Five years have passed since the start of unconventional monetary easing by the Bank of Japan (BOJ). Even recently, the growth rate of consumer prices has remained close to zero, which means that Japan is still stuck in deflation. However, over the five years of monetary easing, we have learned, to some degree, how Japan has become trapped in deflation.

The greatest lesson is that deflation is caused by a supply-side factor, rather than a demand-side one. Supply-side factors are related to the attitudes of companies which price products. In the early days of the unconventional monetary easing, many people predicted that Japan would be able to overcome deflation if only demand was increased. Indeed, some numerical indicators, such as the unemployment rate, improved, but the improvement did not spread to prices. That is because many companies have been unable to pass on a cost increase to prices.

♦ ♦ ♦

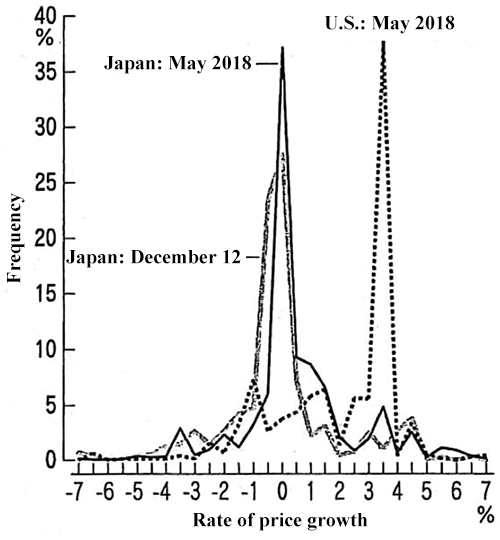

The Figure shows a frequency distribution of year-on-year changes in the prices of around 600 product items that constitute the consumer price index. In the United States, the peak frequency (maximum frequency value) is 3.5%. In other words, the companies' default attitude is to raise prices by 3.5% each year. A majority of companies behave in that way. In the United States, the maximum frequency value was around 2% even during the financial crisis, and in most other developed countries, the maximum frequency value has remained positive.

On the other hand, in Japan, the maximum frequency value has remained zero, as it did before the start of the unconventional monetary easing. The frequency is close to zero for around half of all items. In Japan, keeping prices unchanged became the default attitude in the late 1990s, and this attitude has continued ever since.

In my view, the practice of keeping prices unchanged has become entrenched because the government and the BOJ have left deflation unattended for an extended period of time. As deflation took hold, consumers started to take it for granted that prices should remain unchanged and became intolerant of even slight price increases. As companies were worried that they might lose many customers if they raised prices even a bit, they began to swallow cost increases and keep prices unchanged.

How does the practice of keeping prices unchanged affect the economy? The hashtag #kuimon minna chiisaku natte massenka Nippon (which literally means: "Is every food product in Japan shrinking?") is very instructive in this respect. Social networking service (SNS) sites are abuzz with comments concerning products whose prices have remained unchanged but which have become smaller in volume. Such cases of virtual price hikes have increased since 2013 against the backdrop of the yen's depreciation due to the unconventional monetary easing and the rising labor cost.

Shrinking the sizes of products involves various costs, including the cost of changing the production line layout. In other words, the shift to a smaller size has undesirable effects not only for consumers but also for companies. Companies pursue a smaller size even at an additional cost because they are fearful that they would never be able to raise sales prices openly.

100-yen shops represent a typical business model based on the practice of keeping prices unchanged. It is possible to develop novel products while keeping their prices unchanged at 100 yen, which has been the key to the success of 100-yen shops. However, from this business model, we cannot anticipate the arrival of the manufacture of innovative new products that would cost far more than 100 yen. Likewise, from companies bound by the "no price change" practice, forward-looking product development or investment cannot be anticipated.

♦ ♦ ♦

What should be done to do away with the no price change practice? The BOJ's monetary easing has the effect of pushing up companies' costs, for example, through the yen's depreciation and a labor cost increase. If the cost increase is passed on to prices, prices will rise. However, if the current circumstances continue, that is unlikely to occur. The important thing to do is improve an environment that enables companies to pass on cost increases to prices, rather than raising costs.

According to a questionnaire survey conducted in May 2018 by the University of Tokyo's Center for Advanced Research in Finance, while 17% of the respondents do not like the price increase for door-to-door parcel delivery services because of unfavorable effects on their lives, 74% regard some degree of increase as inevitable because door-to-door parcel delivery companies appear to be struggling. The results indicate that consumers understand the companies' difficult situation.

