Approximately one million elderly people aged 65 and over are on public assistance in Japan, accounting for almost half of the nearly 2.1 million public assistance recipients. The proportion of elderly recipients remained below 30% through the end of the 1980s but has risen gradually thereafter. Today, roughly half of the public assistance is being directed to maintain a minimum standard of living for elderly people.

The percentage of people on public assistance in the total population is referred to as the "public assistance ratio." The public assistance ratio among the elderly had been on a steady decline through the mid-1990s. The development of the public pension system, under which all citizens are covered by at least one program, enhanced income security for elderly people. However, the ratio turned upward subsequently, rising from 1.6% in 1995 to 2.9% in 2015. Although this is partly attributable to the impact of prolonged economic stagnation, poverty that cannot be addressed by income security through the public pension system seems to be occurring among the elderly. The poverty rate for Japanese elderly people living alone is among the highest by international standards. We cannot afford to overlook the reality that poverty is growing among the elderly population.

♦ ♦ ♦

What about the future prospects? Discussions on the outlook for social security benefits are centered on pension, healthcare, and long-term care programs, with little interest shown in the outlook for the public assistance system. However, the public assistance system may have a non-negligible impact on the entire social security system. Let's do some simple calculations to check that point. We consider two cases.

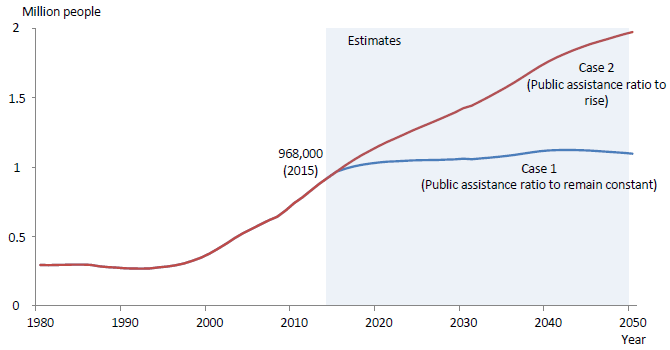

In Case 1, we assume that the public assistance ratio among the elderly population will remain unchanged from the 2015 level (2.9%) to calculate the increase in the number of elderly recipients of public assistance attributable solely to an increase in the elderly population. Meanwhile, in Case 2, we estimate the increase in the number of elderly recipients by assuming that the upward trend in the public assistance ratio over the past 20 years will continue on top of the expected increase in the elderly population.

Calculation results are plotted in Figure below. In Case 1, an increase in the number of elderly recipients of public assistance will be relatively moderate—10% over the period through 2050 compared from some one million at present—as Japan's elderly population is to reach a plateau in due time even though the society is to grow grayer. Meanwhile, in Case 2, the number of elderly recipients will nearly double to reach two million in 2050. Even though the elderly population peaks, the public assistance ratio will rise to around 5%.

Case 2: The public assistance ratio among elderly people aged 65 and over continuing to rise along the extended line of the upward trend between 1995 through 2015

While the Case 1 scenario is too optimistic, the Case 2 scenario is too pessimistic. However, the actual course of events will likely turn out to be closer to the latter.

In this regard, estimates made by Professor Seiichi Inagaki of the International University of Health and Welfare provide good reference. His estimates showed that the percentage of those with income below the public assistance eligibility threshold would increase from 12% in 2009 to about 25% in 2060 for women and from 6% to about 14% for men, taking the current public pension system as given and assuming that there will be little change in the make-up of families. The scenario presented by Professor Inagaki's estimates is closer to the Case 2 scenario.

♦ ♦ ♦

The Japanese society will be facing a serious problem, i.e., growing poverty among the elderly, down the road. As a general tendency, those who are in non-permanent employment and/or working short hours are not making sufficient personal contributions to the public pension system, and hence, the expected result is a significant increase in the number of people left with no or an extremely low amount of pension benefits in the coming years. The problem of growing poverty has not yet surfaced because many of those people are maintaining their livelihoods by relying on the income of other family members, such as parents' pension income. However, their aging parents will pass away at some point in the future. This means that a significant number of people will have no family to rely on in their old age, while being entitled to pension benefits, if any, that are not enough to sustain their livelihoods. If so, the problem of growing poverty exists in macroeconomic terms.

