PDF version [PDF:410KB]

Introduction

It is easy to imagine that Japan's declining population will have a significant impact on all aspects of the economy and society, including social security systems as well as government finances. Even as total social security payments made to senior citizens continue to climb, the greater part of these costs will be paid for by a smaller pool of working people in the current and future generations. This means that the balance of payments, particularly for the social security system, will drastically deteriorate.

The critical point here, however, is that while a combined strategy of cutting payments and increasing the cost burden of the individual is effective in improving the balance of payments, these initiatives cannot much alleviate pressures caused by the declining population.

If payments to the elderly population are cut, elderly individuals will need to be assisted privately. Thus, working individuals would be facing an even slimmer financial margin. To fight against the pressures of the declining population, the only solution is to increase the number of those contributing to the system. In short, it is essential that older workers be employed at a greater rate.

There are, however, several points open to discussion on the question of expanding the senior worker population. In this paper, the first issue we address is just how far we can tap the potential for senior employment with regard to the question of health. Next, we address the pension system, calculating the extent of the impact of the pension system on the employment of older workers. The pension program is undoubtedly an important source of income security for the elderly, yet it is not without drawbacks in the context of senior employment, as it tends to greatly encourage the individual to retire once they receive their pension. The pension issue cannot be ignored in the context of initiatives to create a larger pool of people supporting those receiving social security benefits.

How Far Can We Expand Senior Employment?

First, let's consider the extent to which the potential of the senior citizen workforce can be expanded. Most people would think that, in order to encourage older people to continue working, we need to raise the age at which individuals can begin to take their pension. However, there is another factor to consider: as people age, they begin to experience health problems, and some may not be able to work at the same level as they did when they were younger. Upping the age when a person can claim their pension benefits may cause problems by forcing older individuals, who are not capable of doing so, to work.

Looking at the issue from the perspective of health, we have made calculations in an attempt to ascertain the maximum possible increase of the working senior population. Actually, employment rates drop precipitously around age 60. However, the reason for this is not generally due to dramatically declining health, but rather that these individuals have simply reached retirement age and are now eligible to receive pension benefits. Assuming that health is the only constraint on employment, we estimate the extent to which senior employment can be expanded accordingly.

The specifics of our estimates, based in the ideas of American economists, are as follows. First, we estimate a regression model (utilizing statistical correlations between variables) explaining employment rates of people aged in their 50s – whose employment decisions are not significantly affected by the prospect of a pension – based on actual data. Next, taking the correlation between health and employment derived from the regression, we estimate the probability of employment for each individual aged 60 and over corresponding to their state of health. The average of the probabilities of employment represents the health capacity to work. The actual employment rate is likely to fall short of the projected potential one, and the gap between the two represents the extent to which the employment rate can be potentially increased.

This approach is somewhat rough. Firstly, it assumes that the correlation between health and work is constant from the 50s age group onward. This study also ignores the impact of lifestyle changes such as divorce, death of a partner, and living with family members on decisions on work. Taking these factors into consideration, the further away the individual is from the age of 50, the greater the care that must be taken in interpreting results. At the same time, I believe this work is important in the sense that we can quantify potential increases in the older worker employment rate.

30% Rise in Employment Rate Possible for Those Aged 60–64

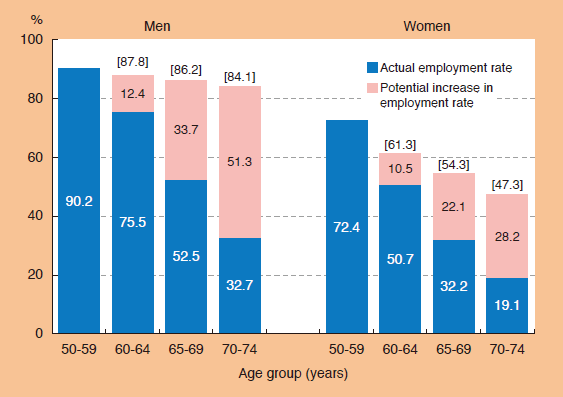

Data used in the analysis is taken from the 2016 Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions (CSLC) conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. This data set provides detailed information on an individual's health, including the presence or absence of more than 40 kinds of illnesses, psychological stress, daily life challenges, subjective views of their own health, and tobacco use. The Life Table, also provided by the ministry, which shows the average remaining lifespan by age, is used in conjunction with the above data. Chart 1 indicates major estimation results.

