Japan ranks 120th among 156 countries in terms of its gender gap, with women earning significantly less than men. This column uses survey data to investigate the employment and earnings dynamics of women in Japan over their life-cycle, and finds that tax exemptions and social insurance benefits for low-income spouses significantly dampen women’s labour supply and earnings. There is a significant room to improve women’s participation and earnings by removing the fiscal policies that disincentivise work and skill accumulation. The policy changes would also mean that the government could raise more tax revenues without causing a welfare loss.

Some policies could act as barriers to women’s labour supply, holding back their income growth, and preventing an economy from utilising its full capacity (Borella et al. 2019, Doepke and Tertilt 2008).

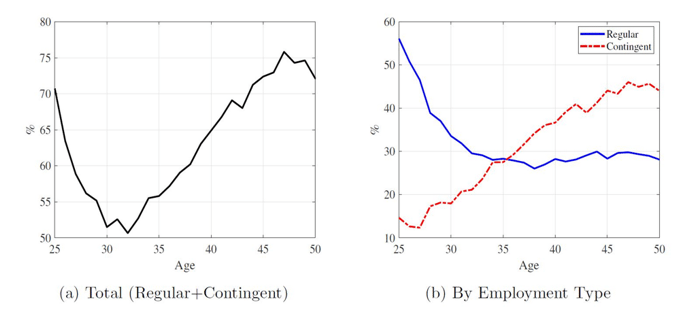

In Japan, women's earnings are significantly lower than men's. Using individual data from the Japan Panel Survey of Consumers (JPSC), we track the labour market experience of women born in the 1960s through 2018 and analyse their employment and earnings dynamics (Kitao and Mikoshiba 2022). As shown in Figure 1(a), women’s labour participation rates exceed 70% in their mid-20s, but declines to 50% in their early 30s, followed by a gradual increase.

The Japanese labour market is characterised by a two-tiered employment system, which consists of regular and contingent employment. On average, regular jobs are more stable and pay much more than contingent jobs, while the latter include part-time and temporary jobs, and dispatched labour, often based on fixed-term contracts. As Figure 1(b) shows, the decline in the labour participation rate of women until their mid-30s is explained by the fall in the number of regular employees, while the increase after their 30s is explained by the rise in the number of contingent employees.

[Click to enlarge]

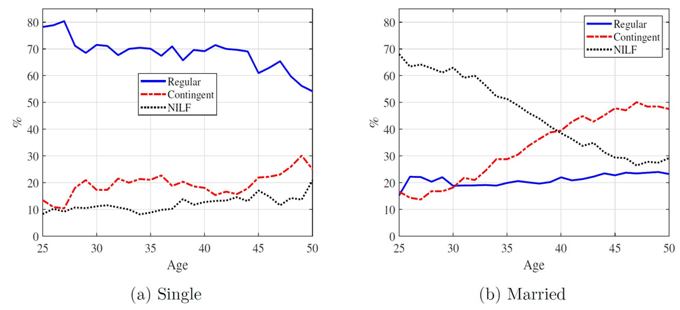

Figure 2 shows that there is no significant change in the share of regular employees within a group of single women or that of married women. The overall decline in the share of regular workers is explained by the change in employment status at both marriage and child-bearing ages.

[Click to enlarge]

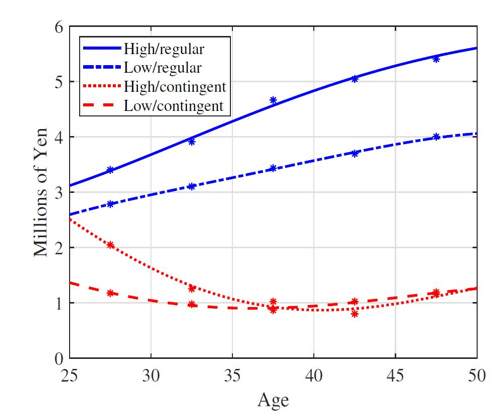

Earnings of contingent workers are significantly lower than those of regular workers as shown in Figure 3. Moreover, earnings of contingent workers do not grow with work experience and the profile remains flat over the life-cycle.

We construct an overlapping generations model that explains the pattern of women's labour force participation and the wage structure. We use the calibrated model to analyse the roles of fiscal policies that are meant to support low-income spouses, and study how they affect work incentives of women at different stages of their life-cycle and their economic wellbeing.

Our model allows single and married women at different stages of their life-cycle to choose both whether to participate and the type of employment (either regular or contingent). Women accumulate human capital on the job, and the growth of earnings depends not only on their age, education level, and their current employment, but also on the employment decisions they make over the life-cycle.

We focus on the effects of the three fiscal policies: spousal deductions, exemptions from the social insurance premiums, and survivors' pension benefits. Dependent spouses – in nearly all cases married women – are entitled to these benefits subject to earnings thresholds that vary by policy.

