Dec. 11 — the day came quietly while the world's experts in trade law and policies were breathlessly watching the current of events, for some time, to see what would happen on the day. On the day before, Thomas Graham and Ujal Singh Bhatia completed their terms of office, leaving the Appellate Body unable, at last on the day, to maintain the quorum of (three) members to establish a division. The U.S. criticized the Appellate Body for diminishing the WTO members' rights, which are protected under the WTO Agreement, by repeatedly exercising procedural discretion and interpreting treaty texts in excess of the authority given under the Agreement (the so-called "overreach" issue) (Note 1). Now almost three years have passed since the summer of 2017, when the U.S. began to veto the appointment of new members who would replace retiring ones, and the Appellate Body has subsequently ceased to function (Note 2).

Current State and Future of the Appellate Body

Initially, it was expected that the above two members would continue to sit on remaining appeals for the time being according to Rule 15 of the Working Procedures for Appellate Review , and that this approach would be sufficient to process, at a minimum, appeals left pending at that point of time. However, at the end of September 2019, Thomas Graham, a member of the Appellate Body, stated that he would continue to deliberate appeals only if some progress was made in the Body's reform. Further, in November, he also requested that Werner Zdouc, the Director of the Appellate Body Secretariat, resign from the position (Note 3). The gist of Graham's criticism seems to be that the "overreach" issue was caused as a result of the Appellate Body members being controlled under the bureaucratic structure that stuck to the consistent interpretation and operation of the WTO's legal system, and that the removal of the influence of Mr. Zdouc, who has served as the Director for a long period (since 2006) and acts as the leader of the bureaucracy, is indispensable to solving the issue (Note 4).

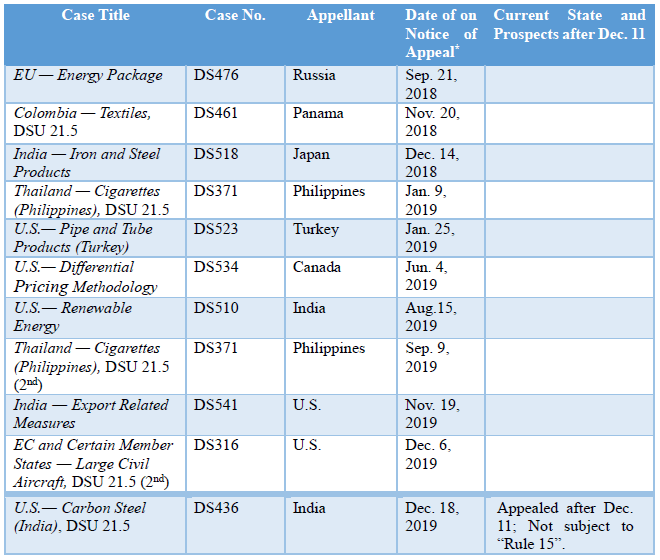

In response to this, the EU, to which Mr. Zdouc originally belongs, expressed its support for the Appellate Body Secretariat. Similarly, at the meeting of the General Council held on December 10th, China stated that it had full confidence in the Appellate Body Secretariat (Note 5). The media soon reported that remaining members agreed with the dismissal of the Director, but as soon as this was reported, a letter by the members was released to the public, stating that they completely disagreed with the media reports, contradicting those false reports (Note 6). With such a chaotic situation, there is no chance that the issue will be solved in the foreseeable future. Accordingly, at this point in time, Mr. Graham is highly unlikely to continue to hear pending appeals, leaving them in a state of limbo. The table below is a summary of the facts.

Since "December 11," the Appellate Body circulated its reports in 3 cases (more precisely 4, as one of these consolidates two appeals) (Note 7), for which oral hearings have already been completed. As shown in the Table, 11 appeals are pending as of writing this report, but they are unlikely to be decided for now. In view of the situation, parties involved in the Morocco — Hot-Rolled Steel (Turkey) (DS513) withdrew their appeal on December 10th and agreed on the adoption of the panel report (Morocco's loss).

What Is Going to Happen in the Future?