The CSLC shows that for men, while the employment rate stood at 90.2% for the 50s age group, it fell to 75.5% for the early to mid-60s, 52.5% for the mid-to-late 60s, and 32.7% for the early 70s. After passing retirement age, the number of individuals deciding to retire and live off of their pension gradually increased. Meanwhile, estimated health capacity to work stood at 87.8%, 86.2%, and 84.1% for those aged 60–64, 65–69, and 70–74, respectively. Our estimates show that despite the label of "senior," these age groups do not demonstrate significantly deteriorating health – and therefore are capable of working at the same level as they were able to in their 50s.

The above estimates indicate that a maximum increase in the employment rate of 12.4, 33.7, and 51.3 percentage point for those aged 60–64, 65–69, and 70–74, respectively, is possible. The idea that more than 50% of people over the age of 70 had the potential to work was somewhat surprising; we do need to keep in mind – as noted above – that estimates must be interpreted carefully due to the nature of our calculations. It seems more reasonable, however, that about 30% more of those aged 65–69 could potentially join the work force.

It is more difficult to interpret the results for women; they may likely reflect a more diverse array of work styles and the fact that many women have been full-time homemakers. Despite the challenges, we applied the same methodology to women as to men, yielding a 10.5, 22.1, and 28.2 percentage point increase in the employment rate for those aged 60–64, 65–69, and 70–74, respectively. Our results clearly show that the employment rate for women in their mid-to-late 60s could potentially increase by 20%. Though we do not provide details here, we have also ascertained the following results:

1) Men in particular demonstrated the health capacity to work and were given opportunities to make the shift from part- to full-time work.

2) Over the past 30 years, the possibility of continued employment opportunities for older workers – as opposed to retirement – has gradually increased.

Pension System Impedes Senior Employment

The public pension program is a social security system designed to mitigate risk associated with insufficient income for seniors once they retire. Under the current system, however, individuals only need to reach the specified age – which is the same for everyone – in order to claim their benefits; the sole requirement is that they fill out an application. Because of the way the system is set up, most people end up not even considering whether finding employment would be a challenge or not. Significant costs are key to accurately determining each individual's abilities regarding work, and further there is no incentive for the individual to honestly demonstrate their own abilities. Given these circumstances, it may seem reasonable that we would have a system where people retire at a certain specified age – at which employability is generally believed to decline substantially – and that people who have reached this age are encouraged to choose retirement.

However, this kind of decision making engenders significant costs for society as a whole. Though many individuals may be highly employable, a moral hazard arises where the individual believes that it is more beneficial to receive pension benefits rather than continuing to work and acts accordingly. The difference between the potential employment rate and the actual one represents the degree of this moral hazard. The concept that pensions hinder employment may be inconsistent with the traditional understanding of the public pension system. However, under the current circumstances – where we are faced with the urgent issue of forging a larger class of people supporting the pension system amidst Japan's declining population – it is critical to grasp the specifics and extent of how pensions adversely affect employment levels.

It is important to note here that, in Japan, even where individuals have begun receiving pension benefits, it does not necessarily mean that they retire completely; in fact, many continue working part-time for the same employer as they did until they retired. However, as such individuals continue to work, the earnings-tested Working Old Age Pension goes into effect when wages reach a certain level. This means that the individual potentially loses part of their pension. At the same time, they continue to pay pension premiums in accordance with their wage levels (though any such payments are applied to future pension payments made to the individual) as well as income tax. Considering these factors, the sensible choice would be either to retire completely and live off of one's pension, or to continue working but to maintain one's wages at a lower level in order to avoid losing part of one's pension payments.

