Current IoT trend is limited to Tokyo

I often travel to regional cities to give lectures. Let me share some episodes from my experience. When I went to Sapporo, I asked the organizer how many people would attend an Internet of Things (IoT)/Industrie 4.0 seminar in the city. The organizer had never heard of a seminar of such a theme in Sapporo and did not think anyone would come. The organizer was stunned when I said that a seminar of this kind would easily attract 500 people in Tokyo, adding that such a seminar by Hitachi's CEO and another by GE's Japan representative gathered 1,000 and 3,000 people respectively.

After a seminar in a regional city, I was interacting with participants on IoT, and one of them revealed that companies in that region were keeping low key on the matter, hoping that the storm of IoT trend would go away soon. A senior official of a regional local government told me that when he shared information about IoT that he learned in Tokyo with his colleagues, those around him worriedly said that he should not believe in fabricated stories from the big city.

Judging from my experiences, today's IoT trend is limited to the Kanto region, or Japan's three major metropolitan areas at best. Unless we act now, large corporations in Tokyo will end up being the only parties that embrace IoT. With its limited nationwide introduction, the Shinzo Abe administration's ambition of achieving IoT-based productivity revolution as one of its new three arrows of Abenomics might become a mere dream that never comes true.

Yet, we have lived through the time of transition that started from the introduction of personal computers in offices and their eventual connectivity to the Internet. Today, computers and the Internet are a normal part of everyday business. Those who were afraid to touch computer keyboards have been transferred and disappeared from the business frontline. The tide of Internet technologies engulfing various fields across the world is not something we should avoid by simply staying low key. We must keep up with the Internet trend or risk being left behind from the rest of the world.

IoT delivers the greatest impact for SMEs and agriculture

Since large corporations have already pursued operational efficiency of, investing a lot of money to introduce an IoT system would only improve their productivity by certain percentages . Newspaper articles cite such figures of productivity improvement as 20% by Fujitsu Ltd., 30% by Omron Corporation, and 50% by Komatsu Ltd.

However, introducing IoT to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and agricultural operators that have not worked on operational efficiency could boost productivity by several times over with a modest investment of several million yen.

Most successful SME and agricultural examples in Japan: Case of Asahi Shuzo in Yamaguchi Prefecture

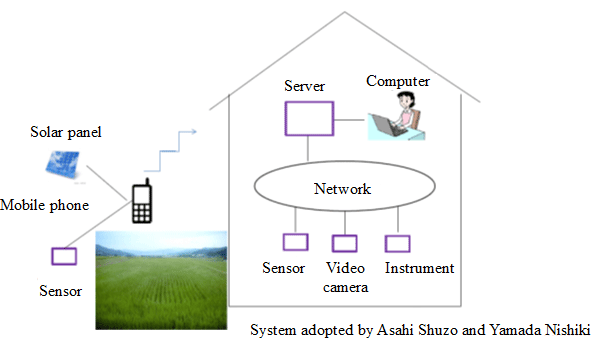

Asahi Shuzo Co. Ltd. was once the fourth-largest sake brewery in Yamaguchi Prefecture. However, when the company encountered a business downturn, its master sake brewers jumped ship. Company president Hiroshi Sakurai was always skeptical about the master brewers' secretive stance on sake brewing know-how, and when they deserted the company, he decided to embrace a "science backed with logic and data" brewing philosophy. He installed sensors, video cameras, and measurable instruments at every step of the brewing process within the plant to collect data, and began producing sake according to the logic of tasty sake brewing. The result was top quality sake. The approach also stabilized its quality and production volume, enabling the launch of mass production. Its product "Dassai" is sold for over 30,000 yen per 720ml bottle and was gifted by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to U.S. President Barack Obama when he visited Japan in 2014. The company's sales for the fiscal year ending in September 2014 jumped by 26% year-on-year.

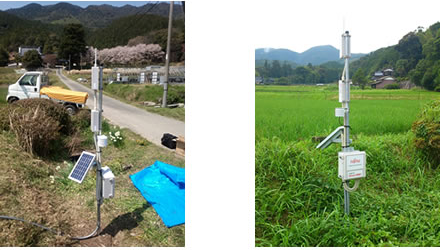

In order to provide a stable supply of premium-quality Japanese sake, it is also necessary to ensure a stable supply of the key ingredient, Yamada Nishiki rice. For this reason, the company installed sensors in their paddy fields. Air temperature, humidity, soil temperature, and soil moisture content are measured every hour and sent via mobile phones for status management. Any deficiency of nutrients is detected and fertilizer is immediately applied to the paddies.

Below is the schematic diagram of the system adopted at the site. This is a simple system that even SMEs could easily supply and adopt.

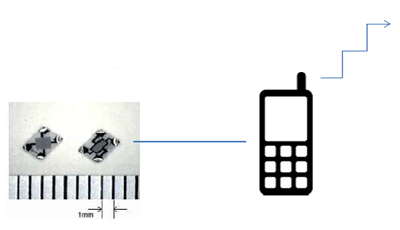

As you can see, to put it simply, an IoT system can be set up with just a single sensor and a single mobile phone. The amount of investment necessary would be less than one million yen. Yet, this has the potential of dramatically increasing company sales.

For product items that are subject to market liberalization under the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) with a potentially major impact, it is crucial to act now and reinforce their industrial competitiveness. The IoT could be a key means of achieving this objective.

From my experiences

This is rather personal, but I grew up in a single-parent family in a depopulated town of just 9,000 people. Having been born to a farming family, I used to do farming chores such as rice planting and harvesting in muddy rice paddies until I left home and started university. My mother used to tell me not to take over the farming business and instead study hard and attend a university in this day and age. I was forced to study despite my aversion. After graduating from university, I found a job in Tokyo. Having observed carefully the lifestyle of Tokyoites, I long contemplated the state of Japanese agriculture, in which parents have to dissuade their children from taking over the family business. Some 30 years after leaving my hometown, I finally came to a conclusion.

My conclusion is that Japanese agriculture has no future unless it adopts a structure that would attract ordinary young people.