Japanese taxpayers shifted more than 165 billion yen in their local tax payments as donations to their selected municipalities in FY2015 under the so-called furusato nozei or "hometown tax" donation program. The amount more than quadrupled from the previous fiscal year and represents approximately 20 times that in FY2008, the initial year of the program. The underlying philosophy of the program is to enable taxpayers to support municipalities of their choice. It has been hoped that the program would serve as a showcase opportunity for municipalities to attract people's attention to their efforts or initiatives, because they can specify the purpose or project for which they ask for donations. However, what we see in reality is far removed from that philosophy.

To be sure, the program played a significant role in supporting municipalities affected by major disasters such as the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011 as well as the Kumamoto earthquake and the Itoigawa fire in 2016. However, in ordinary times, municipalities are trying to garner donations by offering generous return gifts, while donor taxpayers typically choose municipalities that offer their preferred return gifts, rather than those to which they want to give support. As such, the hometown tax donation program is more like a government-subsidized mail order business than a donation program.

♦ ♦ ♦

Why have we gotten into this situation? One big factor behind this is the structure of the program, i.e., how it is designed to operate.

Taxpayers making donations under this program can have the entire amount donated less 2,000 yen deducted from the amount payable in national and local income taxes. More specifically, in addition to ordinary donation deductions from taxable income, they can claim a special tax credit of up to 20% of the amount of local income taxes (i.e., the income-based portion of local taxes), together reducing the overall tax amount by the amount donated less 2,000 yen. Thus, the effective burden borne by each donor taxpayer is just 2,000 yen.

Now, suppose that a taxpayer donates 10,000 yen to a certain municipality and receives a return gift worth 6,000 yen. This is tantamount to making a purchase worth 6,000 yen just for 2,000 yen. The recipient municipality makes a net gain of 4,000 yen after the cost of the return gift. Meanwhile, the municipalities (e.g., city and prefecture) in which the taxpayer resides and the central government lose 8,000 yen in their combined tax revenue.

The hometown tax donation program has been serving as a tax saving tool biased in favor of middle- and high-income earners because the maximum amount of tax credit deductible (20% of the amount of local income taxes) increases in proportion to the amount of annual income. For instance, the ceiling for a single-person household with annual income of 3.5 million yen is only 34,000 yen, compared to approximately 400,000 yen for that with annual income of 15 million yen. This means that those earning more money can purchase more products—local specialties or else—just for 2,000 yen.

Local taxes are meant to be payments in consideration for services rendered by local governments (benefit principle). While many households pay taxes based on this principle, middle- and high-income earners have been able to avoid their tax obligations and receive generous return gifts by taking advantage of the program. The program is unfair in the sense that the benefit of tax reductions concentrates on middle- and high-income earners.

♦ ♦ ♦

Gift-offering competition among municipalities is escalating. Items offered are not limited to local specialties and include gift certificates and home electric appliances. In extreme cases, the list of return gifts for big donors includes mobile tablet devices and drones. Some cities began to accept hometown tax donations from local residents, finding a loophole to exploit in the program, i.e., hometown tax donations are deductible in calculating income taxes payable not only to the city in which a donor taxpayer resides but also to the national and prefectural governments, leaving the city with room to gain from donations from its residents.

In the wake of these developments, the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications has been urging municipalities to "respond with good sense in due consideration of the intended purpose of donation deductions," for instance, by refraining from offering gift certificates and other items that are easily exchangeable for cash. However, taken as a whole, the competition is showing no sign of subsiding. According to the ministry's survey report released in June 2016 on the current state of hometown tax donations, roughly 60% of the municipalities nationwide cited "enhancing gift options to choose from" as a priority area of their efforts to solicit donations from taxpayers. In contrast, only less than 30% cited "increasing clarity about the use of funds donated and/or enhancing project options to choose from."

From the viewpoint of municipalities, this is a natural consequence. A municipality cannot increase the amount of donations by offering modest return gifts when neighboring municipalities are offering pricey ones. Even worse, if its residents donate to other municipalities, it may end up with reduced revenue. Thus, municipalities have no choice but to compete, rather than competing at their own will.

It is generally expected that decentralization will stimulate competition among municipalities. However, not all competition is good. The kind of competition that results in the creation of new value added through friendly competition and mutual learning is good. However, when players seek to gain at the cost of others as in a zero-sum game, it is bad competition. Gift-offering competition is a typical example of the latter.

The resulting consequence of this competition, which may be the spiraling cost of return gifts or else, is not a desirable one. In fact, the cost of procuring and sending return gifts amounted to 67 billion yen in FY2015, accounting for 40% of the total amount of taxes donated.