Now that the Appellate Body has ceased to function, what can happen from now on? What's most likely to occur is that pending cases appealed on or after Dec. 11 will accumulate in a state of limbo. In other words, the party dissatisfied with the ruling still has the right to file an appeal according to Article 16, paragraph 4 of the Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU); however, once an appeal is filed, it will be left unattended "in the void," as no Appellate Body members will exist to examine the appeal. In practical terms, this means that the dissatisfied party can "block" the adoption of the panel report in the same manner as in the GATT era.

The U.S. has already made the notification of "its decision to appeal" against the compliance panel report on the U.S.― Carbon Steel (India), DSU 21.5 (DS436) on December 18th (see the end of table above) (Note 8). In fact, one cannot be sure whether this officially amounts to "an appeal" or not, because the U.S. has so far not submitted its formal notice of appeal and appellant submission (Note 9). Regardless of the legal status of the notification, since this case is to request a compliance review, the U.S. has no option but to file an appeal. The compliance panel of the case ruled partly against the U.S., therefore, India, the complainant, now has the right to immediately take countermeasures (a "reasonable period of time" is not allowed after the compliance phase). This spearheading action by the U.S. made it easier for other WTO members to choose the option to appeal "into the void," although it is clearly undesirable for the WTO regime.

The second possibility is to agree on acceptance of the panel report as the final ruling, instead of filing an appeal. In this case, the panel report will be adopted as it is by the Dispute Settlement Body (DSB), and the compliance procedures will be followed according to Articles 21 and 22 of the DSU. Such an agreement was actually concluded between Vietnam and Indonesia in the Indonesia—Iron or Steel Products (DS496). It states that if, at the point of time when the case's compliance review report is distributed by the panel, the number of the Appellate Body members falls short of the quorum required to hear an appeal, both parties shall accept the panel's decision as final (Note 10). Korea and the U.S. also agreed on non-appeal of panel report in U.S. —OCTG (Korea) (DS488), if either of the parties have a recourse to compliance review under Articles 21of the DSU (Note 11).

However, if the complained party wins (the panel finds no violation), an appeal "into the void" by the complainant has no effect on the complained party. On the other hand, if the complained party loses (the panel finds a violation), it can appeal the panel's ruling "into the void" to avoid the implementation of the ruling, including the elimination of the violation. Therefore, defendants are not motivated to agree ex-ante not to appeal (Note 12). It is indeed more unlikely to reach an agreement after the panel issues its interim report and the outcome becomes predictable. Both of the Vietnam-Indonesia and Korea-U.S. pacts are intended to prevent an appeal of the decision made by the compliance review panel, rather than any decision regarding the original proceedings. In particular, in the Vietnam-Indonesia case, it was agreed just before the withdrawal of the measure in question, at the stage when it was clearly known that the case was highly unlikely to be brought to the compliance review panel (Note 13).

Further, if the Appellate Body is not functioning in the first place, members will be less motivated to use the WTO dispute settlement procedures. This is clearly shown by the recent U.S.-China relationship that if a country considers that the WTO procedures are not capable of achieving its trade interests, it will resort to unilateral tariff increases and import restrictions. In that case, the third possibility is that every trade dispute between nations could devolve into a "mini trade war," as defined by Rep. Stephanie Murphy (D–FL), a member of the U.S. House of Representatives' Ways and Means Subcommittee on Trade, albeit of a smaller size than that between the U.S. and China (Note 14). If WTO members can appeal "into the void," they will not hesitate to implement protectionist measures in the future. In retaliation, more WTO members will resort to unilateral measures as the Appellate Body is paralyzed. Such measures will be particularly effective for large economies such as the U.S., China and the EU (Note 15).

We cannot expect that events will unfold as predicted in any one of these scenarios; they are equally likely to occur depending on the circumstances of respective disputes. However, while the two other options will significantly undermine the rule of law in the WTO regime, they are more likely to be adopted than the no-appeal agreement.

EU's Attempt to Maintain the "Rule of Law"

EU's Attempt to Maintain the "Rule of Law" A group of 19 WTO members, led by the EU, and including major trading partners like Australia, Brazil, Canada and China, had been in search of a possible approach that could be used in lieu of appeals in anticipation of the paralysis of the Appellate Body. They finally reached a plurilateral agreement in April 2020 concerning an interim arrangement alternative to appeals, pursuant to Article 25 of the DSU ("Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement" (MPIA)) (Note 16). The arbitration outlined in Article 25 of the DSU is a highly versatile procedure with no specific uses or purposes. It has been used only once in the calculation of monetary compensation in the U.S.—Section 110 (5) Copyright Act (DS160) (Note 17).

