Following the three-year administration of Prime Minister Kishida Fumio, Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru has been inaugurated, and the election of the House of Representatives is approaching.

Looking back on the Japanese economy for the last three years, the moderate deflation has ended, and the consumer price index (excluding fresh food) has been showing annual increases above 2% since April 2022. The quantitative and qualitative monetary easing was also terminated and an economy with positive interest rates has returned. In terms of nominal values, the Japanese economy has thus changed significantly since before the COVID-19 pandemic.

On the other hand, the growth rate of Japan's real gross domestic product (GDP) has long been on a declining trend, and real interest rates still remain negative. On the fiscal front as well, the general government primary balance including social security funds (against GDP) has yet to recover to pre-pandemic levels. This suggests that many structural reforms that were left unaddressed since Abenomics have not progressed. I will discuss the economic and fiscal policies that the new administration should prioritize.

◆◆◆

Regarding economic policy, the government should aim to achieve sustainable real wage increases that exclude the impact of price fluctuations. In June 2024 real wages turned positive year-on-year for the first time in 27 months, but have since been fluctuating. Without an increase in labor supply, upward pressure will be felt in real wages, but maintaining and even accelerating wage increases is essential. To achieve this, one or more of the following measures can be implemented: (1) Increase the labor share of income; (2) Enhance the purchasing power of wages (currency); and (3) Increase the total income of the economy (GDP).

The labor share of income is determined in the long run by factors including production technology and the level of competition in the goods and labor markets. From around 1980 to 2000 in Japan and in the United States, the labor share of income decreased due to the advancement of information technologies. In the United States, the labor share of income has continued on a declining trend since then due to increased investments in intangible assets (such as customer data, brands, software, innovative technology, etc.) and accompanying increased concentration in the goods market.

In contrast, in Japan, investment in intangible assets has slowed, while the goods market has become more competitive, and the labor share of income has not been declining in recent years. Accordingly, there is little room for policy interventions to increase the labor share of income. A large increase in the minimum wage could possibly raise the labor share of income, but there is concern over adverse effects such as companies tightening hiring standards. There is no evidence that tax measures to promote wage increases actually promoted wage growth.

How have the government's price control measures against rising prices worked to enhance purchasing power of wages? The fixed tax reduction and subsidies for gasoline under the Kishida administration had temporary effects; however, if these measures are not narrowly targeted, they incur significant costs and are not sustainable policy measures in the long term. If the yen becomes stronger, it will stabilize prices and will contribute to enhancing purchasing power, but exchange rates fluctuate based on domestic and foreign monetary policies and are unpredictable.

Ultimately increasing GDP in the long term and enhancing the productivity of the economy as a whole is the most important factor. In addition to steadily implementing such measures as promoting technical innovation and advancing digitalization and greening, policy measures that leverage market mechanisms are important in making maximum use of existing resources, such as human resources, goods and services, and capital.

Regarding human resources, the key is how smoothly labor force mobility can be increased. It is also necessary to design systems that allow for appropriate compensation during unemployment and effective reskilling so that reemployment can occur rapidly and effectively. An urgent discussion is necessary regarding how expenses for such programs should be shared between the public and private sectors.

If labor force mobility is increased smoothly, the gap in wages between regular workers and non-regular workers will narrow. Also, if career advancement opportunities increase with higher labor mobility, more workers will be motivated to acquire new skills, and companies will be required to respond to this demand. This could lead to increased investment in human capital in Japan, where such investment has been less active compared with the United States or other countries. With more efficient allocation of resources and the accumulation of human capital, real wages will increase sustainably.

Regarding capital, the launch of the new NISA program and other measures under the Kishida administration led to a shift in household assets from savings to investment in shares and investment trusts.

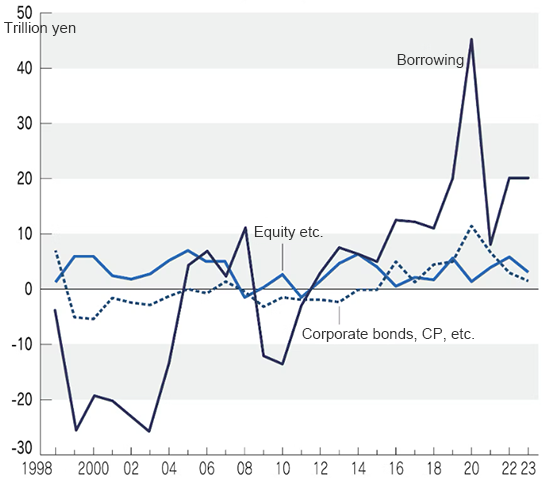

It is also important to promote the expansion of corporate fundraising through capital markets. Since the implementation of Abenomics, companies have increased funding through debt financing, including low interest borrowing from banks and corporate bonds, but fundraising through issuance of shares has seen little growth (see the figure below). Equity financing is particularly suitable for the growth of startups, providing capital for intangible assets as they typically lack collateral for other sources of financing. It is necessary to further expand equity financing and financial market participation through improvement of startup governance and human resource development in venture capital firms.

Regarding goods and services, policy measures for SMEs, which are major players in these markets, should be reviewed. SMEs face various problems, such as the aging of business owners, lack of successors, and labor shortages. There are limitations in solving these problems only through conventional uniform tax incentives or broad subsidies. Support that leverages market mechanisms would be most effective.

For example, promoting the reliable disclosure of financial conditions and human capital for SMEs and utilizing subsidies for that purpose will produce results in their funding, business succession, M&A, and human resource acquisition. If allocation of resources in SMEs is optimized, it could lead to broad-based and sustainable real wage increases.

◆◆◆

What fiscal policy should the new administration adopt? First of all, they need to understand that as monetary policy is normalized from the era of unprecedented quantitative easing, fiscal space is constrained. The Kishida administration adopted an extravagant fiscal policy, such as fixed amount tax reduction, and while tax revenues increased with economic expansion, rapid inflation or the depreciation of the yen did not occur as a result of government spending. This “successful” experience could provide incentive for the new administration to increase expenditures.

However, this experience was supported by ultra-loose monetary policy, and if interest rates eventually exceed nominal growth rates, increasing budget deficits represents a dangerous gamble. The government should focus on achieving its goal of a primary balance surplus for national and local government finances in FY2025. There is also an urgent need to secure funding sources for national defense and measures to address the declining birthrate.

The government should focus on providing solutions where markets cannot. A large-scale negative shock, such as a pandemic, a large earthquake, flood or other natural disaster cannot be covered only by private insurance, and national fiscal policy is expected to fulfil an insurance function. As disaster-stricken households and companies spend much of their income on restoration, targeted measures will produce large economic effects. The government should secure fiscal space during normal times in order to prepare for possible crises and should stop subsidies promptly when recovery from a crisis is achieved.

As is evident from my evaluation of effects of the support measures for SMEs amid the COVID-19 pandemic, undertaken with Project Associate Professor Tomohiko Honda of Kobe University and others, long-term continuation of broad coverage measures can lead to the preservation of inefficient companies. This can eventually lead to the stagnation of real wages. Regarding natural disasters, one option is to predict and disclose potential fiscal expenditures based on damage estimates. Government policies should be determined based on evidence and terminated in a timely manner once achieved.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

October 11, 2024 Nihon Keizai Shimbun