As many central banks other than the Bank of Japan (BOJ) are moving toward monetary tightening in order to curb inflation, financial and exchange markets have become unstable. This article considers how monetary policy should be conducted from a relatively long-term perspective.

The BOJ for the first time introduced a target for growth in the consumer price index (CPI) in March 2001, when it adopted the quantitative easing policy. At first, the BOJ planned to maintain that policy until the CPI growth rate rose to at least zero percent, but later, it made a policy change and raised the target rate to around 1%. In January 2013, immediately before adopting the qualitative and quantitative easing policy, the BOJ set a 2% target.

One of the objectives in conducting monetary policy based on an inflation target is to influence the people’s expectations of future monetary policy and prices by making a commitment to maintaining the current policy until the target is achieved. If the people believe in the commitment to monetary easing, long-term interest rates are expected to decline, leading to an earlier economic recovery. Setting an inflation target has been regarded as an effective measure particularly at a time when the economy has fallen into a liquidity trap with short-term interest rates stuck around zero under deflation.

The inflation target has been raised to 2% mainly for two reasons. First, if the inflation target had been kept at zero, short-term interest rates, too, would have remained stable at around zero, leaving no room for future interest rate cuts. A 2% target was better suited to creating room for future interest rate cuts. Moreover, if the BOJ had gone it alone in setting a lower target when other major central banks were adopting a 2% target, it would have faced the risk of being considered reluctant towards monetary easing, a perception that could have caused the yen to appreciate against other currencies.

The qualitative and quantitative easing policy under the 2% inflation target rectified the strong yen and underpinned overall demand, including capital investment and exports. In 2018, the CPI growth rate rose to around 1%, marking Japan’s exit from deflation, but the 2% target was reached only recently. As the people’s inflation expectations turned out to be more rigid than assumed, the inflation target failed to fully exercise the effect of boosting the real economy by influencing inflation expectations.

The funding situation also affects companies’ price-setting behavior. Companies in a difficult funding situation are more likely than their peers in an easy funding situation to set lower prices in order to secure cash and deposits by drawing down inventories. Indeed, as a result of a study that the author conducted together with Professor Miho Takizawa of Gakushuin University and Associate Professor Kenta Yamanouchi of Kagawa University under the auspices of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry, it was confirmed that companies with a smaller amount of liquid assets, including cash and deposits, tend to set lower prices. However, monetary easing did not have an impact on differences in price-setting behavior.

◆◆◆

Recently, due to steep rises in resource prices around the world and the sharp depreciation of the yen, the CPI growth rate (year-on-year), excluding fresh food prices, has risen above 2%. As the BOJ’s stance of maintaining monetary easing has pushed down the yen’s value, the yen’s real effective exchange rate, which is adjusted for differences between the prices levels in Japan and in other countries, is at the lowest level in the past 50 years.

While the yen’s sharp depreciation brings benefits to export-oriented companies and inbound tourism (foreign tourists’ visits to Japan)-related companies, it reduces real income through inflation. Inflation has a particularly large impact on low-income families.

Over a long term of several to 10 years or so, the yen’s exchange rate is presumed to be corrected to a level commensurate with the purchasing power parity in Japan. However, the correction process may not necessarily proceed at a moderate pace. There is the risk that the correction process could become rapid and excessive (overshooting) due to factors such as the unwinding of yen-carry trade.

Another risk from the BOJ maintaining monetary easing is a ballooning of the fiscal deficit. The author, together with Associate Professor Daisuke Miyakawa of Hitotsubashi University and Shuji Watanabe of Nihon University, estimated the private-sector demand function and the governmental supply function in the primary market for government bonds by maturity of government bonds and analyzed the effects of the BOJ’s government bond purchases.

It was found that in Japan, the BOJ’s government bond purchases’ effect of lowering yields is relatively strong due to institutional investors’ preference for specific maturities. However, it was found that this effect has been partially offset by the government’s strategy of flexibly increasing the issuance of government bonds in maturity zones with reduced yields while lengthening the average maturity at issue for overall government bonds. In terms of government debt management, the government enjoys benefits in the form of reduction of interest payment cost, and the incentive for cutting back on the fiscal deficit is weakening.

