Active Implementation of Industrial Policy and Economic Analysis

In recent years, major countries have been actively implementing industrial policies. In Japan as well, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) started to advocate the "Mission-oriented Economic and Industrial Policy" as the "New Direction of Economic and Industrial Policies" three years ago. According to the IMF's New Industrial Policy Observatory (NIPO) database, which records announced or implemented industrial policies around the world, waves of new industrial policies have arisen mainly in advanced countries and subsidies are the most frequently used policy instrument (Evenett et al., 2024).

The scope of industrial policies is very wide. I teach a section on industrial policy, or policies targeting industries and companies, within a graduate school class titled "Introduction to Evidence-based Policymaking (EBPM)," covering such topics as R&D grants and tax incentives, corporate taxation and financial assistance, regulations and competition policies, corporate governance systems, industrial location policies, and trade policies.

Papers that survey research on a wide range of industrial policies include Pack and Saggi (2006), Harrison and Rodríguez-Clare (2010), Juhasz, Lane, and Rodrik (2024) (Note 1). These papers universally point out, although with some differences in nuance, that industrial policies are theoretically justified when there is a market failure, such as externality, learning effect, or coordination failure. On the other hand, research that clarifies the effectiveness of industrial policy based on causal analysis is limited and empirical evaluations are far from reaching a consensus. Juhasz, Lane, and Rodrik (2024) point out that industrial policies are based on economic grounds and state that national governments should consider industrial policies focused on productivity improvements in the services industry (retail business, service business, medical services, and long-term care services, etc.) and I agree with their view.

This column shifts perspective to introduce what types of companies and workers support industrial policy based on surveys targeting companies and workers. In the field of international economics, there have been many political economic analyses examining the characteristics of individuals who support or do not support, for example, protectionist trade policies (as examples from Japan, Ito et al., 2019; Tomiura et al., 2019). Similar studies on income redistribution policies have also been frequently undertaken (e.g., Ohtake and Tomioka, 2004). However, I have not found research that specifically covers the characteristics of companies and workers that support industrial policy as a whole. Such research is different from evidence-based policy making research, but understanding the characteristics of potential supporters and opponents could prove beneficial in designing and planning industrial policy.

Characteristics of Companies Supporting Industrial Policy

In the survey of Japanese companies, respondents were first asked about their awareness of recent industrial policy initiative, and their evaluations of proactive industrial policy by the national government (Note 2). When asked whether they were familiar with the "Mission-oriented Economic and Industrial Policy," which involves the national government playing an active role in strategic investments in growth sectors, 3.2% responded that they "were very familiar," 39.3% responded "had heard the term but are not very familiar," and 57.6% responded "had never heard of it." The low level of awareness may be due to the small number of companies directly targeted by the policy or responses may have differed if questions were broken down to specific policy measures, but in general, it cannot be said that Japanese companies are highly aware of the recent industrial policy initiative (Note 3).

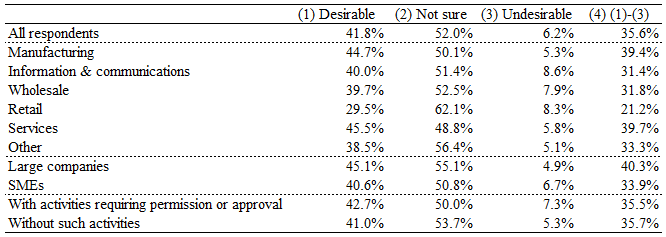

Table 1 shows tabulated responses to the question, "How do you evaluate the government's active implementation of industrial policy?" Companies that responded with "Desirable" accounted for 41.8%, "Undesirable" accounted for 6.2%, and "Not sure" accounted for 52.0%. More than half of the companies were neither for nor against it, but generally, there is an impression that Japanese companies view industrial policy rather positively.

