There is growing interest in measuring the scientific aspects of industrial innovation and performance to understand the economic impact of publicly funded R&D. This column presents new indicators for science-industry linkages in Japan based on a novel dataset combining academic research paper data, patent data, and economic census data. It finds that the academic sector is getting more involved in patenting activities, and that scientific knowledge generated in the sector is being utilised not only in science-based industries, but also in many others.

A scientific foundation has become increasingly integral to the industrial innovation process. For example, genome science has substantially changed the research and development (R&D) process of the pharmaceutical industry. Miniaturisation of the large-scale integrated circuit fabrication process requires an understanding of the nano-level physicality of its materials. Furthermore, advancements in information technology have a significant impact on society and the economy. In particular, ‘big data’ analysis contributes to the scientific understanding of business and management activities (Redding and Weinstein 2016). Since science sectors, such as universities and public research institutes, are heavily subsidised by public money, there is a growing interest in measuring the scientific aspects of industrial innovation and performance to understand the economic impact of public R&D, despite severe constraints on public spending in general. Against this background, in a recent paper, we propose new indicators of science-industry linkages that reflect the interaction between science and industry via academic patenting activities (Ikeuchi et al. 2017).

Traditionally, the degree of scientific basis, or ‘science intensity’ of industry has been measured using non-patent literature citations made by patents (Narin and Noma 1985, Schmoch 1997). This indicator captures the extent to which patents (technology for industrial use) are based on the scientific content of research papers. Alternatively, the science-technology linkage can be captured using patent-publication pairs, i.e. overlapping content regarding the research output/invention between patents and research papers (Lissoni et al. 2013, Magerman et al. 2015).

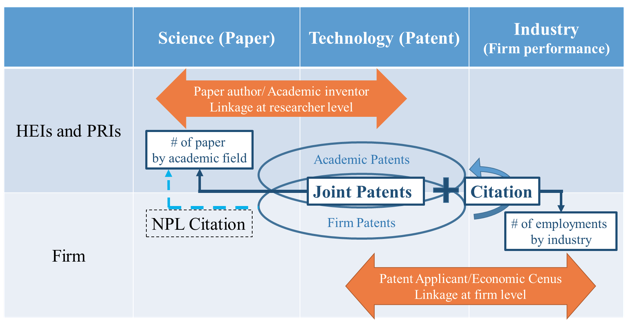

Both of these indicators reflect only one aspect of science linkages—non-patent literature citations show the degree of disembodied scientific knowledge that flows into patents, while the patent-publication pair indicates co-occurrence of scientific and invention activities within the same research. Our proposed new indicators of science-industry linkages can capture the linkage between science and technology embodied in human capital (academic inventors) via patenting, and the indicators are based on a novel dataset combining science (academic research paper data), technology (patent data), and industry (economic census data) at the author/inventor and firm levels to see how academic discipline, technology, and economic activities are interlinked.

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between the dataset and the indicators. While the non-patent literature citations of patents are based on a firm's patent citations of scientific publications in the academic sector, our new indicators for science-industry linkage capture the interactions between the industry and the academia in patenting activities, i.e. joint inventive activities (captured by joint patent inventions) and firms' patent citations to academic patents.

Both industry citations to the academic inventors' patents and the joint patent inventions between firms and such academics reflect different channels of scientific knowledge flow from academia to industry compared to those measured by conventional indicators such as non-patent literature citations in patents. Furthermore, unlike past studies regarding paper-patent linkage at the researcher level for particular technologies, such as biotechnology (Murray 2002) and nanotechnology (Meyer 2006), our dataset covers all technological fields by constructing a large-scale database.

Our new indicators are intended to capture the mechanism of involving scientific knowledge in industrial innovation via patenting activity of academia. Although universities and public research institutes principally provide scientific publications as their research outputs, there is a growing global trend of patent applications from these institutes (OECD 2013). In Japan, national universities, which used to be government organisations, became independent agencies in 2004. This institutional reform allows them to claim patent rights, and university patent applications have increased significantly (Motohashi and Muramatsu 2012). Therefore, a patent-based science linkage indicator has become increasingly important.

