PDF version [PDF:276KB]

Introduction

This article is intended to consider the possibilities of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum as a venue for soft law. Since its establishment in 1989, APEC has continued to be an important regional framework in the field of economic cooperation in the Asia-Pacific region. I will focus on APEC’s unique position as a venue for the use of soft law, and also look at climate change as a case study for considering the implications of being a venue for soft law. First, I will review the history and results of APEC’s use of soft law. Then, in the context of climate change, I will examine aspects including whether the Paris Agreement uses the APEC Way. Finally, I will consider APEC’s future potential in terms of its ability to create soft law.

Relationship Between Soft Law & Hard Law

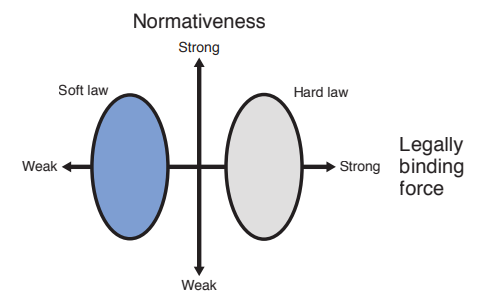

In general, the existence or absence of legally binding force is frequently mentioned when discussing the relationship between soft law and hard law. In addition to the strength or weakness of legally binding force, it is easy to understand the relationship between the two by considering the strength or weakness of normativeness. We can think of legally binding force and normativeness as two axes (Chart).

If there is legally binding force, we can imagine that penalties are designated, and a party that violates a rule meant to be observed is penalized in a way that puts them at a disadvantage. At the same time, this raises the point of whether participants should remain in arrangements where legally binding force exists, or whether they should remove themselves from them. This means that hard law has strong legally binding force, whereas legally binding force is weak for soft law.

On the other hand, if we add the perspective of normativeness, a view emerges that does not depend on the strength or weakness of legally binding force. International norms set objectives for participants and stipulate participants’ standards of conduct. If normativeness is strong, participants will be more compelled to act according to the indicated purpose, and will act according to the standards of conduct.

This, however, raises the major issue of deviations from the standards. If it is obvious that the standards do not have legally binding force, what kinds of restrictions are placed on participants, and should they observe those standards or not? In addition, how should violators be dealt with? These are the issues we could face.

History & Results of Soft Law Within APEC

APEC was launched in 1989 with 12 economies in the region, with China, Hong Kong (now Hong Kong, China), and Chinese Taipei added in 1991, Mexico and Papua New Guinea added in 1993, Chile added in 1994, and Russia, Peru, and Vietnam added in 1998. Further expansion with additional economies was frozen at this point. During this time and continuing to the present, APEC has not been a legal entity, but rather an organization for deliberation related to economic cooperation among members. APEC’s activities have developed in a way that relies on a form of normativeness.

From its outset, APEC operated in a manner called the “APEC Way”. This meant that participating members first reached a consensus, and that those economies that were able to implement the decision first did what they could. This method assumed that the delayed economies would implement the decision in due course. From the second half of the 1990s, a proposal was made at APEC for Early Voluntary Sectoral Liberalization (EVSL), and an attempt was made to implement it. At that time, however, there was strong pressure to eliminate tariffs by sector, and APEC was not successful in implementing this kind of hard-law approach.

Against this backdrop, there came to be a rather strong focus on APEC’s role as an “incubator of ideas” where various ideas were put forth, and programs that could be implemented grew out of those ideas.

Examples of APEC as an Incubator of Ideas

We can see several examples of APEC functioning as an incubator of ideas. The first is with regard to trade liberalization for environmental goods, where APEC drew up a list that it took to the World Trade Organization (WTO), and negotiated an agreement with the WTO on goods subject to tariffs. In 2012, agreement was reached within APEC on the list of environmental goods for which tariffs would be lowered or eliminated, after which negotiations took place with the WTO on an agreement for environmental goods.