As is clear from the above example, whether or not companies can successfully pass on a cost increase to prices depends on whether they can gain sympathy from customers. Shrinking the product size is also called a "stealth price increase." This name represents companies' effort to virtually raise prices without being noticed by consumers. With an attitude like this, companies cannot gain sympathy from consumers. Companies should be ready to explain candidly why they need to raise prices.

One possible measure to develop an environment that makes it easier to pass on a cost increase to prices is changing the consumption tax rate. According to a study by Toshiaki Shoji, a member of our research team, prices rose by a margin larger than the increase in the consumption tax rate for most foods and daily products at the time of the consumption tax rate hike in 2014. When the consumption tax rate changes, all companies need to revise prices including the consumption tax rate. The consumption tax rate hike in 2014 is likely to have encouraged companies to pass on the cost increase that they had previously swallowed themselves at the same time as revising prices to reflect the tax rate hike.

Harvard University Professor Martin Feldstein et al. has proposed that the consumption tax rate should be raised several times in small increments. If the consumption tax rate is raised by one percentage point or so per year several times instead of by several percentage points at a time, for example, companies are expected to become less fearful about passing on a cost increase to prices. However, in that case, it would be essential to make up for a decline in the purchasing power due to the consumption tax rate hikes. It is also worth considering the idea of implementing several income tax reductions on a similar scale.

Whatever policy measure may be taken, it is difficult to accurately predict the results, so trial and error is inevitable. We must be prepared for the prospect that it will take some more time for the no price change practice to be corrected.

♦ ♦ ♦

The next point that we should consider is how we should evaluate the BOJ's inflation target of 2% growth in consumer prices. One reason why the inflation target has been set at 2%, rather than zero, is the presence of measurement errors in price statistics. At the moment, the error is around 0.5%, which is a negligible level.

The most important factor behind the decision to set the inflation target at 2% is the need to leave room for policy flexibility. If the inflation rate is kept at a relatively high level in normal times, nominal interest rates can also be kept relatively high. This secures room for monetary easing in times of emergency.

However, this policy flexibility mechanism is not functioning well at the moment. Harvard University Professor Lawrence Summers has warned that developed countries are not well prepared for future crises. The policy interest rate in the United States still remains low, so room for implementing monetary easing in the event of an emergency is restricted. The situation is even more difficult in Europe and Japan. In Japan in particular, there is no room for either monetary easing or fiscal stimulus.

What is important is not achieving 2% inflation growth but preparing for future crises. What should be done to prepare for future crises? Japan's unconventional monetary easing has its roots in the adjusted inflation scheme that has been advocated by City University of New York Professor Paul Krugman. As goods become more attractive in terms of price in the future due to deflation, the value of the currency also increases. To reduce the future value of the currency, it is necessary to raise future prices compared with the present level. Controlled inflation is supposed to do that.

However, there is a more effective way of reducing the future value of the currency: changing the exchange rate between the present and future values of the currency. Usually, the exchange rate between the present and future values of the currency is 1-to-1. If the rate is changed in such a way that the present 10,000 yen will be worth 9,900 yen in the future, that will achieve the same effect as the effect of a 1% controlled inflation. This is equivalent to imposing a negative interest of 1% on banknotes.

So long as paper currency is used, it is difficult to impose interest on the currency. However, it will become possible to do so if the central bank introduces a currency scheme similar to Sweden's e-krona project, and interest is imposed on digital currency. Introducing digital currency will be a powerful defense against future crises.

There is a precedent in Japan in the 1970s of considering controlled inflation as an option. At that time, it was proposed that prices in Japan should be set at a high level compared with U.S. prices in order to make the yen less attractive relative to the dollar. However, as the idea of creating high inflation faced strong resistance, the government chose to raise the yen's exchange rate instead of implementing controlled inflation and ultimately abandoned the fixed exchange rate system.

At that time, considering measures such as raising the yen’s exchange rate and abandoning the fixed exchange rate system was viewed as taboo. Likewise, considering changing the exchange rate between the present and future currencies is now seen as taboo. However, given that the prospects for raising the inflation rate are dim, the government and the BOJ should start considering the unthinkable measure as a policy option.

* Translated by RIETI.

July 19, 2018 Nihon Keizai Shimbun