Academia-industry interactions via patenting in Japan

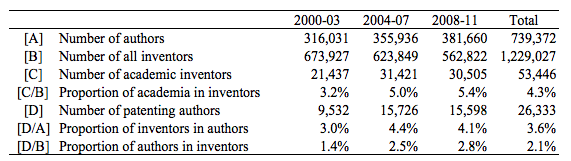

According to our dataset, as shown in Table 1, the proportion of academia among inventors increased in Japan from 3.2% in the period 2000-03 to 5.4% in the period 2008-11. The proportion of academic authors with patent inventions also increased from 3.% in 2000-03 to 4.1% in 2008-11. Furthermore, the proportion of academic authors to total inventors doubled from 1.4% to 2.8% during the 12-year period.

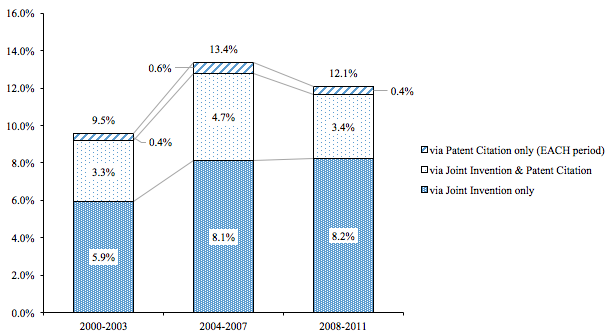

Figure 2 shows the aggregated trend of academic involvement in industry innovation. It shows that both the shares of academia-industry joint applications and patents citing academic patents increased from 2000-3 to 2004-7. In subsequent periods (2008-11), the share of joint applications increased further, while the share of patents citing academic patents decreased. Additionally, the number of inventors per employee (reflecting R&D intensity) decreased over time in the industry sector.

New indicators of science intensity of firms

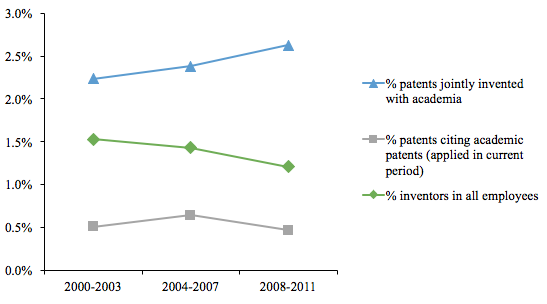

We define science intensity as the amount of new scientific knowledge (the number of academic papers) utilised by inventors in firms through joint inventions with academia and/or academic patent citations per employee in industry. Figure 3 shows the science intensity in the total economy in Japan, which increased from 2000-3 to 2004-7 by increasing both joint inventions and academic patent citations. After the incorporation of Japan's national universities in 2004, academic patent applications increased substantially. Moreover, industry-university collaboration activities have been promoted for over ten years, which has contributed to the increase in science intensity indicators after 2004.

(Average number of linked academic publications per 100 employees)

However, the total science intensity decreased from the second to the last period. Along with the incorporation of the national universities in 2004, the research outputs of the universities sufficiently valuable for patent applications were intensively patented, and, accordingly, patent citations to academic patents temporarily increased sharply in 2004-7. For that reason, in the last period, research outputs suitable for patenting at university might have been exhausted. The decline in joint research may be influenced by the fact that firms saved R&D investment due to the recession after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008.

