Over the past 20 years or so, Latin American economies have pursued the path of globalization. The globalization in Latin America is divided into the South American type, which is characterized by the growth of the resources sector, and the Mexican-Central American type, which is notable for the development of global value chains (GVCs) integrated into North America.

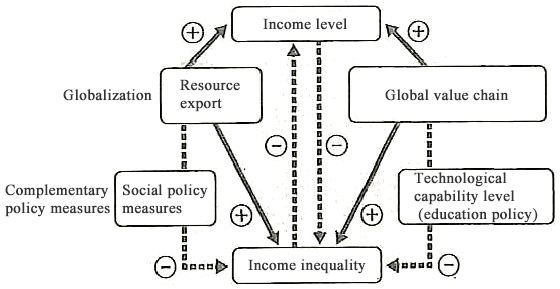

The figure below shows the results of a study conducted jointly by this author and Assistant Professor Yoshimichi Murakami of Kobe University with regard to Latin American economies.

Although both types of globalization directly have a positive impact on income (increase the income level), they also work to expand income inequality. As a result, the net effect may be a reduction in income level. However, the expansion of income inequality due to resource exports may be partially offset by the enhancement of social policies, while the expansion of income inequality due to GVC integration may be partially offset by an education policy that promotes improvement of the technological capability level. Therefore, implementing appropriate policies to complement globalization can be expected to lead to economic growth accompanied by the shrinkage of inequality.

Brazil achieved poverty reduction and economic growth under the Workers' Party (PT) governments (2003 to 2016) thanks to the resource boom and social policies financed by resource-related revenues. However, with the end of the resource boom, the economy slowed down and the unemployment rate rose. Amid the deterioration of the fiscal situation, the government was unable to implement additional social policies and was forced to raise utilities fees, straining the lives of families in the middle class and lower income brackets.

Brazil failed to extract the expected economic boost from the two recent international events that it hosted, the 2014 Soccer World Cup and the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympics. Some of the legacy facilities of those events have been left in a state of neglect due to a funding shortages, becoming symbols of frustrated hopes. This situation coincided with the revelation of the massive corruption scheme that led to the guilty verdicts and imprisonment of former President Lula and other senior members of the Workers' Party, fueling public outrage.

Under those circumstances, the presidential election runoff was held on October 28, 2018. Jair Bolsonaro of the Social Liberal Party (PSL) defeated Fernando Haddad of the Workers' Party. Mr. Bolsonaro will take office in January 2019.

Mr. Bolsonaro is a veteran politician who has served as a member of the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of the National Congress of Brazil. He was educated at a military academy and is still registered with the military as a reserve serviceman. As for his political-ideological position, glimpses have been provided by his show of strong disgust at what he described as the authoritarian, corrupt parliamentary politics of the recent government and sympathy with the repressive government during the period of military rule (1964 to 1985), along with his comments suggesting tolerance for the use of torture and the death penalty to eradicate corruption and restore public order. That he is a politician of an anti-liberal, conservative bent is also indicated by his opposition to abortion and same-sex marriage, and his comments showing disregard for women and the poor, while simultaneously emphasizing respect for individuals' rights and choices, including his pledge to loosen gun ownership restrictions.

What the Brazilian people expect most from Mr. Bolsonaro is eradication of corruption and restoration of public order. They supported Mr. Bolsonaro as he criticized the law enforcement conducted within the existing legal framework as insufficient, suggesting the possibility of radically changing the status quo through authoritarian rule. His support base is probably comprised mainly of people matching the following profiles: people in the middle class and higher income brackets, men, people in southern and central western Brazil, a region which has achieved remarkable economic growth due to exports of agricultural products in recent years, and younger generations of people who are not aware of the repression under the military rule.

It would not have been surprising if the Workers' Party had lost the presidential election by a huge margin given that its economic policies based on resource exports and social policies were no longer popular and the party was under criticism due to the corruption scandal. However, in northeastern Brazil, mainly populated by low-income people, a majority of voters voted for Mr. Haddad, the Workers' Party's candidate, as they were worried about Mr. Bolsonaro's comments that smacked of authoritarianism and wished to continue enjoying the economic benefits of the Workers' Party's initiatives to create jobs and provide public assistance to the poor.

