This month's featured article

Measuring the Cost of Fiscal Reconstruction

KOBAYASHI KeiichiroSenior Fellow

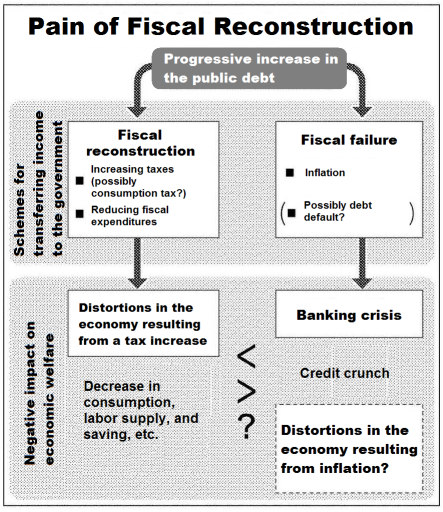

As the discussion on the need to increase the consumption tax rate and raise the pension eligibility age deepens, pains accompanying fiscal reconstruction are looming as a real possibility in Japan. Meanwhile, as we can see from the ongoing crisis in Europe with Greece as its epicenter, it is hard to predict what will happen to the economy in the event of a failure to restore fiscal order. When we discuss fiscal reconstruction in Japan, we must assume the economic welfare cost involved, or the negative impact on the level of satisfaction for society as a whole. That is, to compare and determine the lesser of two painful scenarios: the decrease in the standard of living that would result from fiscal consolidation measures such as tax hikes and cuts in public expenditures and the disruption of people's lives in the event of fiscal failure.

♦ ♦ ♦

Regarding the economic welfare cost resulting from fiscal reconstruction in the first scenario, there has been significant progress in research efforts. An increase in taxes and a decrease in public spending would result in restraint in private-sector consumption and investments. A neoclassical model called dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) (*1) is effective in analyzing the economic welfare cost with such private-sector responses taken into account.

Using a DSGE model, Professors Gary Hansen of the University of California, Los Angeles and Selahattin Imrohoroglu of the University of Southern California (USC) described the Japanese economy and simulated and analyzed the economic welfare cost accompanying fiscal consolidations (working paper in progress). According to their simulation, if Japan is to restore fiscal sustainability (*2) solely by increasing consumption taxes, the rate must be raised from the current 5% to 35%, and the resulting economic welfare cost will be equivalent to the permanent elimination of 1.5 percent of current consumption. They also showed that raising the consumption tax rate rather than the income tax rate is a more desirable way of achieving fiscal reconstruction.

R. Anton Braun of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta and USC Professor Douglas Joines conducted analysis using an overlapping generations (OLG) model with two different generations, i.e., working people and retired people, and suggested that Japan needs to raise the consumption tax rate to 33% in 2017 to achieve fiscal sustainability (working paper in progress).

Given the ongoing political climate strongly resistant to any increase in the consumption tax rate, it will be dauntingly difficult to raise the rate to above 30% as suggested. However, holding down the rate increase would necessitate a severe cut in fiscal expenditure, an option involving just as much political difficulty.

As such, in fiscal analysis using a general equilibrium model, we can quantitatively describe the economic welfare cost of fiscal consolidation (tax increases). However, we cannot tell what economic welfare costs will be involved in the case of fiscal failures. In the first place, none of the general equilibrium models discussed above assumes the possibility of fiscal failures. In other words, the models are designed in such a way that a rise in public debt to a designated limit automatically prompts a tax increase.

♦ ♦ ♦

In reality, however, there is a significant possibility that the government can neither raise taxes nor reduce expenditure even in the event of a rapid increase in public debt. In such a case, the central bank will ultimately have to purchase government bonds. This situation can be considered as a fiscal failure.

In their 1981 article, Professor Thomas Sargent of New York University, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in economics in October, and Professor Neil Wallace of the Pennsylvania State University theoretically demonstrated that significant inflation will occur when central banks are forced to make large purchases of government bonds as a result of continued expansionary fiscal policies. That is, as a result of large purchases of government bonds by central banks, more money will be circulated and hence prices will go up. In his article published in 2010, Professor John H. Cochrane of the University of Chicago criticized the U.S. federal government's expansionary fiscal policy after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, warning that significant inflation will result if the government continues to run a large fiscal deficit. Although these two articles differ in theoretical frameworks, they both warn that fiscal failures will cause large inflation.

When inflation occurs, financial assets held by households will decrease in value as will the government's real debt burden. The consequential effect is an income transfer from households to the government, similar to the effect of a sharp increase in the consumption tax rate. In this regard, fiscal failures are no different from fiscal consolidation; even if the government postpones fiscal consolidation, the end result will be an income transfer to the government. However, this is tantamount to transferring income from households with government bonds and other financial assets to those without, and thus, from this alone, we cannot draw the conclusion that there will be negative impact on the economy at the aggregate level.

