Polarization is growing in Japan as disparities between rural and urban areas become more pronounced. While the population of rural prefectures has significantly decreased over time, for instance, dropping below one million in Akita prefecture, the number of those living in central Tokyo has been on the rise. The population of Setagaya ward alone, totaling approximately 900,000, exceeds that of Tottori or Shimane prefecture.

In a bid to rectify the ongoing unipolar concentration in Tokyo, the government has been taking steps to vitalize rural economies, bringing in more people and generating local jobs. In FY2017, it earmarked 100 billion yen in grants for promoting selected local revitalization initiatives, i.e., those regarded as trailblazing and undertaken by local municipalities in a self-motivated and self-directed manner. Meanwhile, under its fiscal plan for local governments, one trillion yen in the national budget was allocated to rural revitalization projects—those designed to invigorate local economies, tackle depopulation, and create jobs—and reflected in the way of distributing local allocation tax grants, which are subsidies from the central to local governments.

The former is designed to help hard-working municipalities, enabling them to mobilize the full potential of their respective regions. Likewise, the latter is meant to make a shift toward a merit-based allocation to distribute more funds to municipalities making progress, for instance, in their efforts to increase labor force participation among young people, in view of the need to provide assistance to regions suffering depopulation. The government also introduced a top-runner approach into the calculation of local allocation tax grants to set the standard unit costs of certain types of public services based on the actual unit costs in the best-performing municipalities in the level of outsourcing and other cost-efficiency measures. All of these schemes aim to provide an incentive to encourage self-help efforts on the part of municipalities.

However, those making self-help efforts are not the only ones getting support, as the government has pledged to ensure that necessary financial resources be secured for those municipalities defined as "disadvantaged" and thus unable to improve efficiency. All told, the mechanism remains the same in that the government gives due consideration to all of the municipalities so that none of them will be left out, regardless of the degree of their efforts.

♦ ♦ ♦

The government invariably provides municipalities with an extensive and solid guarantee of financial resources. The government is committed to such a guarantee at a macro level (vis-à-vis all of the municipalities as a whole) as well as at a micro level (vis-à-vis individual municipalities). The fiscal plan for local governments calls for an allocation of an amount equal to the sum of the necessary expenditures estimated by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications for all of the municipalities as a whole. However, contrary to what the term may imply, there is no scientific or objective evidence showing the necessity of such expenditures. Rather, they are typically based on past allocations and expenditures and reflect the central government's intentions, for instance, with respect to economic stimulus measures. The expenditures include not only those for policy implementation—e.g., social security, infrastructure development, and education—but also those to cover the cost of servicing local government bonds. Local government expenditures budgeted for FY2017 amount to 86.6 trillion yen. This includes local expenditures not covered by the central government and thus cannot be directly compared against the size of the central government's budget. Still, it is worth noting that the amount accounts for nearly 90% of the actual amount of the central government's general account expenditures in FY2016.

Local government expenditures in excess of the sum of local tax revenues, purpose-specific subsidies from the central government, and proceeds from the issuance of local government bonds are covered by local tax allocation grants, i.e., non-purpose-specific subsidies from the central government. Fixed percentages of five national taxes, including the income and consumption taxes, are set aside for funding local tax allocation grants. However, amounts thus allocated to local governments have been falling below the amounts required to make up for their revenue shortfalls.

The remaining gaps are filled with additional funds channeled from the central government's general account or proceeds from the issuance of deficit-covering local government bonds. In the latter case, the cost of servicing such bonds will be included in the necessary expenditures under the central government's fiscal plans for local governments, hence, covered by local tax allocation grants in the subsequent years. As such, local government bonds are backed by the central government's guarantee of financial resources rather than the financial capacity of the respective issuing municipalities. The amount of local allocation tax grants apportioned to a specific municipality is determined based on the difference between the municipality's "standard fiscal demand," which refers to the pro-forma cost of administrative services supposed to be covered by general revenue (local tax allocation grants and local tax revenue), and the "standard fiscal revenue," which refers to the estimated financial capacity of the municipality.

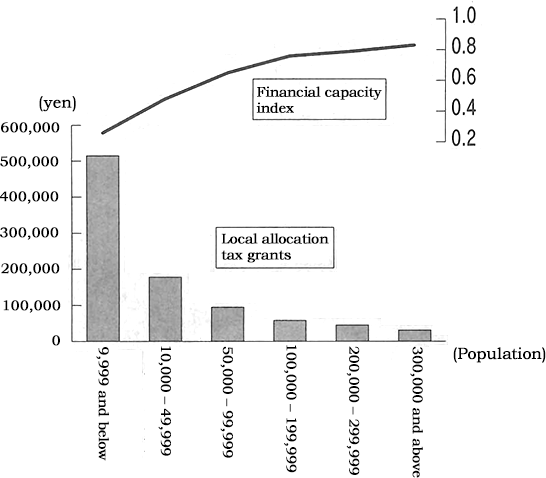

The standard fiscal demand includes the amount of the above-discussed incentive allocations. However, there is no denying that local allocation tax grants operate more as a rescue scheme for needy municipalities than as an incentive scheme. The standard fiscal demand reflects the cost of servicing deficit-covering local government bonds and tends to inflate when administrative services are costly as typically is the case with small-sized municipalities. Indeed, the financial capacity index, calculated as the ratio of the standard fiscal revenue to the standard fiscal demand, is low for municipalities with small populations, meaning that they have difficulty in securing necessary financial resources to cover the cost of administrative services on their own. The government allocates huge amounts of local allocation tax grants to enable them to secure sufficient financial resources (Figure).