Is Japan's current social security system prepared for growing poverty among the elderly? The implicit consensus within the government seems to be that support for people with no or an extremely low amount of pension benefits should be dealt with by the public assistance system, rather than the public pension system. Indeed, pension system reform ideas designed to address the problem of elderly poverty—e.g., the introduction of a guaranteed minimum pension for all—have been turned down for reasons such as the need to raise the consumption tax rate.

However, elderly poverty as a full-blown problem is not part of the design of the public assistance system as it stands today. The system is fully financed by public funds and thus subject to yearly budget negotiations, meaning that its implementation is not necessarily guaranteed. People's refusal to accept higher taxes—whether in the form of the planned consumption tax rate hike or else—will pass on greater burdens to future generations, or increase pressure to cut back on pension benefits.

The public assistance system, a mechanism designed to guarantee a minimum standard of living for all, also aims to "promote self-support" (Article 1 of the Public Assistance Act). Given the presence of other key social security systems, such as the public pension and healthcare insurance systems, the public assistance system can be defined as a mechanism to provide an emergency shelter for those who have become unable to sustain themselves. The implicit assumption is that recipients of public assistance would be limited in number. It is precisely because of this that the government has been able to tolerate the financial vulnerability of the system. Today, however, the government finds it increasingly difficult to condone the situation.

It is also unreasonable to define the public assistance system as a mechanism for supporting those elderly people who are having difficulty sustaining themselves and in need of long-term assistance. Furthermore, the problem of moral hazard, which is inevitable in any public assistance system, would become too serious to ignore socially, as the amount involved increases in tandem with an increase in the number of recipients.

I believe that the measures for addressing elderly poverty should be built around the public pension system, not the public assistance system. Enhancement of old age income security should be realized by means of a social insurance mechanism, under which all of the participants in the program support one another. That way, it would be easier to obtain public understanding. The public assistance system should be defined as an emergency mechanism for the elderly, as well as for the working population.

A key element here is an automatic benefit adjustment mechanism called a "macroeconomic slide" introduced in the 2004 public pension system reform. The mechanism has substantially increased the financial sustainability of the public pension system by enabling adjustments to the level of benefits paid to pensioners according to changes in that of burdens on the current working generation. However, we must not forget that this would be possible only at the cost of accepting cutbacks in pension benefits.

When the macroeconomic slide system comes into play, the amount of pension benefits receivable determined upon reaching the pensionable age is bound to fall, which would translate into a significant decrease in income for those eligible only for benefits under the Old-Age Basic Pension program and those entitled to receive earnings-related benefits but only in small amounts. Ironically, the public pension system may operate to provide lesser income security to those having difficulty securing income for themselves. Meanwhile, the public assistance system, a mechanism likely to be used as a substitute, is not robust in the first place and will likely become more fragile in the coming years.

♦ ♦ ♦

What should we do? We should seek to alleviate as much as possible the risk of falling into poverty in old age and strengthen the income security function of the public pension system.

First, it is necessary to expand the coverage of employees' health insurance programs to include non-permanent part-time workers to reduce the risk of being left outside the safety net of the public pension system. We should seek to create a social insurance mechanism applicable to all or as many people as possible, under which people help each other by making contributions according to their respective income levels, instead of splitting them into those supporting and those being supported. That way, it would be easier to get backing from the public.

Second, raising the pensionable age will be effective, too. Indeed, this will have a neutral impact on the financial status of public pension programs under the macroeconomic slide system. However, it would have a significant impact in terms of addressing the problem of elderly poverty, if raising the pensionable age could create room to increase the level of pension benefits even by the slightest amount. Setting a slightly higher age threshold for eligibility for guaranteed income while raising the level of benefits for those entitled to a low amount of pension benefits would be an option worthwhile considering.

Lastly, I would like to point out that it would not necessarily require a complete overhaul of the social security system. The amount of public assistance provided in 2015 was less than four trillion yen, compared to some 55 trillion yen paid in public pension benefits. Probably, only about half of the amount paid in public assistance was for elderly people. Furthermore, public assistance recipients are still limited in number. If so, we should be able to solve many of the existing problems by partially reforming the current public pension system.

The public assistance system is the last resort measure the government would take to guarantee a minimum standard of living for all. In order to enable the system to work properly when the need arises, we should avoid subjecting it to unnecessary burdens. We must act quickly to reform the public pension system before the problem of elderly poverty surfaces and becomes out of control.

* Translated by RIETI.

March 26, 2018 Nihon Keizai Shimbun