As Japan’s population decline accelerates, it has been suggested that a sharp decline in the young female population will lead to the “eventual extinction” of municipalities. However, despite a review of municipal population data over the past 40 years from 1980 to 2020 showing that the female population aged 20-39 has already halved in 879 municipalities, these municipalities have not disappeared as claimed. As 10 years have passed since the discussion of municipalities at risk of extinction was raised in a report published by the Japan Policy Council in 2014, it is necessary to revisit the definition of “extinction” and its side effects on the local economies.

Background

In Japan, where population decline is accelerating, addressing the declining birthrate is an urgent challenge. In 2014, a report published by the Japan Policy Council's Subcommittee on Depopulation Issues pointed out that 896 out of 1799 municipalities were at risk of extinction in the next 30 years to 2040 due to a halving of the female population aged 20–39 [1]. Since then, the national and local governments have taken various measures to revitalize rural areas, such as correcting the over-concentration of population and industry in the Greater Tokyo Area, encouraging migration to rural areas, and supporting child-rearing. On April 24, 2024, 10 years after the report, the Population Strategy Council released an updated report on municipalities at risk of extinction based on the latest data [2].

Considering future prospects and countermeasures against population decline based on data for the past 40 years

Residents of the municipalities that were identified as being at risk of extinction in the latest report of the Population Strategy Council might have felt increasingly anxious about the future when they heard the term "extinction." The first thing to do is not to be overly swayed by future predictions, but to correctly understand the current situation based on past data.

I use the Population Census by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications as long-term time series municipal population data. Specifically, I examine Population Census data for 1980 and 2020 to learn about municipal population trends over the 40 years between 1980 and 2020.

Looking at changes in the female population aged 20-39 by municipality over the 40 years from 1980 to 2020, I find that the female population aged 20-39 had already halved in 879 of the 1,741 municipalities. This number is close to the 896 municipalities that were identified as being at risk of extinction in the 30 years from 2010 to 2040, as pointed out in the 2014 report by the Japan Policy Council.

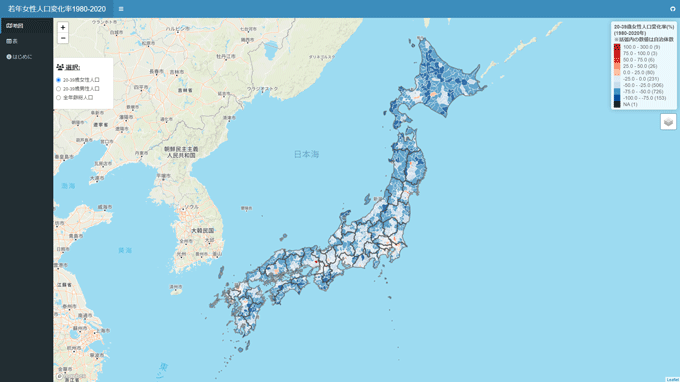

Whereas the 2014 report predicted that 896 municipalities could disappear due to the halving of the female population in question, almost the same number of municipalities have already experienced the halving of this female population, but these municipalities have not disappeared as claimed. It is necessary to reconsider the validity that the “extinction” is realized only on the basis of the decrease of this particular 20-39-year-old female population. The details of the data are visualized on the following web application as shown in Figure 1.

[Click to enlarge]

Web App: Young Female Population Changes from 1980 to 2020 (in Japanese)

https://keisuke-kondo.shinyapps.io/female-population-japan/

First of all, it should be noted that for Figure 1 the 1980 and 2020 municipal population data were not directly comparable due to changes in the municipal boundaries between 1980 and 2020. The difference is attributable due to the large number of municipal mergers in the 2000s. Because of this difficulty, I decided to recount the 1980 municipal population data for 1980 based on the municipal boundaries as of October 1, 2020 and compare the resulting 1980 and 2020 municipal population data. This is a necessary consideration when interpreting the data.

What do the 40 years of recent data tell us about municipalities at risk of extinction? Figure 1 shows blue areas, where the female population aged 20-39 has declined, and red areas, where this population has increased. The overall impression is that most of the areas are colored blue. To understand why the young female population is declining in most areas, it is also necessary to know the rate of change in the female population aged 20-39 in Japan as a whole.

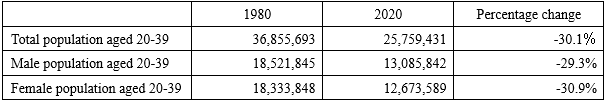

As shown in Table 1, both the male and female populations aged 20-39 declined by about 30% over the 40 years. Looking at the numbers, the impact is even more significant. The total population of Japan continued to grow after the end of World War II before beginning to decline in 2011 [3]. However, the male and female population aged 20-39, who are primarily involved in pregnancy, childbirth, and childrearing, declined by about 11.1 million over the 40 years in question.

Since the total population aged 20-39 has been declining in Japan as a whole, it is unreasonable to attribute responsibility for the decline in the female population aged 20-39 to individual municipalities or to take drastic countermeasures against the population decline. However, it should be noted that the number of women aged 20-39 has increased in 124 municipalities over the past 40 years due to their interregional migration, even though the total number of women aged 20-39 has declined significantly. This increase is substantial in the commuter cities of each metropolitan area. When considering future childcare policies, it may be important to understand what child-rearing households prioritize moving to such “bedroom cities.” Of course, it is also important to investigate households that did not move to such bedroom cities to see if staying outside the cities was in fact preferable, or if they wanted to move downtown but were unable to do so.

