Over the last decade, there has been increasing emphasis on the decline in Japan's research capacity, with a fall in the number of students who advance to doctoral courses cited as a factor (National Institute of Science and Technology Policy, 2023) (Note 1). Meanwhile, over the past several years, the government’s Basic Policies for Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform have mentioned plans to nurture and support research talent with doctoral expertise. In particular, the 2023 Basic Policies for Economic and Fiscal Reform stated that in order to realize an environment that encourages competent young people to aspire for a doctoral degree, the government will strengthen support measures, such as: improving the treatment of students in doctoral courses; securing an environment in which the students can dedicate themselves to challenging research programs; and developing career paths that enable workers with a doctoral degree to achieve success in a broad range of fields, including in industrial sectors (Note 2). The fact that the government is promoting those initiatives implies that workers with a doctoral degree are facing an unfavorable labor market situation, but what is the reality?

Research on Wages for Workers with High Academic Achievement

In the United States and Europe, several empirical studies have been conducted with respect to wages for workers with a doctoral degree (e.g., Jaeger and Page, 1996; Walker and Zhu, 2011; Engbom and Moser, 2017). Those studies have shown that the wage level for workers with a doctoral degree is higher than that for workers with a master’s degree. For example, Engbom and Moser (2017), who looked at the situation in the United States, found that the wage level for workers with a doctoral degree is 47% higher than that for workers with a master’s degree.

In Japan in recent years, there have been several studies that compared the labor market outcomes for workers who graduated from graduate school and workers who graduated from undergraduate programs (e.g. Morikawa, 2015; Yasui, 2019; Suga, 2020) (Note 3). According to those studies, workers who graduated from graduate school earn 20% to 30% more than workers who graduated from undergraduate programs (graduate school premium) after controlling for individuals’ characteristics, and the employment rate is also higher for workers who graduated from graduate school. As a result, the rate of return from investments associated with advancement to graduate school—represented by the total sum of tuition fees and lost income during school—is fairly high, ranging from around 10% to 20%. However, there are significant limitations to those studies in that no distinction was made between workers with a master’s degree and workers with a doctoral degree due to data limitation.

This author conducted original surveys (in 2017 and 2021) with Japanese workers that distinguished between those with a master’s degree and those with a doctoral degree. According to calculations based on the data obtained from the surveys, after controlling for individuals’ characteristics, the doctoral degree premium (compared with the wage level for workers with a master’s degree) ranged from 15% to 20% among men and from 40% to 60% among women. However, it would be difficult to draw a definitive conclusion from this study given the limited sample size—the number of samples with a doctoral degree was just over 100 (the number of samples with a master’s degree was around 400) in the surveys in both years, and the number of women with a doctoral degree in particular was only 20 to 30.

High Employment Rate for Workers with a Doctoral Degree after Age of 60

The Employment Status Survey (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications), which was conducted in 2022 and the results of which were announced recently, included some additional survey items whose importance has grown in the recent labor market, such as telework, freelance work, and side businesses, and it also adopted a more detailed academic achievement categorization by subdividing the graduate school category into the master’s degree, professional, and doctoral degree categories. Given the emphasis placed on human capital investment, those revisions were valuable improvements. This survey represents a major structural statistical dataset that captures Japan’s labor market, and its sample size is sufficiently large, covering around 1.08 million people aged 15 or older.

Let us compare the labor market outcomes for workers with a doctoral degree and workers with a master’s degree to the best possible extent based on published datasets. Although some people work while at school, this study looks only at those who have already graduated. The share of workers with a doctoral degree in the total number of samples was 1.0% in the case of men and 0.3% in the case of women, while the share of workers with a master’s degree was 3.9% in the case of men and 1.7% in the case of women.

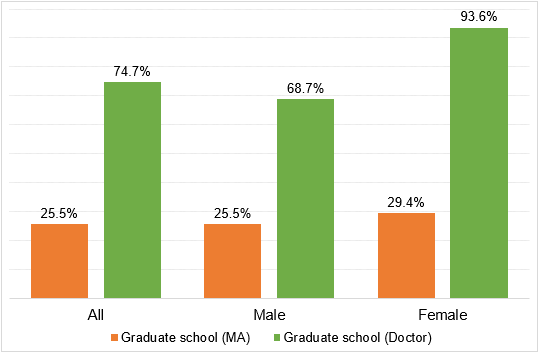

By age group, the employment rate is much higher for workers with a doctoral degree among men who were aged 60 or older. In the case of women, the employment rate was higher for workers with a doctoral degree in all age groups. Among those who were aged 60 or older, the employment rate for workers with a doctoral degree was 6.6 percentage points higher than the rate for workers with a master’s degree for men and 10.1 percentage points higher for women (see Figure 1).

