Accurately predicting the labour market impact of trade shocks is a complicated endeavour. Using job match records merged with firm-level customs records and changes in potential tariffs following China’s WTO accession, this column shows how differential firm-level exposure to China’s accession led to concentrated earnings and employment losses in the US. However, labour market competition among workers also diffused and reallocated earnings and unemployment losses among many seemingly untargeted kinds of workers. These findings are relevant for understanding the earnings and unemployment implications of the emerging trade war.

The US has recently announced and imposed a host of new tariffs on China, Canada, and the EU, which prompted these countries to impose retaliatory tariffs, with $1.2 trillion in US imports and exports potentially affected (York and Durante 2025). News reports abound with predictions about which kinds of firms and workers will gain and lose from a new trade war.

Yet accurately predicting the labour market incidence of such multifaceted trade shocks is a complex endeavour. It requires identifying (1) which firms' product demand and costs are most affected, (2) how sensitive their employment demand is to these changes, (3) what kinds of workers such firms tend to hire and retain, and (4) which other workers and firms compete elsewhere with and for the directly affected workers.

In a recent paper (Carballo and Mansfield 2025), we assess the role played by these four factors in the early impact of China’s 2001 WTO accession on US workers’ employment and earnings.

Well-established research (e.g. Autor et al. 2013, Dix-Carneiro and Kovak 2017a, 2017b, Kovak and Morrow 2022a, 2022b, Pierce et al. 2024) shows that trade liberalisation had profound effects on workers. But by relating industry or county exposure to increased import competition directly to worker outcomes, this research mostly sidesteps how differential firm exposure and competition among workers mediate the impact of trade shocks.

We use customs records on each firm’s product mix among imports and exports, and domestic sales along with detailed product-level tariff changes to measure firms’ exposure to each of four channels through which China’s WTO entry might have affected their labour demand: import competition in domestic markets, export access in China, export competition from Chinese products in other foreign markets, and improved access to Chinese imports for existing importers. We then assess how employment growth differed for more versus less exposed firms within industry, size, average pay, and trade activity categories, with employment sensitivity to exposure allowed to vary across these categories.

We then use predictions of firms’ shock-induced employment changes as inputs in a labour market model estimated via millions of job transitions and retentions from administrative records. The model simulates how competition among workers from different industries, regions, and pay levels translates the initial job creation and destruction to a distribution of medium-run earnings and unemployment impacts. Our analysis produces several insights that we believe are relevant to the current context.

Firms’ trade exposure and employment sensitivity

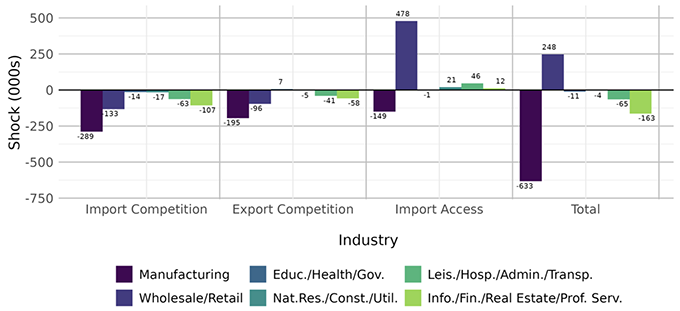

The export competition and import access channels can be major sources of job destruction and creation. Our estimates suggest that China’s WTO entry produced a net reduction of around 628,000 jobs over the first five years. While greater import competition in the US market was the primary driver, there was considerable but somewhat offsetting job destruction from greater export competition (around 388,000 net jobs lost) and job creation from expanded import access (around 407,000 net jobs) (Note 1).

[Click to enlarge]

Non-manufacturing establishments can account for large shares of gross employment changes from trade shocks. Interestingly, we find that 51.8% of the job destruction via import and export competition and all the job creation via expanded import access occurred among non-manufacturing establishments.

Multinational firms engaged in intrafirm international trade are likely to account for an disproportionately large share of each channel's shock-induced employment changes. In our analysis, multinational firms contributed at least 70% of the aggregate job change for all three primary channels despite representing only 26.6% of US jobs. This reflects the fact that multinationals account for 83.0% of US imports and 81.6% of exports, making them disproportionately exposed to this and most trade shocks.