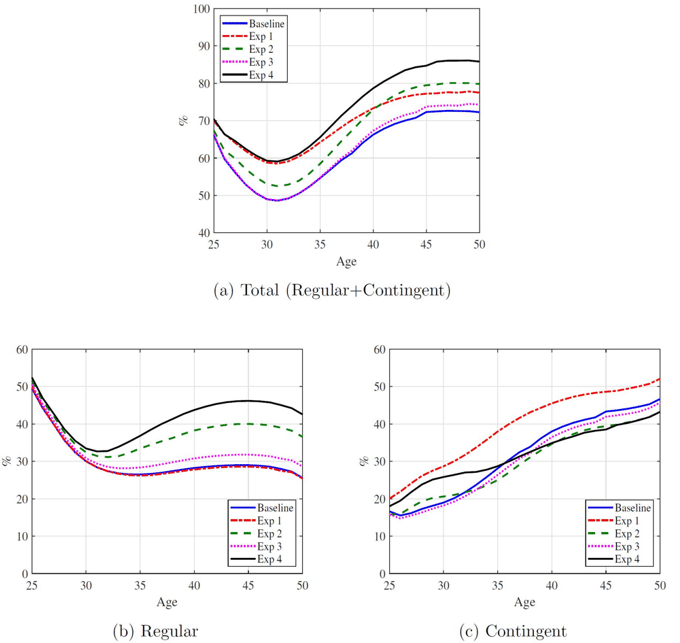

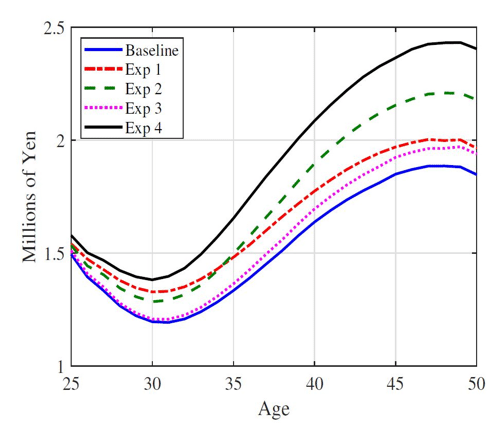

The quantitative results show that all three policies suppress women's incentives to work and accumulate skills and lower their life-time earnings. Figures 4 and 5 show the changes in women’s participation rates and earnings over the life-cycle, comparing the outcomes in the baseline economy and alternative scenarios.

[Click to enlarge]

The average participation rates of women aged 25 to 64 increases by 6.5, 6.6 and 1.3 percentage points if we remove spousal income tax deductions, social insurance premium exemptions, and survivors’ pension benefits, respectively. Similarly, the average earnings of women increase by 7.0%, 16.3%, and 4.1%, respectively. The removal of the first two policies causes a major rise in the participation rates of a similar magnitude, but the effects on the average earnings are very different. Without spousal deductions, many women choose to participate but they continue to keep their earnings at a lower level to avoid paying social insurance premiums, which amount to around 15% of their earnings. Therefore, any increase in the participation rates is entirely due to an increase in the number of low-income contingent workers, which results in a smaller change in earnings compared to the removal of exemptions from payment of social insurance premiums. The latter causes women to shift from non-participation in the labour force and contingent jobs to regular jobs, which generates a large increase in their average earnings as they accumulate more human capital during regular employment. Although policy changes raise the tax burden on women under all policy experiments, the higher earnings of more productive women raise the average consumption and improve welfare when the government transfers back additional net tax revenues to them.

If the three policies are removed altogether, women’s participation rates rise by 13 percentage points, and they earn 28% more on average. They also pay 20% more to the government in taxes and social insurance premiums on their higher earnings. Average consumption of women increases by 3.0% and they enjoy a welfare gain of 2.1% in consumption equivalence.

Our findings suggest that there is a significant room to improve women’s participation and earnings by removing the fiscal policies that disincentivise work and skill accumulation. Moreover, the policy changes would mean that the government could raise more tax revenues without causing a welfare loss.

The policies that were introduced to support the lives of spouses with zero or low incomes functioned well in an old economy where the norm was that women stayed at home and men worked. These policies now present a significant detriment to women's labour force participation, productivity and wage growth. Japan faces a severe shortage of workers and a rising fiscal burden that accompanies the financing of social security expenditures for the elderly over the coming decades. It is critical to remove obstacles that are preventing women from participating in the labour market and engaging in jobs that fully utilise their skills.

Editor’s note: The main research on which this column is based (Kitao and Mikoshiba 2022) first appeared as a Discussion Paper of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) of Japan.

This article first appeared on www.VoxEU.org on March 30, 2022. Reproduced with permission.