What we must consider here is that large inflation distorts economic activity. That is to say, it is important to measure the potential negative impact that inflation caused by fiscal failures will have on economic welfare. However, there seems to be no consensus among researchers on the quantitative evaluation of high inflation. This is because the general premise is that advanced economies have low inflation, and therefore large inflation as a result of fiscal failures has just not been assumed as a possibility. There exist some models designed to describe high inflation economies, such as those in Central and South America. However, loss functions for these models have been estimated by assuming in an ad hoc manner (provisionally) that a rise in the inflation rate results in a significant cost to the economy. An article written by Professor Guillermo Calvo of the University of Maryland in 1988 is one such example.

Apart from inflation, we cannot afford to overlook the fact that banking crises, such as the one engulfing Europe at the moment, can be induced by fiscal failures. In countries that have fallen into fiscal failure, inflation occurs and government bond prices drop, dealing a severe blow to the balance sheets of banks holding government bonds. As a result, banks would squeeze lending and/or bank runs could occur, causing a severe contraction of economic activity. Our challenge going forward is to develop a model describing an economy with these characteristics.

In any event, we must show the expected magnitude of the economic cost of fiscal failures. Otherwise, we cannot make a persuasive argument for the need to raise taxes in order to avoid fiscal failures. Should the economic cost of fiscal failures turn out to be smaller than that of tax hikes, the conclusion would be that governments should opt for fiscal failures without attempting to restore fiscal stability.

♦ ♦ ♦

Now, many of the existing studies on fiscal problems in Japan and the United States have used a closed economy model, giving little consideration to the impact that fiscal problems may have on international trade and capital flows through foreign exchange rates. As a general rule, inflation corresponds with the weakening of the currency. Meanwhile, fiscal failures cause high inflation. Therefore, as a country gets closer to the brink of fiscal failure, its currency usually declines in value. Once the currency depreciates to a sufficiently low level, the country's exports increase and economic performance bounces back.

Such, however, is not the case for Japan, where the relationship between fiscal problems and foreign exchange rates has been quite peculiar.

Today, the Japanese economy is mired as companies—exporters in particular—continue to suffer from a rising yen. At the same time, Japan's public debt, which is already at the worst level among advanced economies, is continuing to rise. Obviously, the current fiscal structure is not sustainable and the risks of facing high inflation and a sharp depreciation of the yen in due time are very high. This combination of the record high yen at the moment and the high risk of sharp depreciation in the future is the unique characteristic of the relationship between Japan's fiscal problems and foreign exchange rates.

As a possible way of addressing this situation, we can consider implementing measures designed to alleviate the risk of a drastic swing in the yen's value from appreciation to depreciation. This is discussed in more detail in my forthcoming book co-authored with Kazumasa Oguro, associate professor, Hitotsubashi University. In a nutshell, if the Japanese government sector issues a large amount of yen-denominated bonds and purchases the same amount of foreign assets (those denominated in foreign currencies), we can expect that both the ongoing appreciation and future depreciation of the yen will be alleviated. In terms of its impact on the government's balance sheets, this is the same as foreign exchange market intervention by selling yen for foreign currencies and works to correct the appreciation of the yen. Also, by increasing the holdings of foreign assets now, the government will be able to reap foreign exchange gains and improve fiscal conditions when the yen weakens in the future. This works to reduce the risk of future depreciation.

At the meeting of the National Strategy Council held last month, Kazumasa Iwata, president of the Japan Center for Economic Research, proposed that the Japanese government set up a fund worth about 50 trillion yen to purchase foreign currencies. It may be necessary for Japan to formulate, through such various thought experiments, a new policy scheme that combines measures to prepare for possible fiscal failures and those to address foreign exchange problems.

* Translated by RIETI from the original Japanese "Keizai kyoshitsu" column in the November 7, 2011 issue of the Nihon Keizai Shimbun.

Keywords

- Neo-classical general equilibrium model

In order to perform an accurate cost and benefit analysis of fiscal reconstructions, we need to know how households and businesses change their behavior in response to changes in government policies. The traditional macroeconomic model (Keynesian model) assumes that households and businesses do not change their behavioral patterns even if the government changes its policies. In contrast, the neo-classical general equilibrium model attempts to describe, based on microeconomic theories, how various economic entities change their behavioral patterns in response to policy changes, thereby explicitly showing how such behavioral changes affect macroeconomic variables such as consumption, employment, and investment. This model is typically used by the monetary authorities in analyzing the effect of monetary policy. - Fiscal sustainability

A country is considered as fiscally sustainable when public debt as a share of GDP is not expected to increase indefinitely in the future. The country becomes fiscally unsustainable if it continues to run fiscal deficits in a situation where the nominal GDP growth rate is lower than the nominal interest rate.

Event Information

Fellow titles and links in the text are as of the date of publication.

For questions or comments regarding RIETI Report, please contact the editor.

*If the "Send by mailer" button does not work, please copy the address into your email "send to" field and connect the prefix and the suffix of the address with an "@", sending it normally.RIETI Report is published bi-weekly.