With one year until the planned consumption tax rate hike, attention is focusing on its impact on consumption once again.

In this article, the author will examine the impact of the consumption tax rate hike on consumption based on joint research conducted with David Cashin, a senior economist at the Federal Reserve Board of Governors (FRB). From these pieces of research, it has become clear that the impact on consumption can be broadly divided into three effects and that the effects arise at different timings.

♦ ♦ ♦

In the field of economics, it is assumed that consumption is determined on the basis of the Life Cycle/Permanent Income Hypothesis (LCPIH). According to the LCPIH, consumers try as much as possible to keep their household consumption level stable because they do not like flactuations in their consumption. However, it is also assumed that if a future change in the economic environment is expected, they will change their consumption level accordingly. In particular, if an increase in lifetime disposable income is expected consumers increase their household consumption, and if a decline is expected, they reduce it. They also change their consumption level when a change in general prices is expected: if a price rise is expected, they increase their consumption until prices actually rise, and vice versa.

Under this hypothesis, there are two effects through which the consumption tax rate hike may affect consumption.

One is the income effect, which arises through a decline in lifetime disposable income due to the tax rate hike. When the consumption tax rate is increased, prices will rise by the same margin as the margin of the tax rate hike. Given all other conditions constant, real lifetime disposable income will decrease by the same margin, and real consumption expenditure will also decline by the same margin due to lifetime budget constraints. This is known as the income effect. Set aside more complicated factors such as the application of a reduced tax rate and the presence of tax exempted items, the planned tax rate hike from 8% to 10% is supposed to bring a decline of 1.8% in real consumption expenditure.

This point is often misunderstood; it is not nominal consumption expenditure as measured by prices including the consumption tax but real consumption expenditure as measured by real prices adjusted for the consumption tax rate hike that declines. It should be kept in mind that consumption tax revenue increases by a margin commensurate with the margin of the tax rate hike.

The other effect is a change in consumption behavior in response to a price change due to the tax rate hike, which is known as the intertemporal substitution effect. The effect, which arises as consumers increase their household consumption level while prices are low, keeps the level of consumption high before the tax rate hike and brings it down after the hike.

In addition to these two effects, the consumption tax rate hike may also affect consumption in a way that is not taken into consideration under the LCPIH. Just before the consumption tax rate hike is implemented, last-minute demand surges to be followed by a rebound decline after the implementation. We call this the "arbitrage effect." This effect arises because of households' inclination to hoard products before prices rise, a kind of "expending" behavior observed only with respect to durable goods and goods that can be stockpiled.

This is not a matter of consumption decision but a matter of stock adjustment, so to speak. This effect is stronger when the date of the consumption tax rate hike is closer, when the cost of storing the product is smaller, and when the pace at which the technology becomes obsolete is slower.

The arbitrage effect is similar to the intertemporal substitution effect in that both effects are attributable to households' response to a price change. However, the arbitrage effect is different from the intertemporal substitution effect in that it causes expenditure, but not consumption itself, to change. Another major difference is that whereas the intertemporal substitution effect is permanent after a price rise, the arbitrage effect disappears when the accumulated stocks are used up.

♦ ♦ ♦

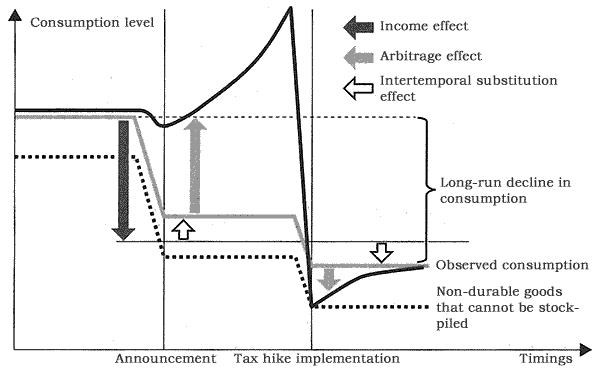

The above three effects do not arise at the same time as the implementation of the consumption tax rate hike. The figure below shows when each of these effects may affect consumption and in which way. The two key timings are when consumers recognize the prospect of higher tax (announcement) and when the consumption tax rate is actually raised (tax hike implementation).

When consumers have recognized an expected decline in lifetime income, the income effect immediately reduces household consumption level on a permanent basis (the effect indicated by the black arrow). On the other hand, the intertemporal substitution effect increases consumption level at the time of announcement and reduces it at the time of tax hike implementation (the effect indicated by the white arrow). The consumption trend concerning non-durable goods that cannot be stockpiled is determined by these two effects (indicated by the dotted line).