The MPIA is intended to replicate in the DSU Article 25 arbitration, as closely as possible, the appeal procedures provided for in relevant provisions in the DSU and other documents, in particular, Article 17 of the DSU and the Working Procedure for Appellate Review, including the provision of support by the Appellate Body Secretariat. Arbitrators will be selected from the pool of arbitrators, including available former members of the Appellate Body.

There is no possibility of the U.S. showing interest in this procedure, as Jennifer Hillman, a former member of the Appellate Body who has an extremely critical view on the current mechanism of the Appellate Body, criticized the procedure as "the Bad" approach that would allow shortcomings of the Appellate Body procedures to remain as they are (Note 18). However, in December 2019, the EU announced its plan to amend Regulation (EU) No 654/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council (Note 19) and immediately take countermeasures against a respondent who does not agree to the interim procedure above and appeals "into the void" in a WTO dispute brought by the Union (Note 20). At the EU Council meeting in April 2020, all the EU member countries supported and even reinforced the Commission's idea, suggesting that the Commission should assess a potential need for extending the scope to services and intellectual property rights within three years from adoption of the regulation (Note 21). Clearly, the EU is going to take unilateral measures prohibited under the WTO agreements, especially in terms of Article 23 of the DSU. However, it is indeed paradoxical and ironic that the rule of law can only be maintained through such force.

However, some resource-related issues must be solved before implementing the MPIA. The MPIA specifies qualifications for an arbitrator as "persons of recognised authority, with demonstrated expertise in law, international trade and the subject matter of the covered agreements generally," which does not limit prospective arbitrators to former Appellate Body members. Relaxing the qualifications for arbitrators in the MPIA is a wise choice because availability of the former Appellate Body members is limited. Some of the members have already passed away (Note 22) or are in their eighties. Others, including Thomas Graham and Jennifer Hillman from the U.S., would not accept the appointment to an arbitrator position due to personal or political reasons. However, if the majority of arbitrators consists of non ex-Appellate Body members, it could be difficult to ensure continuity and consistency of legal interpretation with the Appellate Body's precedents.

As for the support by the Appellate Body Secretariat, given that Appellate Body itself has ceased to function and its operating budget has decreased significantly due to strong demands by the U.S., staff in the secretariat , who are in charge of providing practical support, have been largely reassigned across the WTO Secretariat (Note 23). Additionally, it is not clear from the text of the MPIA, who will bear the costs, including the personnel costs of the arbitrators, and what financial resources should be used. In fact, the U.S. raise an objection to use any WTO budget for MPIA in a letter to Mr. Roberto Azevêdo, WTO Director-General of the WTO (Note 24).

Deadlocked Walker Process and Outlook of the Appellate Body Reform

On the other hand, as part of the Appellate Body reform, a series of informal meetings (the so-called Walker Process) were held starting in January 2019, with David Walker, Ambassador of New Zealand, as the facilitator. As a result of this process, a draft decision (the Walker Principles) was issued by the General Council in October (Note 25). Ambassador Walker explained that the decision reflected the points of convergence drawn from discussions and proposals made in the Process (Note 26). Table 2 below is an outline of the results.

| Item | Outline |

|---|---|

| 90-day deadline | In principle, the deadline must be adhered to, but may be extended if so agreed by parties to a dispute. |

| Rule 15 | The selection process for replacement of outgoing members shall be automatically launched 180 days before the expiry of their term; no member should be assigned to a new appeal within 60 days before the expiry of their term; members may continue working on their allocated cases even after their term has expired. |

| Interpretation of municipal law | To be considered as an issue of fact not reviewable on appeal; not subject to a "de novo" review by the Appellate Body; parties to a dispute should refrain from making an attempt to have factual findings overturned under Article 11 of the DSU. |

| Advisory opinions | Consistent with Article 3.4 of the DSU, the Appellate Body shall address raised issues only to the extent necessary to resolve the dispute in support of DSB's advice. |

| Precedent | Precedent is not created through the Appellate Body's rulings, but consistency and predictability in the interpretation is of significant value; panels and the Appellate Body should take previous reports into account to the extent they find them relevant in the dispute they have before them. |

| Overreach | As provided in Articles 3.2 and 19.2 of the DSU, panels and the Appellate Body cannot add to or diminish the rights and obligations provided in the covered agreements; panels and the Appellate Body shall interpret provisions of the Anti-dumping Agreement in accordance with Article 17.6 (ii) thereof. |

| Dialogue between DSB and Appellate Body | A mechanism will be established for dialogue between the two bodies; to safeguard the independence of the Appellate Body, ground rules will be provided to ensure that there should be no discussion of ongoing disputes or any member of the Appellate Body. |