The second example is in the area of regional economic integration, which was not carried out by APEC itself, but APEC played a supporting role for efforts taking place within the region. The Yokohama Vision of 2010 laid the path for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) to become a Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP) in the future. In this way, APEC gave a boost to regional economic integration.

The third example is in the area of economic and technological cooperation, a major core area within APEC. A rough agreement was reached in 2014 in the form of a guidebook for quality infrastructure, and this was incorporated as a G20 principle at the G20’s meeting in Osaka in 2019 as the “G20 Principles for Quality Infrastructure Investment”.

In addition, as countries began to address digital economies, when APEC was unable to take a unified approach, it identified the things it was able to do within the organization and acted as a pathfinder toward the compilation of what in 2011 became the APEC Cross-Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) System, which was closer to a set of rules. Instead of being a set of rules for all APEC economies, these were intended to promote sharing among certain economies.

Normativeness of the APEC Vision

In talking about the APEC vision, I would like to consider the normativeness it holds. An economic vision was put forth at the first summit meeting in 1993. The next year, in 1994, the Bogor Goals were set in Bogor, Indonesia. The Bogor Goals established the objective of liberalization by 2010 for developed economies, and by 2020 for developing economies. And after that, various types of normative directions and standards of conduct for the long term were set based on the Bogor Goals. In 2020, the APEC Putrajaya Vision 2040 was formulated as a set of post-Bogor objectives.

The aim in 1993 was to create an Asia-Pacific economic community, and an “economic vision” was put forth. This included elements such as a spirit of openness and partnership, supporting an open international trading system, reducing trade and investment barriers, and sharing the benefits of economic growth. This vision was formulated by an Eminent Persons Group chaired by C. Fred Bergsten.

At the 1994 summit meeting, a target of liberalizing trade and investment was set for 2010 for industrialized economies, and by 2020 for developing economies. This was expressed in the statement as “Our goal of free and open trade and investment in the Asia-Pacific no later than the year 2020”.

In 2020, in contrast, the APEC Putrajaya Vision 2040 set out to build “an open, dynamic, resilient and peaceful Asia-Pacific community” by 2040. This vision expanded the scope of the Bogor Goals, designating three economic drivers: (1) Trade and Investment; (2) Innovation and Digitalization; and (3) Strong, Balanced, Secure, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth. Things like the inclusion of sustainable and inclusive growth, and addressing digitalization, were major steps.

Before formulating the APEC Putrajaya Vision 2040, the APEC Vision Group discussed what kind of visions should be put forth, and its report was released in 2019. That report stated that the governments’ vision should include a “peaceful and interconnected Asia-Pacific community”. The APEC Putrajaya Vision 2040 took these discussions into account.

Trade & Liberalization Norms

In thinking about trade and investment liberalization as a set of norms, there has been much support for an open trading system, and APEC has been involved in the progress taking place toward liberalization within the region. In legal terms, progress has been made with free trade agreements (FTAs) and regional trade agreements (RTAs) since the 2000s, and APEC can be said to have been functioning as a place from which to support these from behind the scenes.

Since 2020, APEC has directly faced the issue of how to promote discussions on how to build on these FTAs and RTAs further. The two major issues are to support a free and open multilateral trade system, and to progress regional economic integration with the Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP) in mind.

The APEC Putrajaya Vision 2040 positioned trade and investment as the No. 1 economic driver, stating that APEC would work to deliver “a free, open, fair, non-discriminatory, transparent and predictable trade and investment environment”. The vision stated that to deliver a multifaceted trade system, it would first support the WTO, and second, it would promote the FTAAP agenda.

Input and support from the private-sector APEC Business Advisory Council (ABAC) can be seen as important to APEC governments’ discussions of these issues. FTAAP discussions in 2021 said that attention should be paid to ABAC’s priorities, and the 2020 Leaders’ Declaration indicated that the ABAC side had emphasized the importance of the WTO.

