One of the sectors that is most vulnerable to damage from the COVID-19 crisis is the small and medium-size enterprise (SME) sector. The future course of the Japanese economy depends on how the COVID-19 crisis affects SMEs, which account for around 70% of the overall workforce and more than 50% of the total added value created in Japan. Since before the crisis, the growth of SMEs was slow compared with that of large companies in Japan, and this trend could become more pronounced.

This article considers how to promote the growth of SMEs, a rather complicated issue, from the viewpoints of corporate dynamism and the government's SME policy.

♦ ♦ ♦

There is a consensus that SMEs are in a weak position compared to larger enterprises. As a result, support for SMEs can be easily accepted by society, so generous protective measures have been provided over a long period. For example, SMEs are subject to lower tax rates than those applied to large companies. Regarding tax enforcement as well, it is quite commonplace that SMEs which chronically report losses are exempted from tax payment responsibilities. There are several government-affiliated financial institutions specialized in lending to SMEs. These generous support measures certainly affect borrowers' behavior.

Companies whose workforce size or capital amount is below a certain threshold are universally regarded as SMEs under Japan's legal framework. Therefore, some large companies that may effectively be categorized as large companies opt to reduce their capital amount in the hope of becoming eligible for a lower tax rate when they are financially struggling.

Such decision-making means that companies with growth potential deliberately remain among the ranks of SMEs. Granting preferential treatment to SMEs on a permanent basis dampens their appetite for growth and provides an incentive to retain the SME designation. By international standards, SMEs have a large share of Japan's workforce and output, and this probably has something to do with the preferential treatment that they have long enjoyed.

Moreover, every time the Japanese economy enters a severe recession, support is provided to SMEs on a large scale. That is understandable as an immediate reaction given that SMEs lack some of the capacity to withstand macro shocks. However, support measures intended for the purpose of emergency relief are maintained for a long time and similar measures were implemented repeatedly. Particularly, since the late 1990s, "emergency" relief measures have continued to be implemented.

Those "emergency" measures are starting to have an impact that is slightly different in nature from the expansion of SMEs' share in corporate sector economy caused by the distortive effect of preferential measures provided in normal times. The "emergency" measures are creating "zombie" companies, which should have been expelled from the market due to going out of business in times of recession, but which have been kept alive through financial aid and other support. A similar phenomenon came to light during the Japanese financial crisis in the latter half of the 1990s and later, mainly with regard to large companies in ailing industries. However, in recent years, the presence of "zombies" among SMEs has become a cause for concern. Those companies, which could go out of business any time, tend to be inferior in business performance and growth potential.

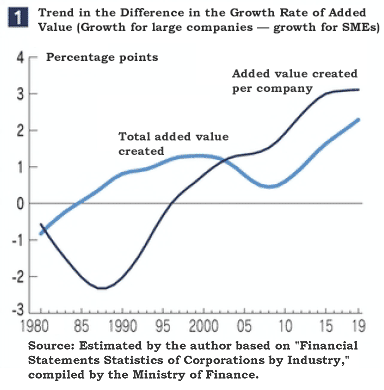

Broadly speaking, the general principle that protective policy weakens industrial competitiveness in the long term applies to the SME sector as well. The difference between the growth rates of added value created by large companies and SMEs continues to widen as a trend (see Figure 1).

How can the growth potential of the SME sector be increased? In this respect, the viewpoint of economic dynamism is important.

Vigorous shakeouts sweep through SME sectors, expel existing companies and bring in new entrants. Inefficient companies go out of business while growing SMEs are transformed into large companies. Aspiring companies wishing to grow advance into the market. A dynamic mechanism like this invigorates entire industries. However, generous support works to curb this mechanism. Inefficient companies remain in the market, while companies with growth potential refrain from venturing out of the SME sector. The window of business opportunities becomes narrower for new market entrants, dampening the appetite for entry.

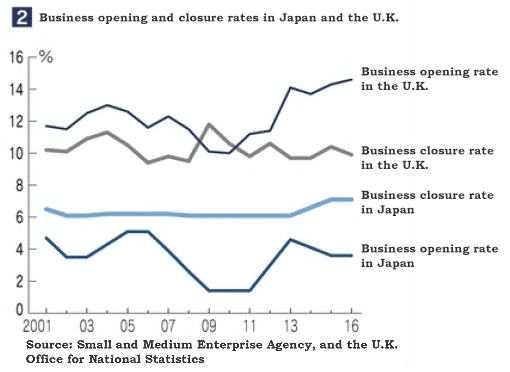

The stagnant dynamism of the Japanese economy has long been under discussion. The business opening and closure rates in Japan are around half of the levels in the United States and Europe (around 10%) (see Figure 2).

