outside Japan (there were a total of 2,891 such firms) had the lowest level of productivity (see the figure below). The relative levels of productivity among those three categories of firms remained unchanged even after controlling for factors such as the presence or absence of export activity and foreign direct investment and industrial attributes.

Source: Prepared by the author based on “Characteristics of Firms Transmitting Data Across Borders: Evidence from Japanese Firm-level Data” (2020), written by Tomiura, Ito, and Kang.

Our findings reflect the presence of fixed costs related to data collection. Adapting to foreign regulations on data transfer and installing servers and developing networks entails additional fixed costs. Presumably, having a sufficiently high level of productivity to cover such fixed costs is the threshold for collecting cross-border data and participating in digital trade. Promoting free data flows, which lowers the hurdle for export, increases the profitability of digital export, thereby encouraging more and more firms to start such trade.

The expansion of digital trade is expected to raise the levels of domestic wages and productivity. This benefit of digital trade, which can be explained by the abovementioned “new” new trade theory, is brought about mainly through the labor market. An increase in exporters will expand labor demand, leading to a wage increase. As a result of the wage increase, low-productivity firms will be driven out of the market while high-productivity ones remain. The average level of productivity on an industry-wide basis will rise due to the reallocation effect, which refers to the transfer of market shares from low-productivity firms to high-productivity ones. Indeed, in Canada and Chile, productivity rose markedly because of the reallocation effect following trade liberalization.

If this mechanism applies to digital trade as well, the liberalization of cross-border data transfer is expected to encourage more firms to engage in exporting activity, leading to rising productivity through the reallocation effect generated by an increase in demand for workers with digital skills and a wage increase. On the other hand, the reallocation effect could create losers, resulting in job losses as firms are driven out of the market. In terms of policy planning, it is important to smoothly shift workers thus made redundant to high-productivity firms, and the key to doing that is reskilling.

◆◆◆

Many challenges stand in the way of achieving a rise in productivity by expanding digital exports from Japan, three of which are pointed out below.

The first challenge is how the free data flow initiative will play out. Under the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF), a U.S.-led initiative to create a new economic area, India, which is leaning towards data localization, refrained from participating in trade negotiations at a ministerial conference held last September. Negotiations may stall even among partner countries due to differences in the approaches to digital trade. Japan may be able to curb the rise of digital protectionism by sharing its abundance of knowledge and data regarding the aging of society and post-disaster reconstruction with countries that are planning to strengthen regulations on data transfer.

The second challenge is a lack of workers with digital skills in Japan. According to a survey conducted by the Institute for Information and Communications Policy under the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, when asked which personnel are in charge of data analysis, around 70% of the respondent firms replied that personnel who were not specialized in data analysis at relevant business divisions were in charge. According to the most recent survey conducted by the institute, there is no difference in that respect between manufacturing and non-manufacturing industries or between large firms and small and medium-sized firms. In short, there is a serious manpower shortage across all industries regardless of firm size. In particular, promoting reskilling to expand the pool of workers with digital skills is an urgent task.

The third challenge is the risk that reskilling efforts may slow down as a result of moves to bring business operations back to Japan for economic security reasons. Benefits gained from overseas production activity include not only a cost reduction effect but also a rise in productivity due to the intensive allocation of freed-up domestic business resources into research and development and other business processes that create higher added value. According to the results of an analysis of 5,550 Japanese manufacturing firms that I conducted with Ryuhei Wakasugi, President of the University of Niigata Prefecture, and Professor Tomiura who was mentioned earlier, indeed, outsourcing business processes to foreign countries raises the productivity of firms on average.

If manufacturing industries bring more business operations back to Japan from the rest of Asia amid labor shortages, it is possible that any increase in productivity may be sacrificed as a result of the intensive allocation of domestic manpower to the returned operations, or that reskilling efforts aiming for DX may be constrained. When firms shift products that depend heavily on foreign supply chains to domestic production for economic security reasons, it is necessary to pay attention to the impact on domestic labor distribution.

The reallocation effect may arise at the level of individual business establishments (business divisions) within firms, especially for multi-product firms. As the shift to data-driven businesses grows around the world, it is an urgent task for firms to reallocate their internal resources through reskilling. Increased human capital investment will raise the productivity of firms, making it possible to capture market shares globally as well as in the domestic market. The benefits thus obtained are expected to be returned to workers in the form of wage increases.

* Translated by RIETI.

November 29, 2022 Nihon Keizai Shimbun