In this process, the U.S. made no proposals, and continued to ask why the Appellate Body felt free to depart from the clear text of the DSU (the so-called "why" question), insisting that it would not agree to the appointment of new members to fill vacancies until this fundamental issue was addressed seriously by the WTO Members (Note 27). This attitude has been strongly criticized by other WTO Members such as the EU and China, who are in favor of the preservation of the judicial appeal procedures (Note 28). Simon Lester of the Cato Institute said that, if the U.S. was not going to submit any solution proposal, it could not be said to be acting in good faith; however, its vague attitude was attributable to a lack of consensus within the office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) about the future of the WTO's dispute settlement procedures (Note 29).

Concerning the attitude of the U.S. government in conjunction with the arrival of Dec.11, some voices emerged from business communities and conservative powers in the U.S., the core constituency of the Trump administration, urging an active involvement of the country in the reform of the Appellate Body, focusing on the implementation of the Walker Principles. More than 30 conservative and economic groups, including Americans for Prosperity (a conservative non-profit organization that has a close relationship with the Koch family, a conservative donor), sent a letter to the President. It was intended to show their support for the multilateral trading system, which provides certainty to the U.S. business community, and to urge his administration to actively engage in the Appellate Body reform (Note 30). The U.S. Chamber of Commerce also called for the restoration of the WTO's dispute settlement procedures, emphasizing the benefits it would bring to U.S. companies (Note 31). In the Congress, the House Ways and Means Committee adopted a resolution announcing its support for the WTO. While the administration's stance towards the Appellate Body issue has bipartisan support, some (mainly Republican) members of the Committee criticize the administration for its unwillingness to engage in the Appellate Body reform (Note 32).

It was widely agreed that the next milestone would be the 12th Ministerial Conference (MC12), which was originally scheduled to be held in Nur Sultan, Kazakhstan in June 2020, but which was postponed due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has also made the WTO unable to convene regular meetings in Geneva since March 2020. Members continue to be divided over whether they should take up more decision-making work over the internet (Note 33). Members, therefore, have been unable to reschedule MC 12 simply because they cannot meet at the General Council in Geneva, though they are now exploring the possibility of scheduling a new date for the Ministerial in the July meeting of the Council (Note 34). Even worse, on May 14, Director General Azevêdo suddenly declared his resignation as of Sept. 1, 2020, which is a year earlier than the expiration of his term. The members will engage in a few-month-long political process to replace DG Azevêdo. Under the circumstances, a loss of momentum in the Appellate Body reform seems inevitable.

Ultimately, this issue will depend on the Trump administration's WTO strategy. There seem to be no immediate factors that will cause the current administration to change its stance. On the contrary, the administration now has more incentive to ensure recourse to unilateral trade sanctions against China, skipping the WTO dispute settlement procedure, as tensions of the bilateral relationship increase due to U.S. accusations against China related to the Covid-19 pandemic and its application of the National Security Law to Hong Kong, as well as fierce bilateral rivalry for dominance in 5G networks. The EU, which opposes the administration's approach, is hoping for a change in the U.S. as a result of a political power shift after the presidential election in the fall of 2020. The circumstances, therefore, will remain the same at least until the election (Note 35).

On the other hand, intellectuals in Washington point out the possibility of the U.S. losing negotiating leverage and the Appellate Body reform losing momentum as a result of these alternative measures, including MPIA and the no-appeal pact, with them becoming the "new normal (Note 36)." Jennifer Hillman, a former Appellate Body member, suggested that the concern was particularly acute for an MPIA-type interim appeal process (Note 37).