One of the intended goals of the hometown tax donation program is to address inter-regional disparities by channeling funds from urban cities to rural municipalities.

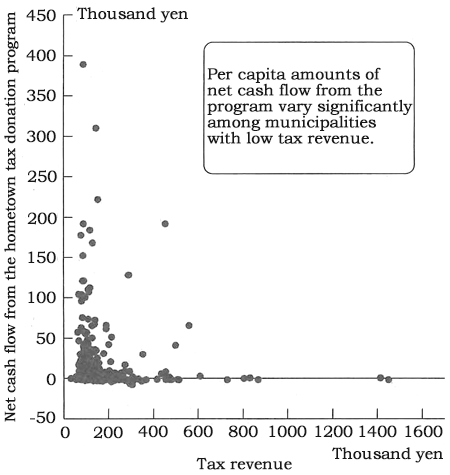

The figure below shows the relationship between the per capita amount of tax revenue for each municipality in FY2014 and that of net cash flow resulting from the hometown tax donation program in FY2015. Net cash flow from the program represents the amount of tax donations received by each municipality less the amount of local taxes foregone due to tax donations made by its residents to other municipalities. Per capita amounts of net cash flow from the program vary significantly among municipalities with low tax revenue (weak financial positions).

We can see that only some of those municipalities with low tax revenue have emerged as winners, indicating that the hometown tax donation program has not led to systematic reductions in interregional disparities.

♦ ♦ ♦

There is a risk of distorting Japan's donation culture. In a bid to create a vibrant society driven by the spirit of mutual assistance, the government has been trying to foster a donation culture by expanding tax incentives. By definition, donation is the act of giving money, without expecting anything in return, to help the cause or activity one wishes to support. The level of willingness to donate among Japanese people remains low. The hometown tax donation program, as it stands today, could spread the misperception that it is only natural to receive something in making donations, while what the government should be doing is to foster a positive public attitude toward charity giving.

The program could also hamper the efforts of some philanthropic organizations—i.e., those that are making significant contribution to society but financially weak—making it even more difficult to raise funds. In such a situation, there is no developing a donation culture in Japan. Also from the viewpoint of municipalities, the program will not be in their interest in the long run, because soliciting donations by offering return gifts does not lead to winning true supporters. When other municipalities also offer attractive return gifts, there is no securing a stable source of donations.

The program is not necessarily beneficial even to those local businesses producing return gifts. In some municipalities, the program has had significant influence on business decisions, for instance, prompting a seafood company to set up a new processing plant to respond to a sudden increase in demand for its products, which turned out to be popular return gifts. In another case, the amount of locally grown rice distributed through the existing sales channel was reduced to be used as return gifts. However, when the boom is over, the seafood company may end up with excess capacity and massive debt and rice growers may not be able to regain access to their previous sales channels.

Some people say that the hometown tax donation program is offering rural municipalities a superb opportunity to promote local specialties to consumers nationwide. However, the boom in demand for those products that are popular only because they cost a mere 2,000 yen is unlikely to last long. What they should be doing instead is to increase the competitiveness of their products to make them sell well at market prices. The popularity of some local specialties as return gifts for donor taxpayers is nothing more than government-created demand. Regional development reliant on such subsidized demand is not sustainable.

Then, what should we do? The current program treats donation and the offering of return gifts as separate acts, thus allowing taxpayers to claim the special credit based on the entire amount donated regardless of whatever return gifts they receive. In order to put the brakes on excess gift-offering competition, an amount equivalent to the value of return gifts should not be deductible in calculating national and local income taxes.

In the case of the aforementioned example in which the taxpayer donated 10,000 yen, the value of the return gift, 6,000 yen, is not deductible. This reduces the effective amount deductible for this taxpayer to 2,000 yen, calculated as 10,000 yen donated less 6,000 yen for the return gift and a non-deductible threshold of 2,000 yen. In a bid to contain escalating competition, the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications has notified municipalities nationwide that the value of return gifts must not exceed 30% of the amount received in tax donations. The government has finally begun reviewing the program.

Furthermore, in a medium- to long-term perspective, the government should reduce and abolish the special credit for hometown tax donations to bring those donations to municipalities into equal footing in tax treatment with donations to other organizations including non-profit organizations. Hometown tax donations, including those to disaster-affected municipalities, should return to the initial philosophy or intended purpose of the program.

* Translated by RIETI.

April 7, 2017 Nihon Keizai Shimbun