A center-right party that would normally have attracted votes from people opposed to the Workers' Party also fell victim to the loss of public trust in existing political forces due to the wave of media stories about corruption and abuse of political power that were reported daily. The fact that Mr. Bolsonaro was affiliated with a small party and was keeping away from the government and establishment parties worked to his advantage in the presidential election. His stance of thoroughly pursuing the path of an outsider, rather than seeking to form a coalition with other parties, was welcomed by the Brazilian people, who desired strong leadership that would be likely to change the status quo without constraint.

As a campaign pledge concerning economic policy, Mr. Bolsonaro vowed to place emphasis on liberalization and privatization and avoid economic intervention, thereby realizing a small government with a limited budget.

In the past, Mr. Bolsonaro accused the Cardoso government, which privatized Vale do Rio Doce, of selling the state-run mining company cheaply at the expense of Brazil's national interests. He also emphasized the need for a managed exchange rate system. However, as an election campaign pledge, he vowed to entrust economic policy management to Mr. Paulo Guedes, an economist with a doctorate from the University of Chicago who is known for his expertise in the fields of securities and investment finance, and expressed support for liberalization and small government policies being advocated by Mr. Guedes.

Among the specific policy measures under consideration are: promoting a thorough privatization without sparing the oil sector as a sacred cow; reducing tariffs and shifting emphasis in trade policy from regional integration to bilateral agreements; abolishing corporate subsidies; unifying the income tax rate and imposing tax on financial transactions and on investment and dividend income as a measure targeted at the wealthy class. As for macroeconomic policy, the new government will strengthen the independence of the central bank while maintaining the following three pillars of economic management: the current inflation target, the primary balance surplus target, and the floating exchange rate system. In the financial market, both stock prices and the Brazilian currency, the real, are rising amid high expectations for the arrival of the new government.

However, the reforms advocated by Mr. Guedes need parliamentary approval for many institutional changes, including with respect to public finance, the public sector and labor contracts. When a constitutional amended is required, it is necessary to obtain a three-fifth support in each of the lower and upper chambers of the Congress. The pension reform promoted by the outgoing government, which is essential for fiscal consolidation, is likely to be carried over to the new government.

Therefore, the new government's relationship with the Congress is important. The situation of the Congress of Brazil, characterized by the presence of many small parties, has not changed after the presidential election. Previously, the governing parties formed a coalition with many other parties in order to secure support in the Congress and allocated administrative posts and budgets in consideration of the coalition partners' interests. This arrangement was a contributing factor to the corruption and the bloated size of government institutions.

If the Bolsonaro government, which rejects this arrangement, is to carry out various reforms, it is essential to obtain the people's support, which can be used as political justification to bring the Congress around and move toward reform. Since the 1990s, two governments—the Collor government and the Rousseff government in its second term—experienced the impeachment and removal from office of the incumbent presidents after clashing with the Congress. The possibility cannot be ruled out that the Bolsonaro government will follow the same fate.

A change is also expected in Brazil's relationships with other countries. The Workers' Party governments cooperated with anti-American leftist governments in countries such as Venezuela and Bolivia in order to achieve a regional integration of liberal forces. In contrast, the new government plans to discard this approach, cooperate with new conservative governments that have been inaugurated one after another in Argentina, Chile and Paraguay, and place emphasis on bilateral negotiations, including with developed countries.

Brazil's relationship with China rapidly grew in terms of trade, investment, and finance amid the natural resources boom. However, Mr. Bolsonaro has expressed wariness, saying: "China isn't buying in Brazil, China is buying Brazil."

However, Brazil's relationship with China is unlikely to turn confrontational overnight. China will continue to be the most important natural resource market for Brazil, and investment from China is essential for promoting privatization. All the same, the new government is expected to change their relationship with China into one that is more favorable to Brazil's national interests.

On the other hand, Mr. Bolsonaro is praising Japan and South Korea for achieving national development through education and the promotion of science and technology. If the Japanese government is sensitive in recognizing and reacting to friendly signals from the new Brazilian government, it may be able to restore its presence in Latin America, which has faded in recent years because of China's active efforts to strengthen its relationship with the region.

Even so, there is no doubt that Brazil will make overt efforts to promote its national interests in its relationship with Japan, as in the case of its relationship with China. If those efforts show signs of protectionism, Japan will need to pursue political dialogue in order to call on Brazil to redress its stance.

* Translated by RIETI.

November 6, 2018 Nihon Keizai Shimbun