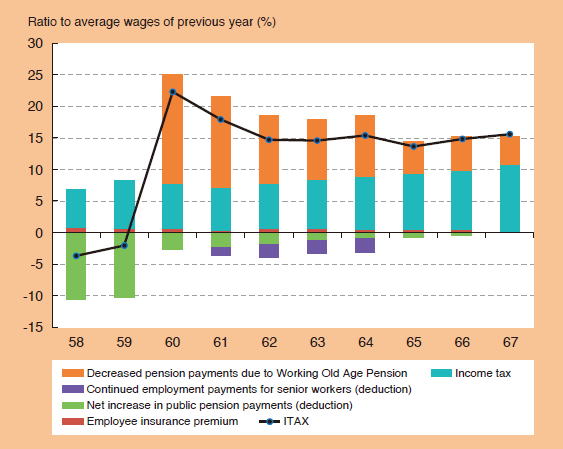

To analyze this situation, we first calculate how much the individual would earn if they continued working at their current age, comparing the amount to how much they would receive if they chose to stop working, and any loss incurred, comparing the percentage of said loss to current wages. This value is then shown together with the implicit tax rate (ITAX) engendered by the pension system. The ITAX is negative for those individuals who have not yet reached the pensionable age. In other words, up until the eligible age for pension claiming, the pension system works to encourage individuals to keep working. However, once individuals reach the pensionable age, the ITAX turns positive due to lower pension payments under the Working Old Age Pension and insurance payments paid. Next, we run a simple equation to determine the impact of the ITAX on older worker employment.

Calculating the Tax Rate of Pension Programs

To calculate the ITAX, it is necessary to first incorporate any pension and insurance payments made to the individual depending on factors such as their birth year, survey date, etc. In addition to these core components of the pension system, various other factors must also be included: the earnings-tested benefits under the Working Old Age Pension; the wage subsidy paid to the older workers whose wages fall below the pre-retirement level after mandatory retirement; individual income tax; and employee insurance premiums.

These ITAX values are calculated at the time of each survey via a longitudinal study on seniors. In Chart 2, we take the example of men born in 1948 (age 57 in 2005), summarizing changes in the ITAX as these individuals aged. As can be seen, when these individuals turned 60, the age at which they could initially claim the earnings-related component of their pension, the ITAX jumped from a negative figure to the 20–24% range, later trending slightly downward to around 15%.

Source: Compiled by the author based on the Longitudinal Study on Seniors (2005-2016), conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

We further examined the changes in the composition of the ITAX. Firstly, we find a substantial decline in the net lifetime pension benefits accrued when working an additional year at age 60. We also note that the Working Old Age Pension pushes up the ITAX for those aged 60–64. Our results indicate that, though somewhat mitigated by the wage subsidy to older workers, the Working Old Age Pension works to significantly impede employment in those aged 60–64.

It should be noted that the pattern of changes in the ITAX as the individual ages differs between men and women and depends on their age. In particular, because the eligible age is being raised to 65, the impact of the Working Old Age Pension on those aged 60–64 is forecast to decline – and to decline more dramatically the younger the generation.

Disincentive Effects of Pensions on Senior Employment

Next, we use regression analysis to determine the extent of the negative impact of ITAX on older worker employment. We also calculate the correlation of ITAX with the rates at which people employed up until one year prior to the survey would stop working as of the current survey year. However, in addition to factors other than ITAX likely to affect the decision to work or to retire, such as total pension to be collected over their lifetime, lifetime wages, state of health, and the need for nursing care in the family, there were also other impeding variables unique to the individual that did not change with time, including level of education and more.

There remain, however, problems with this type of analysis, including the failure to eliminate institutional factors such as the corporate retirement age, as well as the impact of social norms pertaining to seniors. For instance, though the ITAX tends to rise substantially after the age of 60, the retirement age is nevertheless just 60 at many companies. For these reasons, it is uncertain whether declines in employment rates as of age 60 are due to the rising ITAX or to the impact of the retirement age. To clarify this issue and examine the extent of any correlation between the ITAX and the employment rate, we have added dummy variables for each age as explanatory variables to the regression equation.