If the normal consumption of durable goods and goods that can be stockpiled is added to the consumption level represented by the dotted line, it represents a rough benchmark of consumption level (indicated by the gray line). However, the arbitrage effect will cause last-minute demand starting at the time of announcement, resulting in an increase in consumption level compared with the normal level. After the tax hike implementation, this effect will keep the consumption level low for a while, but it will gradually fade away and eventually disappear entirely (indicated by the gray arrow).

From the figure, it is clear that the income effect and the intertemporal substitution effect are factors that depress consumption in the long-run. Furthermore, our research has empirically confirmed that the elasticity of the intertemporal substitution effect regarding Japanese households is sufficiently weak. This means that a change in consumption level due to the intertemporal substitution effect may be ignored. In other words, the income effect is the most important effect caused by the consumption tax rate hike.

However, in considering how to counter the impact of the consumption tax rate, the government is focusing only on measures to mitigate the arbitrage effect, such as providing tax breaks related to housing and automobiles and removing a ban on discount sales offered explicitly for the purpose of offsetting the tax hike. This policy response reflects a misunderstanding where a rebound decline in consumption level after the tax hike implementation is regarded as the main culprit of tax hike-related consumption slump.

From the figure, we can also understand why misunderstanding arises with respect to the cause of consumption slump. Although the figure shows how each of the three effects works, what can be observed in the real world is their combined result, which is indicated by the black line. At the time of announcement, not only the income effect but also the intertemporal substitution effect and the arbitrage effect in the form of last-minute demand will arise, so the change in the consumption level that will be observed will be small.

On the other hand, at the time of tax hike implementation, a steep decline in consumption level will be observed as a result of the intertemporal substitution effect and the rebound decline. After the rebound decline has run its course, the consumption level will appear to be lower than the level immediately before the announcement, creating the wrong impression that consumption level is not recovering from the rebound decline.

If the government is worried about the impact of the consumption tax rate hike on consumption, it must consider measures to counter the income effect, rather than the arbitrage effect. However, as it is impossible to prevent real income from falling due to the tax rate hike, a decline in consumption level cannot be avoided, either.

♦ ♦ ♦

How should the government counter the income effect? We can find clues to the answer in the difference between the results of the consumption tax rate hikes in 1997 and 2014.

According to our research, at the time of the tax hike in 1997, the income effect was not detected, while a steep drop in consumption level due to the income effect was observed in 2014. This difference can be explained by the fact that the income effect arises when individual consumers recognize the prospect of higher tax.

Although a consumption tax rate hike is implemented at the same time nation-wide, the timing of recognizing the prospect of higher tax varies by individuals. If most consumers recognize the prospect of higher tax simultaneously, consumption level is expected to decline steeply then. On the other hand, if that timing varies, the timing of the decline in consumption level is expected to vary, preventing a steep decline in overall consumptions. In short, the most effective way to keep consumption level stable is not by eliminating the income effect but by making it invisible by diffusing it over time.

The 1997 tax hike was determined more than two years before the implementation, and after some twists and turns, it was eventually implemented as scheduled. During the protracted waiting period, the prospect of higher tax gradually penetrated into the consciousness of the Japanese people, so the income effect was diffused over time sufficiently to become invisible. In contrast, at the time of the 2014 tax hike, the hike was announced in a dramatic way by the prime minister at a press conference just as expectations for the cancellation or postponement of the measure were growing. As a result, most consumers apparently recognized the prospect of higher tax simultaneously. Indeed, data on the trend in consumption of non-durable goods that cannot be stockpiled, such as fresh foods, showed a steep drop in October 2013, when the announcement was made.

At this time, as the planned tax rate hike has already been postponed twice, it is unlikely that the recognition of the prospect of higher tax has been well established among the Japanese people. However, if the government continues to suggest the possibility of another postponement but eventually announces the tax rate hike shortly before the implementation, consumption level may decline steeply once again.

As consumption has recently remained relatively stable, it is possible under the current circumstances to diffuse the income effect over time. The best step that the government can take to keep consumption level stable is to commit itself to the tax rate hike as early as possible so that the prospect of higher tax can steadily penetrate into the consciousness of the Japanese people.

* Translated by RIETI.

September 26, 2018 Nihon Keizai Shimbun