A Doctoral Degree Fetches a High Premium

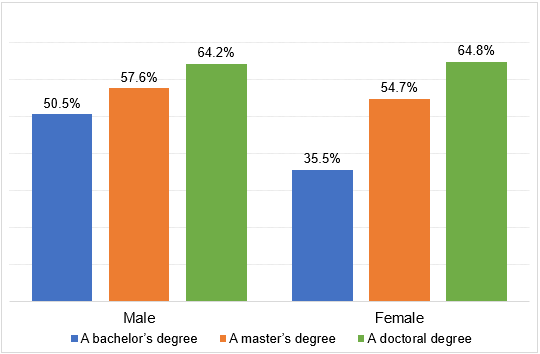

Next, let us compare annual income from work. The comparison is made through a simple WLS estimation using the numbers of samples by the gender, age, and academic achievement categories as weights and annual income (expressed in terms of the logarithm value of the mean value in each category) as the dependent variable (Note 4). The results show that after controlling for age, the doctoral degree premium (compared with the income level for workers with a master’s degree) is 43% for men and 64% for women (see Figure 2) (Note 5). When occupation (broad classification) was added as a controlling variable, the doctoral degree premium was 38% for men and 49% for women (Note 6).

A rough estimate of lifetime income that takes employment probability into account can be obtained by adding up income earned while in each age group, calculated by multiplying the employment rate for the age group by annual income (Note 7). According to the estimation, the average of the lifetime income of workers with a doctoral degree was 31% higher compared with workers with a master’s degree for men and 57% higher for women. In terms of the present value of lifetime income calculated at a discount rate of 3%, the doctoral degree premium was 16% for men and 31% for women. In other words, although advancing to a doctoral course means three years’ worth of lost income, workers with a doctoral degree earn a fairly high income over their lifetime even when that loss is taken into account. The doctoral degree premium in Japan is in no way small compared with the findings of foreign studies. On average, advancing to a doctoral course is an effective human capital investment, particularly for women.

The distribution of workers with a doctoral degree by industry and occupation is very different from the distribution of workers with a master’s degree.

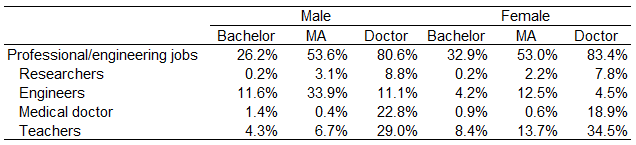

By industry, “school education” and “medical services” together accounted for 60% of the total sample number for men and 68% for women. By occupation, the share of those engaged in professional and engineering jobs was very large. That is a natural result given the high level of skills possessed by workers with a doctoral degree. According to a more detailed classification, “researchers,” “doctors,” and “teachers” together accounted for slightly over 60% of the total number of employed people with a doctoral degree (see Table 1).

Regarding workers engaged in professional and engineering jobs, the doctoral degree premium was 44% for men and 74% for women. Regarding workers engaged in other categories of jobs (e.g., management, clerical, and production process jobs), the doctoral premium was 39% for men and 48% for women. Regardless of the occupation category, workers with a doctoral degree earned higher income than workers with a master’s degree.

Unfortunately, in the publicly available data, annual income can be identified only by broad classification of occupation. “Researchers,” “doctors,” and “teachers” are all included in the “professional and engineering jobs” category. As a result, studies based on published data cannot conduct a comparison between workers with a doctoral degree and workers with a master’s degree based on a more disaggregated classification of occupation. While it is desirable to conduct a more detailed analysis using micro data, the conclusion that would be arrived at through such an analysis is unlikely to be fundamentally different.

Closing Remarks

Of course, among workers with a doctoral degree, there are some who are non-standard workers (10% of men and 24% of women) and some whose annual income is less than 3 million yen (10% of men and 33% of women). Therefore, it is desirable to encourage industries to increase the employment of workers with a doctoral degree as standard full-time employees. It is also important to use scholarship programs and fellowship programs like the Research Fellowship for Young Scientists of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science to support competent students who cannot advance to a doctoral course due to financial constraints. However, as far as we can see from data available from the Employment Status Survey (2022), at least on average, it cannot be said that workers with a doctoral degree are facing an unfavorable labor market situation. Rather, the labor market outcome for them is successful. I look forward to increasing numbers of competent young people aspiring to advance to a doctoral course.

September 5, 2023

>> Original text in Japanese