Moreover, we cannot ignore the risk that the prolonging of low interest rates could allow inefficient companies to remain in business. Low interest rates make it easier for companies to enter new business areas, but if the abovementioned negative effect becomes sufficiently strong, resource allocation will become inefficient and keep productivity growth stagnant and hold down real wages.

Furthermore, the yield curve control operations, particularly unrestricted government bond purchases at the BOJ’s bid prices, have made the market dysfunctional. For example, although we would usually be able to determine whether the ongoing inflation is transitory, as the BOJ has insisted, based on information available from the bond market, it has become difficult to make the determination.

If government bond prices (yields) remain fixed at a certain level for an extended period of time, that raises the risk that speculative trading may arise, making it necessary to expand the scale of government bond purchases as a countermeasure. Even though speculative trading may be countered in this way, a decline in the volatility of government bond prices could reduce opportunities for arbitrage trading, eroding the depth of the market. The market dysfunction could deteriorate further, causing government bond issuance to continue increasing without any warning from the market.

◆◆◆

As a result of the pursuit of the 2% inflation target as the basis for maintaining the current policy, long-term risks have accumulated. However, the inflation target in itself has the effect of stabilizing the people’s inflation expectations and reducing uncertainty. Maintaining a certain level of inflation rate in the long term may also lead to increases in the nominal economic growth rate and productivity.

A joint study by Miyakawa, my partner in the aforementioned study, and Professors Koki Oikawa and Kozo Ueda of Waseda University showed that a high nominal growth rate leads to an increase in the market shares of companies that actively promote innovation. However, the benefits of high nominal growth like this take time to be realized, as flexible labor mobility between companies is a precondition.

Therefore, rather than abandoning the 2% target, which now serves as the basis for maintaining the current policy, the author would like to propose repurposing it as a long-term goal and tolerating short-term deviations from the target rate. With that as a premise, the author’s proposal also calls for switching back, for the moment, from the yield curve control to a quantitative easing operation using the amount of government bond purchases as an operation target. Leaving it to the market to determine the price level (yield level) will enable the market to function more effectively and help to better exercise fiscal discipline.

When controlling short-term interest rates, setting a target inflation rate that is desirable from a long-term perspective and adjusting short-term interest rates in accordance with the actual inflation rate and supply-demand gap (Taylor rule) is considered to be an ideal form of policy management, and the same principle should be applied to quantitative monetary easing as well. Currently there are significant inflationary pressures, such as the resource price rises, while the supply-demand gap that followed the onset of the COVID-19 crisis is shrinking. Although there are uncertainties, including the effects of monetary easing overseas and the situation of COVID-19 infections in Japan, it is appropriate to aim to roll back the quantitative easing as the first step.

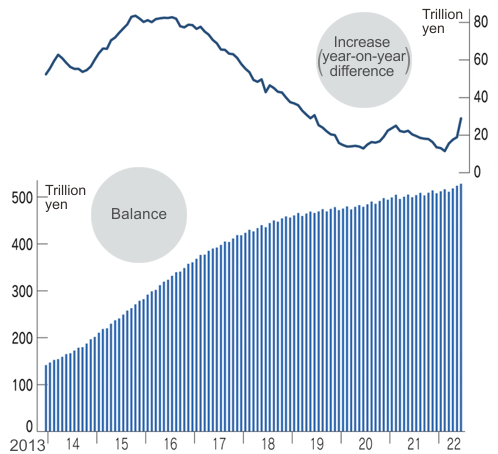

Since September 2016, when the yield curve control was introduced, the growth in the balance of long-term government bonds held by the BOJ has continued to slow, except for the recent period in which purchases have been increased in order to deal with the impact of COVID-19 (see the figure above). One possible option is to gradually reduce the degree of quantitative easing, as the BOJ was doing before the COVID-19 crisis. It goes without saying that making such a policy change has the risk of triggering a steep appreciation of the yen or a rapid rise in long-term interest rates. Nothing could be gained if the policy change poured cold water on the real economy. Making a policy change requires careful explanations to stakeholders. However, the risks associated with the continuation of the current policy outweigh any risks associated with a policy change.

* Translated by RIETI.

July 7, 2022 Nihon Keizai Shimbun