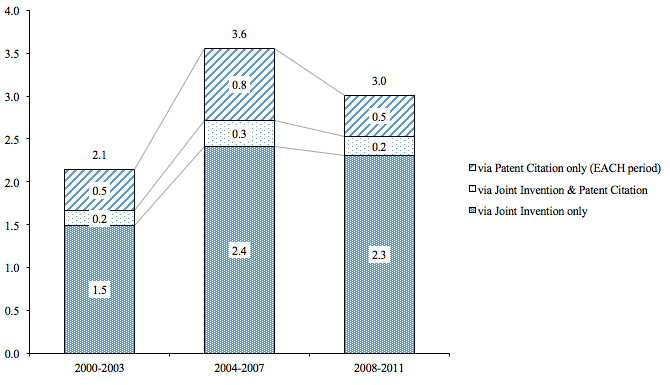

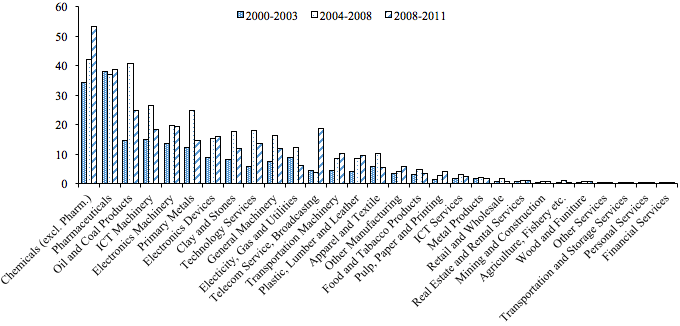

Figure 4 shows the industry breakdown of employee-based science intensity. It shows that the chemical and pharmaceutical industries substantially lead other industries. However, the science intensity indicator has generally increased in other industries, which means that ‘scientification’ of industrial innovation can be observed across industries. In general, the cross-industry distribution of science intensity becomes equal.

(Average number of linked academic publications per 100 employees)

Utilisation rate of science knowledge

We also defined an indicator from the viewpoint of science as a utilisation rate of science-knowledge of academic research by industrial inventors, via joint invention with industrial inventors and/or citations by industrial patents to academic patents. Figure 5 shows the aggregated trend of this indicator. A similar trend is observed in the employee-based science intensity, which increased from 2000-03 to 2004-07 and decreased in the subsequent period. The changes in the utilisation rate of science-knowledge are caused not only by the demand side factors of scientific knowledge in industry, but also by the supply side factors of scientific activities. The up-and-down trend of the utilisation rate of science-knowledge is similar to that of employee-based science intensity, but it should be noted that any changes in supply-side factors such as new scientific advancements may affect the trend.

(Share of academic publications linked to industry in total academic publications)

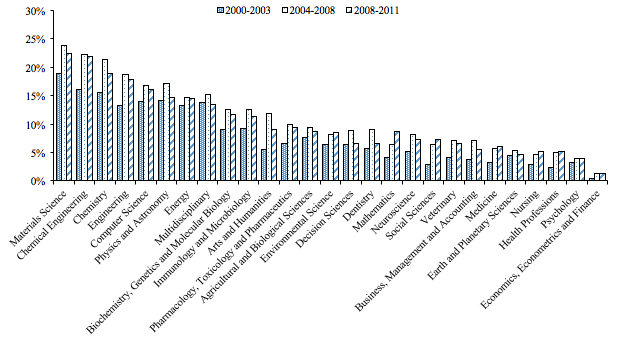

Viewing this trend from an academic perspective, the situation is more complicated. In general, as shown in Figure 6, the industry utilisation rate increased over time, while a sharp decline from 2004-7 to 2008-11 is found in some fields (e.g. chemistry, physics, and astronomy). In contrast, some academic fields, such as mathematics and social science, show a strong increasing trend. Thus, the overall inequality in URSK in the academic field decreases from 2000-3 to 2008-11.

(Share of academic publications linked to industry in total academic publications)

Discussion and conclusion

In this column, we have presented new indicators to measure scientification of industry in Japan, by linking a scientific paper database (science), patent information (technology), and economic census data (industry). The new indicators reflect a mechanism of science linkage between science and industrial activities, which cannot be measured by the existing indicators based on non-patent literature citations.

These new indicators of science linkage in Japan show an increasing trend over the past ten years. One reason behind these trends is the institutional reform of the academic sector in Japan, i.e. incorporation of national universities in 2004 and various polices stimulating university-industry collaborations from the late 1990s onwards (Motohashi and Muramatsu 2012). These policy actions induced academic sectors to work with industry, which involved patenting activities.

Moreover, the growing importance of scientific inputs in industrial innovation has an impact as well. In our analysis, science linkage with industry is found not only in science-based industries, such as pharmaceuticals and electronics, but also in many other industries. Our study has shown that scientific knowledge becomes general inputs in almost all industries, and this trend can be referred to as the ‘science-based economy’, for non-science based industries as well.

Editors' note: This column is based on a research project conducted as a part of the Empirical Studies on ‘Japanese-style’ Open Innovation project undertaken at the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI), and the result of a joint research project of the National Institute of Science and Technology Policy (NISTEP) and RIETI.

This article first appeared on www.VoxEU.org on June 28, 2017. Reproduced with permission.