Japan Benefits from Appellate Body's Judicial Nature

So then, how should Japan respond to these circumstances? Basically, I always consider that Japan should work more actively with the EU and other groups that seek to maintain the Appellate Body's judicial nature and independence, while assuming the U.S.'s involvement as a premise. The reason for this is that Japan has benefited significantly from the WTO's dispute settlement procedures, and therefore the maintenance of the rule-oriented multilateral trade system contributes to our national interest. It is regrettable to say that Japan has lost some of its influence as a trading nation compared to the days in 1980s and 90s when it enjoyed, as the world's second largest economy, being praised for its prosperity as in the book title "Japan as Number One," and leading trade negotiations with other members that constituted the "Quad," i.e. the U.S., the then EC/EEC, and Canada. Under such circumstances of diminishing power, it is even more important for Japan to rely on the rule of law, instead of the rule of power.

The following figures illustrate the above assertion.

| Capacity | Cases | Panel (Appellate Body) Report | Cases won* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cases as complainant | 27 | 18 (13) | 18 (13) |

Cases brought to compliance review process |

1 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Cases as respondent | 16 | 5 (4)** | 1 (0) |

Cases brought to compliance review process |

1 | 1 (0) | 0 (0) |

| * Cases won: Cases in which any one of Japan's claims was accepted. ** = One panel report for a mutually agreed solution is NOT included (DS323). |

|||

As shown above, in the past, the number of appeals filed against Japan was significantly lower than those it filed. If limited to cases that were actually brought to a panel for its ruling, the number filed against it is only one-third of the number it filed. Moreover, Japan succeeded in having at least one of its arguments or claims accepted in most of the cases it lodged. It is indeed a result of its exemplary attitude towards avoiding protectionist trade policies, but these figures show how Japan has benefited from the system.

More importantly, the country has benefited significantly from the "overreach" of the Appellate Body. In the early 2000s, there were a number of WTO disputes between Japan and the U.S. Then-President Bush won his first presidential election by, just like President Trump's first term, securing victory in fierce battles in the mid-western "rust belt" states, which were suffering from the reduction in the iron and steel industry, and the protection of the industry was one of his election promises. This caused the U.S. to implement numerous protectionist trade remedies and laws around 2000. In response to this, disputes were successively brought to the WTO by Japan, the EU, and other U.S. trading partners, and resulted in wins by the complainants. All these disputes provide a basis for the current U.S. criticism against "overreach." That is, Japan succeeded in restricting the U.S. protectionism, thanks to the Appellate Body's interpretation, which applied an active problem-solving approach and virtually constructed a body of case law under the principle of jurisprudence constanté as well. The success resulted in the repeal of legislations and measures in almost all cases.

| Case | DS No. | Circulation Date | Outcome | Rulings Associated with the "Overreach" Criticism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S.—Zeroing (Japan) | 322 | Jan 9, 2007 | Revision of rules | The zeroing method should not be applied in calculating dumping margins in any of the original investigations, periodic reviews, or sunset reviews |

| U.S.—Steel Safeguard | 249 | Nov. 10, 2003 | Immediate removal of the measures |

|

| U.S.—Offset Act (Byrd Amendment) | 217 | Jan. 16, 2003 | Repeal of the legislation | Anti-dumping and countervailing tax duty revenues shall not be disbursed to domestic industries that requested the initiation of investigation. |

| U.S.—Hot-Rolled Steel | 184 | Jul. 24, 2001 | Partial amendments to the measures | In a causation analysis between increased imports and material injury, injurious effects of the increased imports must be separated and distinguished from the injurious effects of the other factors (non-attribution analysis). |

| U.S.— 1916 Act | 162 | Aug. 28, 2000 | Repeal of the legislation | It is impermissible to respond to dumping by imposing punitive damages or criminal penalties. |

Without the Appellate Body's rulings, these results would never have been achieved regardless of the number of talks held, as clearly shown by the negotiations on rules in the deadlocked Doha Round talks. This is evident if we look at the U.S.—Corrosion-Resistant Steel Sunset Review (DS244), the only case we lost among this period's series of disputes pertaining to the U.S. protectionism over steel products. Japan has not yet succeeded in having the U.S. amend its domestic regulations relating to the sunset review on anti-dumping duties, which was the goal Japan tried to achieve by lodging the dispute. We also suffered a setback due to the Appellate Body's reluctance in the Korea—Radionuclides (DS495) in April 2019. It is still fresh in our memories that, in this case, Japan received an adverse ruling as the Appellate Body respected South Korea's discretion as to its food safety regulations, against the backdrop of the criticism by the U.S. against the Body's "overreach (Note 38)."