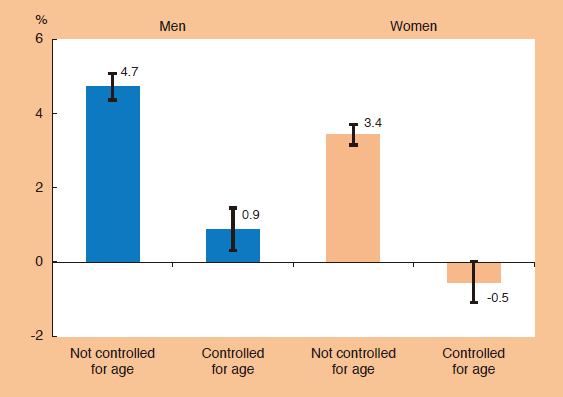

The estimation results by gender are summarized in Chart 3. Here, we estimate the decline in percentage points of the employment rate when the ITAX is raised by 10 percentage points. The respondents used in the analysis ranged in age from 58 – an age where they would soon be eligible to claim pension benefits – to 69. The analysis was limited to individuals who had been employed up to the point in time one year prior to the survey. As this chart indicates, the employment rate is expected to decline by 4.7% with a 10% increase in the ITAX for men and 3.4% for women, without controlling for age factors. After controlling for age factors, employment rates would fall 0.9% for men and rise 0.5% for women. The fact that men were more affected by the ITAX than women may be indicative of the greater diversity of women's lifestyles. We also confirmed that age had a significant impact on retirement decisions.

Error bar indicates confidence interval of 95%.

Source: Compiled by the author based on the Longitudinal Study on Seniors (2005-16) conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

Possible ITAX values, as indicated in Chart 2, range from minus 5% to around 20%, which means that adjustment at around the 10% level remains a realistic possibility. In addition, although the ITAX reflects the pension program, institutional factors such as corporate employment practices including the retirement age as well as social norms are also subject to change. As a result, in assessing the impact of pension reforms on employment, we can take the middle value falling between scenarios where age factors are controlled for and where they are not; that is, we can expect that lowering the ITAX by 10% would reasonably result in a 2% increase in the employment rate

Summary: Policy Implications

The following is a summary of our results as well as policy implications.

Firstly, we estimated how much the older worker employment rate could be potentially bolstered based on health conditions. Based on the observed correlation between health and employment for the 50s age group, we showed that the current employment rate for those aged 60–64 could be boosted by 20–30%. Of course, we need to pay attention to the fact that there will always be some seniors who would be unable to engage in full employment due to health issues. However, if we boost the employment rate among those aged 60–64 years by 20–30%, both insurance premium payments and tax revenues increase substantially – which would greatly ease the current social security systems for seniors. This development would also likely add to growth potential for the economy as a whole. The nation's expanded social security systems, including medical care, have played a critical role in improving health for seniors. As Japan faces the challenges of a rapidly aging population, it would be beneficial to feed back the benefits of these systems to society to boost the sustainability of these systems. System reforms, including of the public pension system and employment programs, are needed to facilitate a greater, yet reasonable, supportive contribution by senior workers, in a manner that corresponds to their state of health.

Second, we analyzed how the pension system might hinder employment. We believe that one major reason why the senior employment rate has not reached its potential is the pension system; to show this, we analyzed the degree to which current systems such as public pensions and taxes had a negative effect on employment by calculating ratios relative to current wage levels. This ITAX rose dramatically when the individual reached the age at which they could take pension payments – a factor that hindered senior employment. Roughly speaking, we can expect that a 10% increase in the ITAX would result in around a 2% increase in the employment rate.

Pension reforms including a further increase in eligible age and a revision of the earnings-tested Working Old Age Pension are urgently needed. These kinds of reform are critical not only for improving pension financing but also for ensuring adequate income for seniors, because they are expected to increase the population of people able to support the social security systems and further to reduce poverty

This article first appeared on the July/August 2019 issue of Japan SPOTLIGHT published by Japan Economic Foundation. Reproduced with permission.

July/August 2019 Japan SPOTLIGHT