The UK government has been reinforcing its initiatives toward improving the productivity of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). This column will describe the current status of productivity in the UK and the policy package which was incorporated into the FY2019 UK government budget. This column also intends to touch upon the author's involvement as a researcher in shaping the policy package, as an example of evidenced-based policy making (EBPM).

1. The productivity puzzle in the UK and UK government initiatives

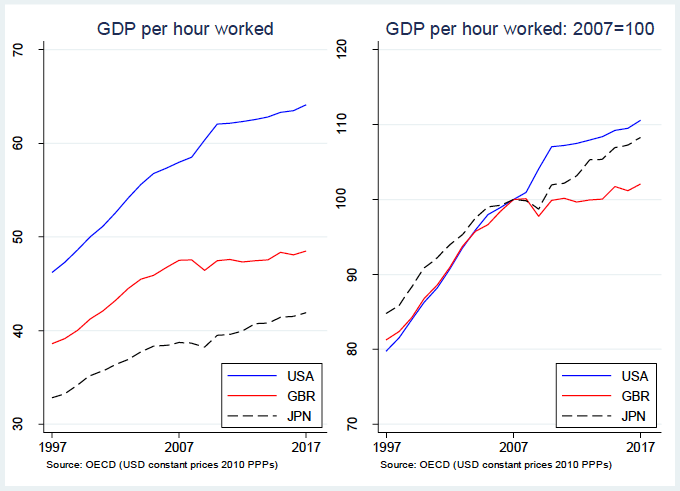

In recent years, increasing productivity has been a common policy task for the major industrialized countries. Since the financial crisis in 2008, the slowdown in productivity growth had been particularly marked in the UK relative to other countries. This "productivity puzzle" has become a major concern for policy-makers, the media and researchers alike. The panel on the left in Figure 1 compares the labor productivity (GDP per hour worked) of the U.S., the UK and Japan. The U.S. has the highest labor productivity and Japan has the lowest productivity, which has been the familiar pattern for quite some time. The panel on the right in Figure 1 has indexed the productivity of each country based on the productivity levels of 2007. Prior to 2007, there were no major differences in the growth rates of labor productivity among these major countries, but since the financial crisis, it is evident that while the level of Japan's productivity remains low, productivity growth is comparable to that of the U.S. Please refer to Morikawa (2018), Miyagawa (2018) and Shirai (2004) for details on productivity theory/problems in measurement.

Turning our attention to the UK, it is evident that the growth rate of the UK's labour productivity has been particularly low since the financial crisis. The UK government has pursued initiatives toward raising productivity. These initiatives focus particularly on the policy package aimed at improving the "long tail" of low-productivity businesses. In the budget draft announced in October 2018, Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond delivered a £31m policy package comprising, among other items, (1) Provision of management training including business schools to 2,000 SMEs; (2) Reinforcement of regional peer-to-peer networks; and (3) Mentoring programs in which senior management of large businesses mentor managers of SMEs. While the policy package, at first glance, appears to be quite ordinary, given that there will likely be a time lag before the effects of policies manifest themselves, it is necessary to continuously implement policies that are similar to those implemented in the past. In any case, the question that arises is why should management support be provided to the "long tail" of low-productivity businesses? As this reflects the result of research in which the author was involved, this column hopes to shed some light on the details and the policy-making process.

2. Draft of the FY2019 Budget: Policy-making process and utilization of research results

Why provide management support to the "long tail" of low-productivity businesses? The discussion's starting point was presented by the draft delivered by the HM Treasury (HMT) and the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS). In May 2018, HMT/BEIS published the Joint HMT and BEIS Business Productivity Review: Call for Evidence and emphasized that in the UK there was a greater productivity gap among businesses relative to other countries, and that the gap was further widening since the financial crisis. According to Haldane (2017), labor productivity (gross value-added per number of employees), as of 2007, was approximately £100,000 for the top 10% of the businesses, whereas for the bottom 25% it was less than £20,000. By 2014, in the top 10% of the businesses, labor productivity had risen to £120,000, but in the bottom 25%, it remained less than £20,000. The Business Productivity Review argued that the UK had a unique characteristic in which, while the high-productivity businesses were achieving increases in labor productivity, the low-productivity businesses had demonstrated no such increase and that the gap was widening. In light of these facts, the Business Productivity Review presented a hypothesis that low-productivity businesses would be able to catch up in increasing productivity by learning exactly what it was that the high-productivity businesses were doing. HMT/BEIS then widely solicited opinions on this hypothesis and any additional evidence from researchers and strategists which the government might have overlooked in the form of "the call for evidence."