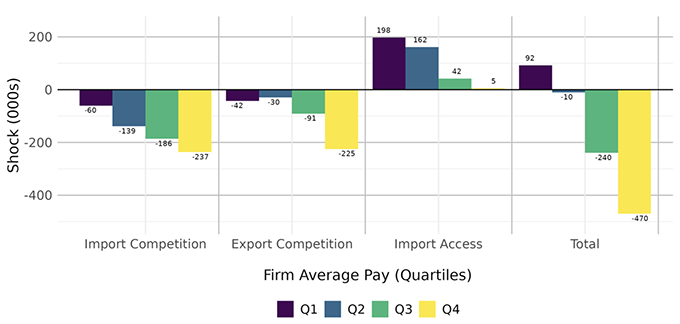

[Click to enlarge]

Shock-induced employment losses were concentrated in high-paying firms, while employment gains were concentrated in low-paying firms. Firms in the top two average pay quartiles accounted for 67% and 81% of jobs destroyed by the import and export competition channels despite employing 50% of US workers. By contrast, the two lowest paying quartiles account for 88% of jobs created by expanded import access. Thus, the immediate impact of the current tariff retaliation on exporters may disproportionately impact middle- and high-paid workers, while disruptions to importing are more likely to cause initial distress to low-paid workers.

[Click to enlarge]

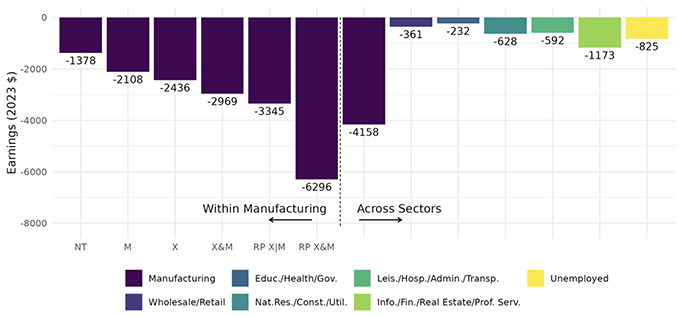

Labour market competition and worker incidence

Trade shocks can produce concentrated earnings losses when several channels align to target particular worker types. Workers initially at multinational manufacturing firms suffered the largest loss from China’s WTO accession, around $6,000 per worker over the subsequent five years. These losses partly reflect the increased competition such multinationals faced domestically but also internationally, since they rely more heavily on exports for revenue. But they also reflect that manufacturing multinationals were best equipped to exploit new opportunities to outsource from China inputs that their US workers had previously produced.

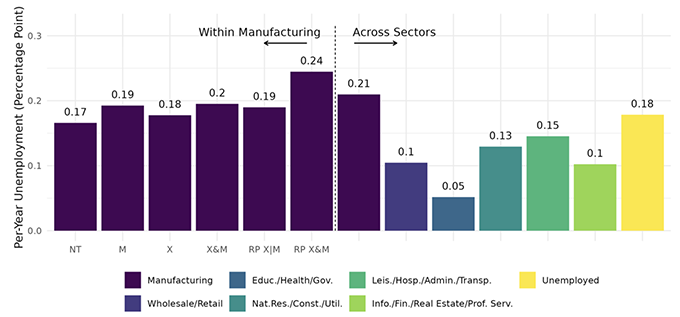

[Click to enlarge]

[Click to enlarge]