By industry, companies in manufacturing industries and service industries tend to strongly support industrial policy, while companies in the retail industry show relatively weaker support. It is not shown in the Table, but in manufacturing industries, the percentage of companies that responded "Desirable" was considerably high at 52.2% among those in the machinery industry (Note 4). This may reflect the fact that the Japanese government has provided significant support towards implementing a policy to promote domestic production of semiconductors and storage batteries. Other than this, it is also notable that large companies show stronger support for industrial policy than SMEs. No difference is observed between companies that engaged in business activities that require permission or approval and those that do not.

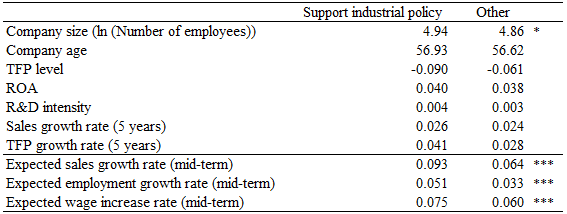

Table 2 compares the characteristics of companies that responded "Desirable" and companies that responded otherwise. There are no significant differences between them in terms of observable corporate performance, such as total factor productivity (TFP), return on assets (ROA), R&D intensity, or past growth rate. It is not shown in the Table, but there is also no difference regarding whether companies have been using tax incentives, including tax cuts on investment or on R&D. However, companies that support industrial policy have stronger expectations for their growth in the coming five years.

In summary of the above data, there is no indication of low-performing or struggling companies supporting industrial policy with the expectation of receiving relief measures. Rather, industrial policy is supported more strongly by companies with higher anticipated growth rates. This tendency may reflect the nature of the recent industrial policies that are focused on growth sectors.

Characteristics of Workers Supporting Industrial Policy

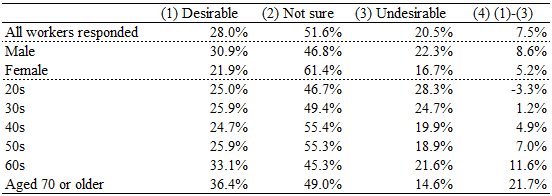

Also, in the recent survey targeting workers, we asked workers how they view industrial policy (Note 5). To enable a comparison with the results of the company survey reported above, nearly identical wordings were used for questions and response options (Note 6). Table 3 shows the tabulated results. Workers who responded "Desirable" accounted for 28.0%, those who responded "Undesirable" 20.5%, and those who responded "Not sure" accounted for 51.6%. In the same manner as in the results of the company survey, more than half of the workers were neither for nor against the measures. Workers who supported industrial policy were slightly larger in number than those who did not, although that tendency was not as notable as in the responses of companies.

In terms of individual characteristics, there is a systematic relationship where support for industrial policy increases with age. It is impossible to discern whether this is simply due to an age effect or is due to a cohort effect. However, workers now in their 60s and 70s were born before the first Tokyo Olympic Games held in 1964, suggesting that the cohort that experienced the rapid growth period characterized by the development of the machinery and chemicals industries may strongly support industrial policy. On the other hand, if this is indeed an age effect, it is possible that support for industrial policy would increase with the increasing age of the working population. Males show slightly stronger support than females, but the gender difference is small. Although it is not shown in the Table, there is no systematic difference by educational background, and difference by industry is also insignificant.

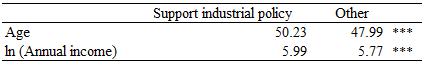

Table 4 shows the comparisons of the average age and average annual income (in logarithmic terms) between workers who responded "Desirable" and those who responded otherwise. There are significant differences regarding age and annual income at the 1% level, and the average annual income for workers who support industrial policy is higher by 24%. Even after controlling for other individual characteristics, such as gender and educational background, age and annual income are factors that have significant explanatory power regarding support for industrial policy.

Conclusion

There is limited understanding of what type of companies and workers support industrial policies, and the findings presented here may contain interesting facts. However, since these surveys were not specifically focused on specific industrial policies, the available information is limited. There is room to expand this study by such means as breaking down policies and asking more detailed questions.

* The surveys of companies and workers and the analysis of the results used in this column were supported by the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (21H00720, 23K20606). For use of the data from METI's "Basic Survey of Japanese Business Structure and Activities," I am grateful to the statistics department of METI.

October 3, 2024

>> Original text in Japanese