Climate Change: Is the Paris Agreement the APEC Way?

Next, I would like to discuss climate change. When the Kyoto Protocol was signed, industrialized countries were legally bound to greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets, and were subject to penalties if those targets were not met. This was a very lenient structure, but a country faced these penalties if it was not able to meet this target. As a country that could not meet its target, Canada withdrew from the Kyoto Protocol, but there were various possible ways to respond.

The Paris Agreement, in contrast, took more of a soft law approach, with less severe penalties and the countries’ various commitments themselves less stringent, giving a strong sense of being voluntary. We can argue that the United States’ temporary withdrawal was about deviation from the normative aspects of climate change rather than about various legal points.

Looking at APEC’s perspective on creating norms with regard to climate change, the impression is that the biggest push came in 2007. That was the year it issued the Sydney APEC Leaders’ Declaration on Climate Change, Energy Security and Clean Development. Later that year, discussions under the Bali Plan of Action took place in the course of United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) negotiations, which led to the formulation of the Copenhagen Accord at COP13 in 2009.

On the other hand, because climate change still had a marginal presence within APEC in 2020, the APEC Putrajaya Vision 2040, where climate change is included as one of the items in “all environmental challenges” under the third economic driver of Strong, Balanced, Secure, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth, will be important in determining the extent to which it will become mainstream going forward.

Considering the relationship between climate change and energy, however, the connection with energy transition and energy resilience emerges. This trend has gradually been emerging since 2020. Although the 2021 APEC Leaders’ Declaration did not refer specifically to the Paris Agreement or COP26, it did acknowledge that urgent, specific action to address climate change was necessary. It also recognized commitments to net zero emissions and carbon neutrality. Action related to climate change has also been further integrated into appropriate work streams at APEC.

In 2021, ABAC presented a set of Climate Leadership Principles, as a private-sector response that outlined how businesses should respond to climate change. With regard to how the government APEC side should respond to the climate side, ABAC called for a discussion of how to develop sound, mutually-reinforcing, WTO-consistent and coordinated trade and other policy responses to climate change.

Possibilities for APEC: Will New Soft Law Emerge?

Finally, I would like to consider the possibilities for APEC going forward. Could one breakthrough for APEC be creating norms as an incubator of ideas? A second point is that given APEC’s membership, with the US, Asian countries, China, and Russia, there are major questions as to what it can do at this time. The third point I would like to consider is how to view its relationships with non-governmental stakeholders. And fourth, given that above all, one of APEC’s strengths is its ability to carry out specific projects, how can this strength be used?

In terms of areas in which APEC should work to create new soft law, the first could be the promotion of a trade and investment agenda that includes the pursuit of a free and fair economic order, rectification of measures that distort markets, and the promotion and strengthening of high-level, comprehensive economic cooperation. The second could be the promotion of a digital agenda. This could be through the creation of rules and cooperation toward the realization of Data Free Flow with Trust (DFFT). The third could be the promotion of an agenda for climate change and energy. The achievement of carbon neutrality and stable and inexpensive energy supplies could be important themes.

Thailand, the host economy for APEC in 2022, has designated its priorities as Open, Connect, Balance. It is also pursuing a Bio-Circular-Green economic model. These Thai-led efforts are expected to be a specific step toward measures in the broad range of areas covered by the APEC Putrajaya Vision 2040. Preparations for APEC from 2023 will also be important. The US has been chosen as APEC’s host for 2023. The G7 meeting that year will be held in Japan.

One last thing I would like to point out is the importance of cooperation with academia. The revitalization of the APEC Study Centers in each member economy and the overall APEC Study Center Consortium would help to invigorate APEC’s activities going forward.

This article first appeared on the July/August 2022 issue of Japan SPOTLIGHT![]() published by Japan Economic Foundation. Reproduced with permission.

published by Japan Economic Foundation. Reproduced with permission.

July/August 2022 Japan SPOTLIGHT