The period since COVID-19 appeared in January 2020 has been labeled the megacrisis period. The pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine War, volatile oil and food prices, the Trump trade war, exchange rate fluctuations, and other factors have buffeted the world economy. How have these factors affected Japanese inflationary expectations?

Rising oil and food prices, a weakening yen and other factors can raise the inflation rate. The Bank of Japan (BoJ) has been attempting to increase inflation at least since Haruhiko Kuroda became head of the BoJ in March 2013. In April 2013 the BoJ implemented quantitative and qualitative monetary easing, significantly increasing the monetary base. In January 2016 it instituted negative interest rates and in September 2016 it introduced yield curve control by targeting short and long-term interest rates. The BoJ abandoned negative rates on the uncollateralized overnight call rate in March 2024. It raised its target for overnight interest rates to 0.25 per cent in July 2024 and to 0.5 per cent in January 2025.

How have inflationary expectations responded to shocks from rising commodity prices, yen depreciations, BoJ monetary policy, and other factors? One way to investigate this is to look at how assets that are harmed or helped by inflation have fared. If investors expect more inflation in the future, they would purchase assets that benefit from inflation and sell assets that are harmed by inflation. This would raise the prices of assets that gain from inflation and harm the prices of assets that are exposed to inflation.

To investigate how assets are impacted by inflation news I regressed stock returns for 86 Japanese sectors on a measure of expected inflation and on other variables. To calculate expected inflation, I used data from Japanese 10-year inflation-indexed government bonds. The difference between the yield on Japanese 10-year government bonds and Japanese 10-year inflation-indexed government bonds provides a measure of expected inflation. This measure also contains compensation that investors require for inflation risk. When this difference, called the breakeven rate, increases, it means that investors anticipate higher inflation over the next ten years.

I thus regressed returns on 86 sectors on the change in the breakeven rate, the change in the log of crude oil prices, the change in the yen/dollar nominal exchange rate, and other variables over the 1 January 2013 to 12 March 2025 period. This provides regression coefficients (betas) for how 86 sectors are affected by inflationary news.

Assets with positive betas to the breakeven rate represent assets that benefit as investors expect higher inflation. Assets with negative betas to the breakeven rate represent assets that lose as investors expect higher inflation. If investors expect higher inflation over the next ten years, they will respond by purchasing assets with positive betas to the breakeven rate and selling assets with negative betas to the breakeven rate. This will increase returns for assets that benefit from higher inflation and lower returns for assets that are harmed by higher inflation. There should thus be a positive relationship between assets’ returns and their breakeven betas when investors expect higher inflation and a negative relationship when they expect lower inflation.

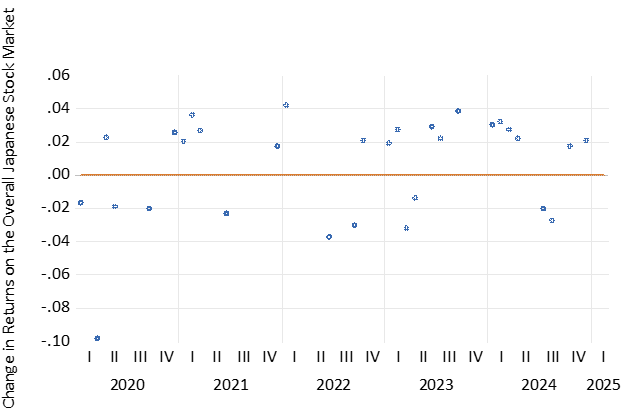

For every month between January 2020 and March 2025, I regressed returns on the 86 assets on their breakeven betas. To facilitate interpretation, I calculated how changes in the breakeven inflation rate affected returns on the overall Japanese stock market. An increase in the breakeven inflation rate increases returns on the overall stock market. Figure 1 shows the results.

The figure indicates that, before October 2022, investors expected higher inflation (which raised Japanese aggregate stock returns) in some months and lower inflation (which lowered Japanese aggregate stock returns) in other months. In March 2020, when news of the COVID-19 pandemic hit markets, expectations of lower inflation caused the Japanese stock market to fall almost 10%. Starting in October 2022, however, investors expected higher inflation, which raised stock returns in 12 months, and only expected lower inflation in 4 months. This indicates that investors anticipated higher inflation much more often than lower inflation since October 2022.

These results indicate that an inflationary mindset is taking hold in Japan. Current BoJ Governor Kazuo Ueda is pursuing what he calls “good inflation.” This occurs when inflation is driven by wage increases that increase consumer spending and aggregate demand. The rise in spending then in turn raises prices and wages, generating a virtuous cycle. Wages increased 5.1 per cent in the 2024 spring wage offensive and 5.5% in the 2025 spring wage offensive. Firms are also abandoning their reluctance to raise prices. Thus good inflation in Japan may be within reach, and the BoJ may be able to normalize monetary policy.

The Japanese government should remember that what ultimately matters for consumers’ welfare is the real wage, that is, the money wages received corrected for inflation. The real wage depends on labor productivity. One way to boost productivity is to use technology. According to a survey of over 10,000 Japanese people conducted by the Nomura Research Institute, only 9% had used generative artificial intelligence (AI). Japan could increase interest in AI by encouraging middle and high school students to experiment with it. They could also provide AI training for workers through university extension programs, research institutes, and other sources. If more workers used AI, it would boost their productivity.

Government initiatives to raise wages that do not increase productivity will strain firms’ finances. This represents a heavy burden for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). SMEs often cannot pass on higher labor costs to their customers. The government should focus on alleviating these difficulties through tax breaks, subsidies to increase productivity, and other instruments.

As the BoJ normalizes policy, interest rates will rise. The government should remember the dangers to public debt sustainability that come with higher interest rates. The Japanese gross public debt equals 250% of GDP and its net debt exceeds 170% of GDP. Higher interest rates raise the cost of servicing the debt. Debt service costs in 2025 are forecasted to be above 4 per cent of GDP and higher interest rates will raise these costs further. The government should therefore remain vigilant to whether higher interest rates generate unfavorable debt dynamics.