In addition, if we had tried to settle trade disputes without relying on the WTO dispute settlement procedures, we frequently would have been required to wage "mini trade wars" against the U.S.—which, as mentioned earlier, are fought to settle individual trade disputes. One can easily imagine that, considering Japan's heavy respect for the bilateral alliance with the U.S., if Japan had tried to adopt such an aggressive strategy, it would have probably found it next to impossible to take the option. We could use the WTO dispute settlement procedures against the U.S. without hesitation because trade disputes were depoliticized through the settlement process and turned into "business as usual" performed by experts, as appropriately provided for in Article 3.10 of the DSU: "… Requests for use of the dispute settlement procedures should not be intended or considered as contentious acts."

Japan to Share Its Vision and Make Contributions

What responses has Japan provided so far? While the country does not explicitly support the U.S.'s criticism against "overreach," it also does not strongly advocate either the EU's proposal designed to strengthen the Appellate Body's independence and autonomy or the alternative MPIA plan. Japan apparently hoped to act as a good-faith mediator between the U.S. and the EU, the two parties having conflicting judicial views.

This was most apparent in the Japan-Australia-Chile joint proposal in April 2019 (Note 39). While the proposal shows understanding of the issues raised by the U.S., it is basically intended merely to confirm the current Agreement rather than to make revisions thereto. Japan, in the proposal, presented its sincere response to the U.S.'s statement of concern on the issue, and at the same time upheld the EU's position, which basically preserves the current judicial dispute settlement system. The Walker Principles take an approach similar to this joint proposal, indicating the intellectual contribution provided by Japan's proposal.

In addition to the joint proposal, Japan has made contributions to the Walker Process. First, when the Process was launched, Junichi Ihara, the Chair of the WTO General Council (Permanent Representative of Japan to the International Organizations in Geneva) demonstrated his initiative by launching this process. Further, at the G20 Osaka summit in 2019, Japan expressed its commitment to WTO reform in the Leader's Declaration and the G20 Ministerial Statement on Trade and Digital Economy. In particular, the Statement clearly states the following: "We agree that action is necessary regarding the functioning of the dispute settlement system consistent with the rules as negotiated by the WTO Members (Note 40)." To obtain consensus for this sentence from other nations, and particularly from the U.S., Japan exerted a great deal of effort, as the presiding country (Note 41).

Japan played an important role as an intermediary between the U.S. and the EU to prevent a crisis before Dec. 11. However, now the date has come and gone, and the crisis has become a reality. Accordingly, the issue has already entered a new phase, and some changes have occurred in the role to be played by Japan. Given that these circumstances will continue for the foreseeable future, it is necessary for Japan to develop a vision that lays out what is a desirable "new normal" and what functions the Appellate Body should have beyond the "new normal." As described in the preceding paragraphs, Japan has benefited from the WTO's dispute settlement procedures—more precisely, from the highly judicialized nature of the Appellate Body's rulings. In view of this, the vision clearly should have its basis in the preservation and promotion of the judicial nature of the Appellate Body, adopting a pro-EU stance.

However, Japan still lacks its own vision. Regarding a short-term solution, Japan has not joined the aforementioned MPIA, though Japan reportedly expressed an interest in this alternative plan (Note 42). To safeguard the rule of law in the multilateral trading system, we need to consider taking concrete steps towards supporting the EU's initiative.

Japan has also failed to clarify its stance toward a longer-term, more macroscopic vision. According to the media, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe stated, during his official travel abroad in the 2019 "Golden Week" holidays, that reform would be critical to ensuring the functioning of the dispute settlement process, in response to the reversal of the ruling from Japan's win to a loss in the Korea—Radionuclides (DS495) (Note 43). The media also reported that he shared the same awareness of the issue involved in the ruling and the need for DSU reform, as the leaders of the U.S., the EU, and Canada (Note 44), but I couldn't help but feel uncomfortable about the comment. As mentioned above, the U.S. criticizes the Appellate Body's ultra vires act based on its "overreach" argument. On the other hand, the EU, along with China and India, are interested in finding a method of preserving the Body's judicial nature and autonomy. Canada also shares the same opinion with the EU, including regarding the MPIA. In this sense, these nations are working together with distinctly different goals, and it is therefore completely unknown in what respect the PM Abe found agreement with the other leaders, who seem to have disparate goals.