Local allocation tax grants have been made available in such way as to allow local governments to provide standard public services deemed necessary by the central government. This has been blamed as contributing to municipalities' chronic dependence on local tax allocation grants and impeding their fiscal discipline.。

♦ ♦ ♦

Municipalities have their side of the story. Regardless of their size and financial capacity, they have implemented policy measures—including those for social security and education—under the intervention of, or as imposed by, the central government. Policy measures undertaken by municipalities are basically the same across the country, although there are some differences in the scope of administrative duties for city planning and welfare services between municipalities designated as "core cities" or "ordinance-designated cities" and the others. Local allocation tax grants as a guarantee of financial support for municipalities are meant to ensure the smooth implementation of such uniform policy measures. The central government's responsibility as a guardian for municipalities is the reverse side of its significant intervention in and imposition of local policy measures.

However, as the central government's fiscal health deteriorates, local allocation tax grants as a financial guarantee mechanism are getting wobbly. The central government has pledged to maintain the current level of general revenue resources for municipalities in terms of the total amount (i.e., approximately 60 trillion yen), but the sustainability of the plan is questionable. Some members of the government's Council on Economic and Fiscal Policy have pointed out that fund reserves held by municipalities total 21 trillion yen. According to them, municipalities reserving a large amount of funds relative to the size of the standard fiscal demand are characterized by weak financial capacity and a large percentage of elderly people aged 65 and above. This may indicate that municipalities heavily dependent on local allocation tax grants are trying to safeguard against the risk of diminishing financial support from the central government.

The central government might be making every effort so as not to put any single municipality in trouble, but the sense of distrust is growing on the part of municipalities. This is identical in pattern to the backfiring of social security programs, in which a mechanism designed to provide people with a sense of security about their future is causing people to worry about their future and spend less today (save more for the future).

♦ ♦ ♦

What can and should be done to change the situation? In what follows, I would like to propose two reform steps: 1) public services provided separately by cities, towns, and villages should be combined to cover broader geographical areas or transferred to the relevant prefectures, and 2) the existing financial resource guarantee mechanism of local allocation tax grants should be reformed.

Cities, towns, and villages are the smallest administrative units that provide a range of day-to-day public services to their residents. As such, they have been perceived to be the ones positioned to accept more authority, responsibility, and functions in decentralization. Indeed, when the central government vigorously promoted municipal mergers from 1995 through March 2010, the intention was to strengthen the financial base of municipalities as the smallest administrative units. However, it has now become apparent that not all of the municipalities are capable of fulfilling the same role because of depopulation and aging. Unless more mergers occur among cities, towns, and villages, it will be inevitable to combine service areas to improve the efficiency of expenditures and secure the supply of public services.

According to the Development Bank of Japan, the number of people served by a water supply utility must be no less than 50,000 in order to reduce amounts transferred from the municipality's general account to the utility to make up for its deficit. Water supply and other services offered by public corporations and a range of other public services such as healthcare, industry promotion, public transportation, infrastructure development, and tax collection (particularly from delinquent taxpayers) should be coordinated by prefectures or undertaken by core cities. The government's Basic Policy on Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform 2017 calls for steadily promoting initiatives by local municipalities to provide public services jointly to cover a broader geographic area, in particular, noting that cities, towns, and villages with small populations and limited financial and administrative capabilities should partner up with their nearby core city or prefecture. As policy interventions in support of such efforts, the government has put in place two programs, one designed to promote permanent relocation from urban to rural areas and the other to facilitate the formation of local metropolitan areas, each comprising a central city as a pivot and a groups of smaller municipalities as its satellites. Municipalities across the country should make better use of these programs.

The perception of cities, towns, and villages as major players in decentralization must change. Starting from FY2018, prefectural governments will operate the national health insurance programs, taking over the roles currently served by cities, towns, and villages. Prefectures will also assume other functions from those cities, towns, and villages that are limited in financial and administrative capabilities. There may as well be some options to choose from to allow municipalities to take a step forward voluntarily, rather than forcing them to move in a certain direction. Decentralization should be able to take diverse forms in the future.

The government should change the criteria for distribution of local allocation tax grants, i.e., the method of calculating the standard fiscal demand. Up until now, the government has given extra amounts to small, depopulated municipalities in distributing local allocation tax grants. These municipalities are also subject to special consideration in the allocation of national budget earmarked for rural revitalization projects. However, the system for distributing local allocation tax grants should have simpler criteria and be neutral with respect to municipalities' choice concerning partnerships with other municipalities in providing public services or transferring such functions to the prefecture, rather than being a financial guarantee mechanism to enable even the smallest municipality to get by.

Improving the efficiency of expenditures by municipalities would reduce their deficits or amounts to be covered by local allocation tax grants, enabling the central government to better focus on those municipalities that are located in mountainous areas or on remote islands and thus unable to partner up with other municipalities. The government needs to rebuild its fiscal program for local governments into one that can properly address the needs of new economic and social realities of shrinking rural economies with decreasing populations.

* Translated by RIETI.

September 29, 2017 Nihon Keizai Shimbun