To realize sustainable development of the SME sector, it is essential to promote growth accompanied by economic dynamism. The awareness of the need to do so has taken hold, as exemplified by the amendment of the Small and Medium-sized Enterprise Basic Act of 1999. However, in reality, the road ahead is rough. One background factor is that the Japanese economy has experienced a succession of large-scale economic shocks, including the domestic financial crisis that started in 1997 and the Lehman Shock in 2008. In emergencies, priority inevitably tends to be placed on support measures intended to maintain the status quo by keeping existing companies afloat.

Moreover, there is a complicated web of deep-seated factors. Let me cite three major factors. The first factor is the historical background of institutional systems. During the process of the formulation of the government's SME policy in the postwar period, SMEs were regarded as forming a weak sector which was set apart from large companies achieving rapid growth with the support of industrial policies, and which was unable to ride on the wave of reconstruction and high growth. Under this perception, the SME policy was characterized as part of an industrial policy that emphasized the viewpoints of promoting growth under protective care. This starting point has strongly influenced the nature of Japan's SME policy until now.

Second, it is difficult to make a policy change because of the social policy element of the government's support for SMEs. The smaller a company is, the more blurred the boundary is between its existence as a place of business and as a place of residence. In Japan, there are multitudes of micro enterprises managed by self-employed people, and in reality, those enterprises are more like private groups than business entities. As business and everyday life are closely interconnected at micro businesses, the SME policy covers some matters that should in principle be addressed by social policy.

The third factor is a political one. From the policymakers' viewpoint, it is easy to gain the public's support for assistance for SMEs. It also suits policymakers that direct fiscal expenditure can be kept small because financial and taxation relief account for most of the current support measures for SMEs.

Of course, preferential tax breaks aggravate the government's fiscal situation by reducing tax revenue, while financial relief may lead to a higher fiscal burden in the future if borrowers receiving the relief go out of business. However, at a minimum, fiscal and tax relief measures do not entail direct fiscal expenditure at the time of implementation, and therefore, it is easy to pass them through a budget formulation process. The SME policy is a clever scheme that brings benefits to a wide range of companies while allowing everyone, including those who are involved in political, administrative and fiscal affairs, to avoid the sense of bearing more of a burden.

♦ ♦ ♦

It is difficult to fundamentally change the SME policy, which involves the complex web of factors described above, but it is essential to change the current trend of declining vitality of the SME sector.

Japan, with its mature economy, must take the path of taking risks and exploring new markets, and the SME sector should play the central role in that effort. To that end, it is necessary to promote economic dynamism while unraveling the complex web of factors. The term "dynamism" may easily evoke the specter of business closure and the ensuing disruptions to life. However, if the process of support leads to enough new businesses being started or re-invigorated, the public's perception of economic dynamism is likely to change.

The ongoing COVID-19 crisis could become a major turning point. The provision of financial aid for eating and drinking establishments complying with requests for reducing opening hours under the declaration of a state of emergency has supported many small establishments, but on the other hand, it has widely raised awareness about the problems involved in the method of offering across-the-board support in order to allow for the continuation of business. Many business owners are considering exploring new fields of business or switching to different business sectors with an eye to a post-COVID-19 world. If they choose either of those options, that may be regarded as a business opening in the broad sense of the term, regardless of whether they close their doors or maintain their existing companies.

Measures to encourage such activities have already been prepared. Under the third supplementary budget for fiscal year 2020, a subsidy program for business restructuring intended to overcome the COVID-19 crisis has been introduced, and for the moment, it is important to make full use of this and other existing measures. If the subsidy program is found to be inconvenient for users, the government may consider strengthening support by enlisting people with practical experience. In the long term, a fundamental review of the definition of SMEs is necessary. Among the measures to be considered will be the revision of the capital amount standard, which has kept SMEs undercapitalized and made it difficult to carry out business restructuring through share transfer, and more detailed classification of companies by size.

I cannot ignore the feelings the feelings and struggles of those who are barely managing to keep their businesses afloat or the significance of measures to support them. All that I would like to point out is that implementing support measures intended to encourage business owners to close their businesses or start new ones depending on their own circumstances and judgment is also a promising option. As prospects for an exit from the COVID-19 pandemic remain dim, the adverse situation for SMEs is expected to continue. We are at a crossroads of whether we can change course away from continuing across-the-board protection and towards promoting economic dynamism.

* Translated by RIETI.

May 14, 2021 Nihon Keizai Shimbun