In his meeting with Foreign Minister Kono in May 2019, Robert Lighthizer, the U.S. Trade Representative, reportedly said that he did not want to see Japan sacrificed by the Appellate Body issue in this way. However, Ambassador Lighthizer also said as a preamble that the U.S. was fully aware of the Body's issue through its experiences in a number of cases (Note 45). As mentioned above, this "Appellate Body's issue"—i.e. its "overreach"— has provided Japan with favorable outcomes in the past, while the Body's reluctance caused by the U.S. criticism resulted in Japan being "sacrificed" (that is, the reverse of the ruling from Japan's win to a loss in the Korea—radionuclide). Given that, if the government is bolstered by Ambassador Lighthizer's words and considers that it has gained support from the U.S., any vision Japan may have for an ideal Appellate Body is completely incomprehensible.

More seriously, Japan does not support the repeatedly proposed launch of the selection process for Appellate Body members. This proposal (Note 46) was jointly issued by a group of Members ranging from developed countries and key emerging economies such as the EU, Australia, Canada, Mexico, Brazil, and India, to the world's poorest countries including Burundi, Central Africa, and Malawi, and is now supported by as many as about 120 countries (Note 47). This demonstrates that almost all the major economies support this proposal, while only Japan and the U.S. among OECD members, and these two countries and Saudi Arabia among G20 economies, have never supported the initiative (Note 48). In addition, Japan endorsed the U.S.'s statement criticizing, as "overreach," the Appellate Body's long-held interpretation of Article 6.2 of the DSU, which allows for the terms of reference to be given to the panel. The statement was issued when the panel/Appellate Body report was adopted in the Korea — Pneumatic Valves (DS504) (Note 49). Does Japan intend to support the U.S.'s argument and a series of actions that are based on its "overreach" theory? If so, is it prepared to abandon the benefits obtained from the accumulation of precedents it won through the Appellate Body's interpretation? How would this contribute to our national interest? And, finally, what is most shocking to the author is that Japan even qualified the Appellate Body as "discredited" at another DSB meeting, criticizing the EU's idea of duplicating the current appeal procedure and practices in MPIA (Note 50). But, as far as I know, no other country other than the U.S. clearly agrees that the system has been discredited. Again, is Japan joining the U.S.? If so, what would justify the decision in terms of our national interest? Unfortunately, these actions seem to be mere obsequiousness to the U.S., arousing a sense of worry about Japan's lack of vision for a workable goal for the Appellate Body issues.

Again, I personally believe that our national interest lies in the basic preservation of the current Appellate Body and that what is appropriate for Japan is to strengthen ties with the EU. However, if the government views that there are other solutions, and the view is based on a well-considered policy decision, it should not be immediately rejected. The true issue is the non-existence of consistent national policy, vision, and underlying policy decisions. Finally, it is fitting to conclude this paper by proposing that more serious discussions should be held regarding the following topics and others, focusing on the national interest of Japan:

- As a short-term issue, what risks do we face because of the paralysis of the Appellate Body? In particular, given the large number of cases Japan has filed as a complainant, what risks do current appeals "into the void" represent?

- Based on the above, what are the pros and cons of participating in the EU's MPIA plan to use the arbitration procedures, in lieu of appeals, based on Article 25 of the DSU?

- As a medium-term issue, how should we evaluate the Appellate Body's "overreach"? What aspects of the U.S.'s criticisms do we agree or disagree with?

- If we agree with the U.S., how could we ensure consistency with the fact that Japan has benefited from the "overreach," and what advantages and disadvantages does this present? In some cases, we may lose some precedents that benefited Japan, but which are strongly opposed by the U.S. (e.g. prohibition of zeroing). Is this an acceptable cost?

- What is the ideal state of the Appellate Body for Japan? Specifically, should we support the EU in order to preserve a judicial Appellate Body? Or should we advocate the stance of the U.S., which champions an Appellate Body that focuses on the arbitration of individual disputes? Needless to say, there may be other options in addition to the two above, but what are the elements essential to Japan's interests?

The original text in Japanese was posted on December 27, 2019.