Is the argument for “extinction” consistent with the actual situation?

The hyperbolic use of "extinction" may create a sense of crisis about the population decline. However, if the phrase results in harm by implying greater harm than is actually intended, it may be cause for concern. Of course, a report by a private organization does not imply political responsibility. The fact that the risk of extinction has been raised has had the advantage of prompting municipalities to undertake various initiatives. However, it cannot be ruled out that the use of the term itself may accelerate or may have accelerated the outflow of young people from the identified municipalities at risk of extinction or cause or have caused potential residents to avoid those locations because of the expected future decline in property values.

In 2014, for instance, Toshima, one of Tokyo's 23 wards, was identified as being at risk of extinction. While the 2024 report removed Toshima from the list of municipalities facing extinction, it is not clear whether it was really appropriate in 2014 to have classified Toshima as facing extinction. Komine (2017) reviewed the relevant data and pointed out the potential estimation error [4]. The change in the female population aged 20-39 in Toshima over the 40 years came to a 5.8% decrease, far less serious than the 30% decline for the whole of Japan over the same period. (Strictly speaking, data for the 30 years from 1980 to 2010 would be preferable for evaluating the 2014 report). However, it is also true that Toshima dramatically improved the welfare of its residents after being named as a municipality at risk of extinction [4]. It is also conceivable that the negative impact of the 2014 report naming Toshima as a municipality at risk of extinction was limited due to its location as one of Tokyo’s 23 wards.

Additionally, it is questionable whether the percentage decline in the female population aged 20-39 is the most appropriate metric for defining a municipality as being at risk of extinction. For instance, Aomori, the capital of Aomori Prefecture, has been classified as a municipality at risk of extinction. Over the 40 years, the female population aged 20-39 declined significantly, from 51,912 in 1980 to 22,954 in 2020, representing a decrease of 55.8%. Nevertheless, this still leaves 22,954 women in this age group living in the municipality.

Even if a similar rate of decline is assumed over the next 40 years, Aomori will maintain a population of approximately 10,000 women of that age. Moreover, its total municipal population is forecast to be approximately 174,000 in 2050, according to estimates released on December 22, 2023, by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. The question of whether Aomori will become extinct is open to debate when the total size of the municipal population is considered. Regardless of population decline, municipalities should consider implementing community development measures to safeguard local residents.

The most worrisome situation would be the realization of a self-fulfilling prophecy. If the subjective impression given by the term "extinction" unintentionally leads to a further outflow of young people, including women aged 20-39, it may be a matter of concern from a policy perspective. It is therefore important for the government to consider the side effects of the overstated expression.

This paper primarily focuses on visualizing the percentage change in the female population aged 20-39 over the past 40 years. Further research is necessary to determine how to interpret the results. As a basis for determining whether or not municipalities are actually at risk of extinction, this paper publishes the data to clarify future prospects (see the Appendix for details of the data).

Regarding future population distribution forecasts, a research team under Professor Mori Tomoya at Kyoto University has conducted a detailed statistical analysis based on mesh data [5]. This analysis depicts a future in which it will be challenging to sustain some cities due to the decline in population. The presentation of a high-resolution outlook is anticipated to stimulate further public debate on how to prepare for a society with a declining population in the future.

Increasing the role of government in providing necessary child-rearing support and addressing declining birth rates

The publication of the Japan Policy Council report in 2014 played an important role in increasing the momentum for overcoming population decline and regional revitalization. As 10 years have passed since then, it may be opportune to critically examine the 2014 and 2024 reports from various perspectives.

The objective of the 2014 report may have been to persuade municipal governments to take action in response to a perceived crisis surrounding the "extinction." However, if the term “extinction” were overestimated, the report might have inadvertently contributed to a net outflow of young people, including women aged 20-39, from municipalities that were identified as facing the possibility of extinction. There is criticism that regional revitalization measures have led municipalities to compete with one another to attract young and child-rearing populations, while the central government has been required to take measures to improve the birthrate for the whole of Japan. Although such criticism is also recognized in the Population Strategy Council report [2], the repetition of these mistakes is evident.

In addition, it is imperative to reexamine whether municipalities are at risk of extinction based solely on the percentage change in the municipal female population aged 20-39. Of particular concern is the manner in which the lower risk of extinction under the migration restriction would be interpreted. As a potential cause for concern, the analysis may lead to policies that restrict young women’s migration behavior. It is of the utmost importance to recognize that freedom of residence and movement should be guaranteed in principle. It is necessary to reconsider whether these reports represent policy proposals that are overly burdensome only for young women.

When measures to address the declining birthrate and to support child-rearing are considered, it is essential that policy discussions are based on appropriate data analysis. In particular, there are many goals that are difficult to quantify for regional revitalization, leading to many projects based on individuals’ experiences, intuitions, or unfounded ideas. It is therefore necessary to have a policy implementation system that can be verified retroactively. As the number of data science professionals has increased in various fields over the past decade, it is my hope that more people will analyze relevant data to produce a better society for us in the future.

Further policy discussions are required for a future society in which sustainable and affluent lifestyles can be realized regardless of whether people live in urban or rural areas.

May 7, 2024

>> Original text in Japanese