The Number of Companies in Japan Falling Steeply

The number of companies in Japan has continued to decline after peaking in the latter half of the 1980s. According to an estimation using census data, the total number of companies in Japan in 2005 was 82 as a percentage index relative to the base of 100 in 1990, and the number in 2015 was 74. I, together with Professor Yoshiaki Murakami of Osaka University of Commerce and Professor Yoshio Higuchi of Keio University, conducted a simulation of how the numbers of companies and employees in Japan will change in the period until 2040. The results show that the number of companies is projected to decline further over the next 10 years, falling to 58 in 2025 relative to the 1990 base of 100 (Note 1). Over the next 10 years, a similar number of companies to the number of companies that disappeared over the 25-year period from 1990 to 2015 will disappear.

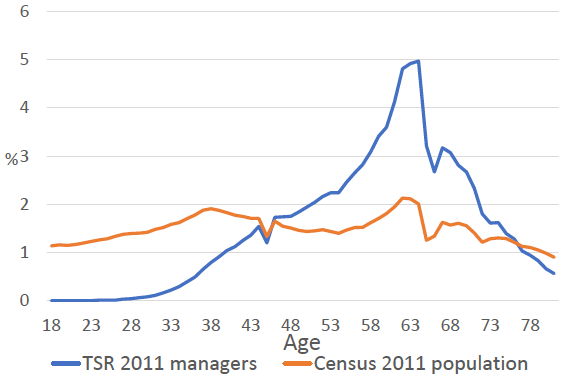

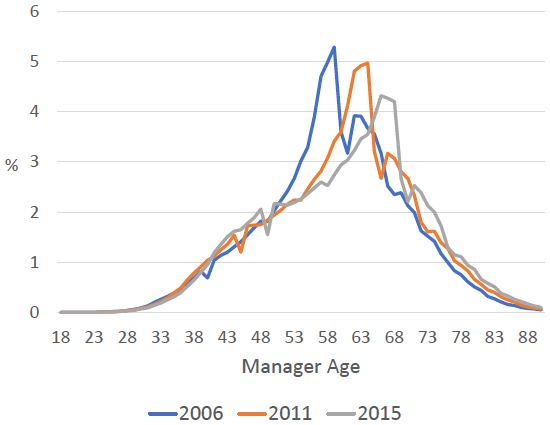

The decline in the number of companies can be explained in large part by demographic changes. Figure 1 shows the age distribution of the population and managers based on the 2011 Economic Census and data compiled by Tokyo Shoko Research (TSR). This figure indicates that the peak age in 2011 was 62-64 years old for both the population and managers, meaning that the babyboomer generation accounts for the largest proportion of the population at large and is in the management positions. In 2015, people in this age group were 66-68 years old, and in 2025, they will become 76-78 years old, ages at which most managers retire. While managers of older generations are retiring, very few people of young generations become managers by starting up new businesses or succeeding existing businesses. Figure 2 shows changes in the age distribution of managers. Their peak age rose from 59 years old in 2006 to 66-67 years old in 2015. The peak age rose by eight years over the nine-year period.

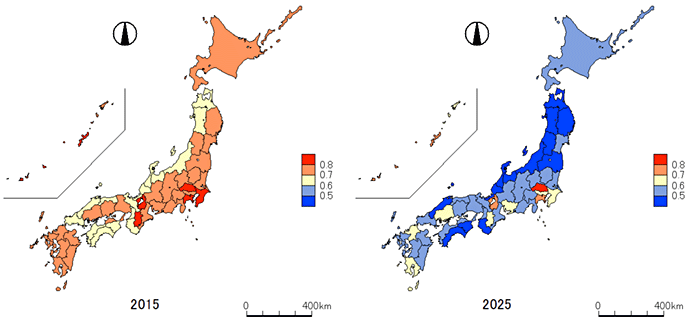

Wide Regional Disparity in the Decline in the Number of Companies

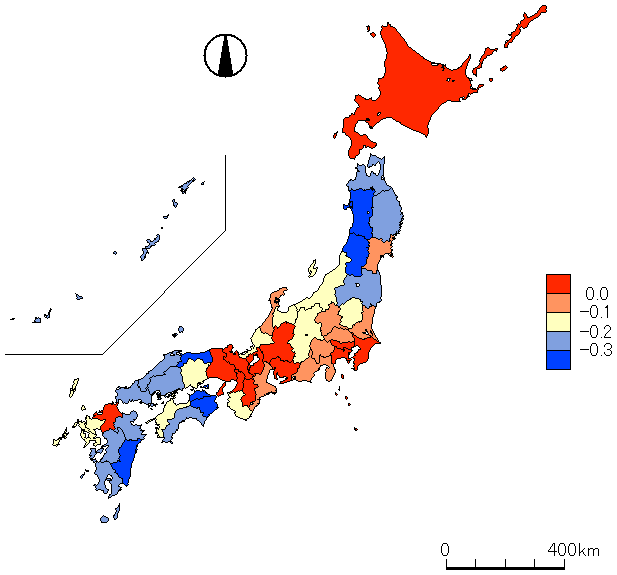

The degree of decline in the number of companies is not even across the country: there is a wide regional disparity. Figure 3 shows changes in the number of companies by prefecture between 2015 (left side of the figure) and 2025 (estimate; right side of the figure). The decline in the number of companies in 2015 compared with 1990 was relatively small in Kanagawa (the number in 2015 was 83 relative to the 1990 base of 100), Shiga (83), Saitama (83), Okinawa (82), and Chiba (82). On the other hand, the decline was conspicuous in Yamaguchi (66), Kyoto (66), Kochi (66), and Akita (67). In these prefectures, the number of companies dropped to around two-thirds of the level in 1990. According to our simulation, the number of companies in 2025 will be less than half the level in 1990 in 14 prefectures, including Toyama (the number in 2025 will be 43 relative to the 1990 base of 100), Yamagata (43), and Kochi (43), where the decline will be the largest. On the other hand, the decline will be relatively small in Saitama (80), Kanagawa (79), Okinawa (77) and Shiga (72). The common characteristics of the prefectures where the decline will be small are a relatively low rate of decline in the working-age population (Note 2) and a relatively high entrepreneur ratio (Note 3). Given that the working-age population constitutes not only a labor supply source and but also a consumer base with needs for products and services, the results of our simulation come as no surprise.