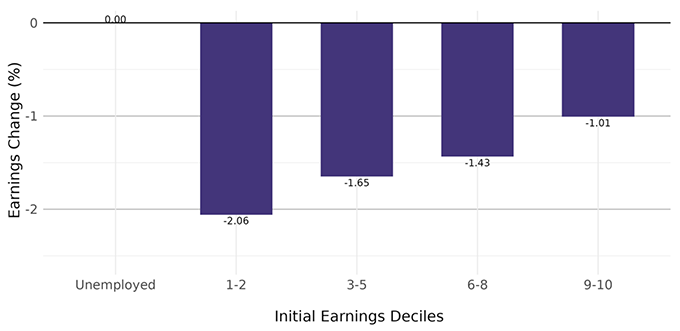

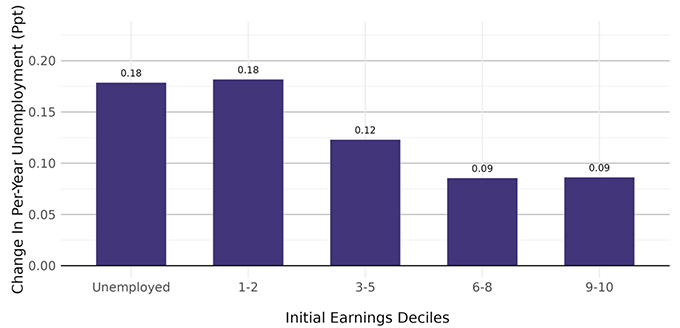

Over time, job ladders within and across industries cause large shares of earnings gains or losses to trickle down to lower-paid and initially unemployed workers, even for trade shocks targeting high-paying firms or industries. Despite their concentrated losses, we find that 2001 manufacturing workers only experienced 48.8% of aggregate earnings losses and 20.8% of additional years of unemployment caused by China’s WTO entry between 2002 and 2006. Most notably, reduced opportunities to move to manufacturing and increased competition for jobs from displaced manufacturing workers cause workers in the low-paid leisure/administration/transportation industries to bear 10.7% of shock-induced earnings losses and 22.2% of increased unemployment, even though their firms generally were not directly targeted by any channel.

Similarly, we find that initially unemployed workers account for 13.4% of additional years of unemployment despite representing 9.05% of the 2001 labour force and having no job for a trade shock to target. As stiffer competition for fewer remaining jobs leads many workers to settle for less appealing positions, the workers squeezed out of employment tend to be those already struggling to find jobs who might have succeeded in a better labour market.

[Click to enlarge]

[Click to enlarge]

Even neutral trade shocks that generate job gains and losses of similar size can cause short-run average losses in worker wellbeing. One surprising finding is that even wholesale/retail workers whose sector experienced strong net job creation nonetheless suffered earnings losses relative to those most insulated from the shock, high-paid workers in education, health, and government. This is partly because many of these workers would have sought jobs in industries that reduced employment, but also because the shock-induced job creation in wholesale/retail due to greater import access generated relatively small worker earnings gains (Note 2). One explanation is that while job destruction eliminates previously valuable firm-specific experience and forces costly job search for workers, filling new positions also requires search, recruiting, and training costs, limiting gains in workers’ well-being in the short run.

A second explanation is that most job creation in wholesale/retail was at low-paying firms with high job turnover rates (Note 3). Job retention rates among positions expected to be created or eliminated by trade shocks are an underappreciated indicator of how concentrated shock-induced gains and losses in worker well-being will be. This is partly because workers who obtain jobs in high turnover industries may face greater layoff risk, limiting their long-term earnings value, but also because high turnover may reflect worker search effort stemming from a low-quality work environment.

Conclusion

A couple of caveats are necessary when applying our results to the current context. First, purchasing power gains from price reductions likely offset some labour market-related losses due to China’s WTO entry, and may now exacerbate labour market losses from greater export competition and reduced import access. Second, the perceived impermanence of current tariff changes could strongly affect their impact on workers. In 2001, strong international commitment to the WTO meant there was broad faith that China’s entry would remove the possibility of new trade barriers restricting China’s access to international markets in the following years. Because the current tariffs may be revoked if other conditions are met (e.g. drug or immigration enforcement), considerable uncertainty exists about their duration. As such, firms may be reluctant to reshore jobs in America or alter supply chains until the trade landscape has settled (Carballo et al. 2018, 2022). Thus, increases in domestic labour demand from reduced import competition may be slow to materialise, while losses from decreased opportunities to export and import may be almost immediate.

This article first appeared on VoxEU on March 31, 2025. Reproduced with permission.