What is the factor that explains the productivity gap among businesses? What is it that the high-productivity businesses are doing? Recent research has been heading in the direction of breaking down the components of firm productivity and numerous studies have been conducted specifically on the quality of management practices. Research is being conducted that assigns scores to the quality of management practices (management scores) through corporate surveys and interviews. Bloom and Van Reenen (2007) have pioneered the research in this field on the U.S./French/German and UK firms, and Miyagawa et al. (2014) are known for their research of Japanese and South Korean firms. It is considered that there is a desirable method of management practices for each business according to the business environment, regulations, etc. For example, the study by Miyagawa et al. (2014) points to the conclusion that the correlation of management practices with firm performance is not as marked in Japanese and South Korean firms as the correlation observed in the U.S. and European firms, and that the crucial factor was each country's unique management environment (e.g. the lifetime employment system), accounting for the fact that improvement of management practices does not necessarily lead to the efficient utilization of labor.

One research group, in which the author participated, collaborated with the UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) and conducted a broad survey on management practices and expectations (MES: Management and Expectations Survey) of the manufacturing and services industries. The corporate survey measured the subjective probability distribution of a company's own future forecast (e.g. revenue). Using the distribution information (dispersion and interquartile range), it built an uncertainty index and empirically clarified its correlation with the quality of management practices and productivity. In short, the survey found that (1) the management scores of firms vary by industry, company and region and that the scores of SMEs were low; (2) firms with higher management scores had higher productivity; and (3) firms with higher management scores tended to more accurately forecast the economic outlook. The survey showed that the more uncertain the future, the stronger the demands were for a system of management decision-making that was capable of responding quickly to the changing business environment and that the quality of management practices heavily impacted productivity and performance.

Our research team invited members of the HMT as discussants at the conference where the research results were presented, and sought feedback on the results of the research at meetings with HMT and BEIS members. To the call for evidence, we submitted documents containing our opinions as well as other research that we were aware of. After Chancellor Hammond's policy announcement, the Director of BEIS suggested that we continue discussions to incorporate our research into the implementation of the policies going forward. In addition to the evidence supporting policy-making, evidence for policy assessment was also required. On this point, we are currently in discussions to empirically measure the effects of the policy using randomized controlled trials (RCT).

The importance of the quality of management practices in explaining the productivity gap among firms had already been proved through research using data from other countries including the U.S. However, what the UK policy-makers were demanding was hard evidence on the firms in the UK. The fact that it was able to obtain the above evidence from its own government statistics seemed to have driven the policy-making process.

3. Three-pronged approach to EBPM: Starting with the economic statistics review

The UK government's announcement that it would review economic statistics as part of its productivity plan set the stage for the above project. In July 2015 then-Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne, gave instructions to conduct a review of economic statistics, and in March 2016, Sir Charles Bean, Professor of the London School of Economics, upon Chancellor Osborne's request, set out his findings in his report (the "Bean Report"). In response to the Bean Report, the government allocated funds in the budget and ONS reinforced its partnership with the researchers and since then has been making joint efforts to improve and develop the statistics on productivity. Moreover, economic statistics have generated scientific evidence, and the importance of using such economic statistics in policy-making has been reinforced. Low-quality statistics cannot beget reliable research results and thus will not be approved by top journals, which, in turn, will not be conducive to the enhancement of the researcher's achievements and will prove useless for policy-making.

In the UK, research evidence is used in policy-making. Therefore, it is commonly understood that creating top-quality statistics that make all this possible is vital. Additionally, researchers in UK universities are encouraged to generate impact, on top of publishing papers in top journals. In fact, the Research Excellence Framework (REF), the assessment framework of the excellence of research in UK universities, emphasises the impact generated by research. The competition for research grants is also often among consortiums comprised of public officials, statistical agencies and researchers.

In this way, EBPM which is becoming firmly established in the UK, is being promoted by the policy-makers, ONS and researchers as part of a three-pronged approach. It is our hope that, in Japan also, further discussions take place on the system for and role of economic statistics, and that EBPM becomes established at an accelerated pace going forward.