Number of Employees Still Growing but Set to Decline

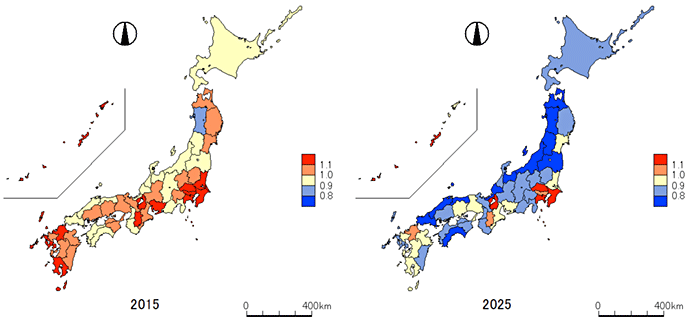

Although the number of companies has continued to decline since 1990, the number of employees (companies' labor demand) in 2015 still remained higher, at 106 as a percentage index relative to the 1990 base of 100. The number of employees is growing despite the decline in the number of companies because relatively large companies have survived while micro businesses and small and medium-size firms have disappeared, with the result that the number of employees per company has risen. The number of employees is currently increasing, but in 2025, the total estimated number of employees in Japan is expected to fall to 93 relative to the 1990 base of 100, according to an estimate based on the simulation of changes in the number of companies (Note 4).

The regional disparity in the decline in the number of employees is yet significant, although it is not so wide as the regional disparity in the number of companies. Figure 4 shows the number of employees by prefecture in 2015 (left side) and in 2025 (estimate; right side). The number of employees in 2015 increased compared with 1990 in 29 prefectures, including Okinawa (the number in 2015 was 134 as a percentage index relative to the 1990 base of 100), Shiga (121) and Chiba (120) (see Figure 4). It is notable that the number of employees increased in all prefectures in Kyushu. On the other hand, the number of employees declined in Akita (87), Yamaguchi (93), Yamagata (93), and Fukushima (93), among other prefectures. According to our simulation, Akita (69) is expected to record the largest decline in the number of employees in 2025, followed by Yamagata (73) and Kochi (73). On the other hand, the number of employees in 2025 will be higher than the level in 1990 in Okinawa (120), Saitama (118), Shiga (112), Chiba (111) and Kanagawa (110), among other prefectures.

Lower Productivity in Regions Where Managers are Older

There may be an argument that even if the number of companies declines, there will be no problem as long as surviving companies create more value. Figure 5 shows relative productivity (sales per employee) by headquarter location, expressed as an index figure with the productivity of companies headquartered in Hokkaido used as the base of 100(Note 5). The productivity index is high in Tokyo (124), Osaka (121), Hyogo (111), and Aichi (110), while it is low in Tottori (55), Yamagata (59) and Tokushima (62). According to Kodama and Li (2018), companies' productivity is at its peak when their top managers' ages are around 50. Their productivity growth rate continues to decline with their ages after they have reached their 30s. In other words, productivity growth is lower in regions where managers are older. Measures to rejuvenate the management ranks will help to improve productivity.

Need to Provide Intensive Support for Business Succession Promptly

The implications of the above analysis are as follows.

First, the number of companies and the number of employees, which reflects companies' labor demand, depend in large part on demographic changes. There is no region where an increase in the number of companies and a decline in the population occur at the same time. These two numbers are mutually related: people live in regions where jobs are available and jobs are created where people live. Demographic policy is the most effective industrial and regional policy.

With that as a premise, what should be done to prevent a decrease in the number of companies or a decline in productivity? The simulation results indicate that both support for business startups, business succession, and curving the decline in business closures are effective in preventing a decrease in the number of companies (for the details, refer to Murakami, Kodama and Higuchi (2017)). Given that people wishing to start a new business have a higher probability of succeeding in doing so in Japan than in other countries, creating an environment that encourages more people to wish to start a new business is important for stimulating entrepreneurship activity. Meanwhile, there are concerns that the number of business closures may have begun to rise rapidly since 2017, when top managers of the baby-boomer generation started to turn 70. With respect to business succession, it is necessary to provide intensive support promptly.

The necessary policy measures are different between regions where productivity remains high despite a decline in employment, such as Osaka Prefecture, and regions where employment is growing although productivity is not very high. It is desirable to keep regions vibrant by providing the optimum combination of support measures, such as measures to support business startups and business succession and to rejuvenate the top management, on a region-by-region basis.

(Note) It should be kept in mind that the simulation results may vary significantly depending on the estimation method, data, assumptions and reference year.

(Reference)

Murakami, Yoshiaki, Naomi Kodama, and Yoshio Higuchi, "Estimates of Future Numbers of Companies and Employees by Region," Financial Review: Population Decline and Local Economies, Vol. 3 of 2017 (Vol. 131) June, 2017, pp.71-96..

Kodama, Naomi and Huiyu Li, "Manager Characteristics and Firm Performance," RIETI Discussion Paper Series 18-E-060, 2018.