Japan's unemployment rate is hovering below 3.5%, the lowest level since 1997, while the ratio of job offers to job seekers remains above 1.2, the highest since 1992. Against this backdrop, service industries are suffering from a chronic shortage of workers, which has been ongoing for more than four years. Meanwhile, Japan's real gross domestic product (GDP) has been almost flat since the fourth quarter of 2013 when the job offers to seekers ratio exceeded one.

This is partly due to the negative impact of the consumption tax rate hike in April 2014, but the period of zero growth also includes the period preceding the tax hike, during which demand was pushed upward by last-minute purchasing. Given a certain level of potential growth rate, it is impossible for zero growth to continue throughout the period of full employment. In other words, the current situation is not about a cyclical downturn but weak growth.

Concerns have been voiced over wage rigidities or the failure of wage levels to rise despite tightening labor supply. Factors behind this include an increase in the proportion of "non-regular workers," which collectively refer to workers other than those in permanent full-time employment, and the weak bargaining power of workers, but the biggest root cause lies in weak growth in productivity. It is thus hoped that service industries, which constitute more than 70% of the Japanese economy, will improve productivity

♦ ♦ ♦

The primary source of value added for today's manufacturers is at the two ends of the so-called "smile curve" of the value chain, namely, the designing and development of products at the upstream segment and marketing and after-sale services in the downstream segment. Meanwhile, some studies on global value-added chains have shown that, when measured in terms of value added, the share of services as inputs in manufacturing industrial goods for export is significant and expanding particularly in advanced economies with a competitive advantage in skill-intensive services. Today, services are an important contributor in supporting the international competitiveness of manufacturing industries.

It is often said that productivity in Japanese service industries is low. Indeed, the pace of productivity growth of the service sector is slower than that of the manufacturing sector. But such is the case not only in Japan but also in other advanced economies. Furthermore, a closer look reveals that both the service and manufacturing sectors have industries with high productivity growth and those with low productivity growth. In the first place, it is technically difficult to measure improvement in the quality of services.

It is also pointed out that Japanese service industries compare poorly to their U.S. counterparts in the level of productivity. In order to enable international comparisons in the level of productivity, it is necessary to convert the prices of services into a common currency, using the ratio of the prices in national currencies of the same service in different countries, i.e., purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rates. However, unlike industrial products, many of which are traded internationally, it is often difficult to find the same service in multiple countries.

For instance, we can compare transportation services in different countries simply in terms of the cost per unit distance traveled. But the quality of services—e.g., frequency and reliability of service—is not the same across countries. A survey conducted by the Japan Productivity Center found that the quality of many types of services in Japan is considered to be 5% to 10% higher than that in the United States, indicating the degree to which the productivity of such types of services is underestimated.

Accurate measurement of productivity is not easy, which makes it all the more important as a theme of academic research. In terms of actual policymaking, starting from identifying where there is room for improving productivity is a realistic approach.

♦ ♦ ♦

An increase in the productivity of an industry is brought about by two factors: 1) increased productivity of individual firms (within effects) and 2) the entries of highly efficient firms and the exits or shrinking of inefficient firms (reallocation effects). Regarding the second factor, substantial productivity gaps exist even among firms in the same industry and such is particularly the case in service industries. In other words, while there are many inefficient firms, there also exist many excellent ones. Thus, there is much room for improving productivity by means of intra-industry reallocation.

Easing market entry regulations such as monopolistic occupational licensing systems and reviewing government policies that provide excessive protection to small and medium enterprises and sole proprietors work to enhance reallocation effects. For instance, some empirical studies overseas point to a significant degree of substitutability between physicians and nurses as well as between dentists and dental hygienists, arguing that the scope of tasks undertaken by nurses and dental hygienists should be expanded and that the existing occupational licensing system should be converted to a certification system.

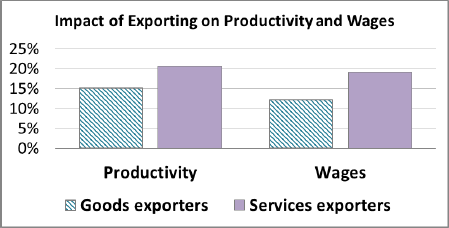

Generally speaking, both the productivity and wage levels of exporters (international firms) are higher than those confined to domestic operations (non-internationalized firms) (see the top chart in the figure below). Therefore, international initiatives for the liberalization and facilitation of trade in services such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement have the same effect through enabling efficient firms to expand their market shares.

Many types of services are characterized by the simultaneity of production and consumption, a feature not observed in manufacturing industries, and hence, the productivity of a specific service provider is very much determined by its location. Accordingly, geographic reallocation—i.e., migration of people and firms from one place to another—also affects the productivity of a country as a whole. In this regard, government policies for land use and city planning and those for the labor market will help improve productivity in service industries through the economies of agglomeration, when they are designed to facilitate the selection of and concentration on highly productive areas in spatial terms.

Meanwhile, within effects are a function of various factors, which include service innovation, higher capacity utilization achieved through the use of information technology (IT), multi-store operations that take advantage of economies of scale, and improvement in the quality of management. Along with improvement in the quality of human capital, innovation constitutes the biggest driving force of productivity. Service firms' investment in research and development for hard innovation is relatively small. But attention needs to be focused on their soft innovation such as the development of high quality human resources, organizational and operational reforms, and brand building.

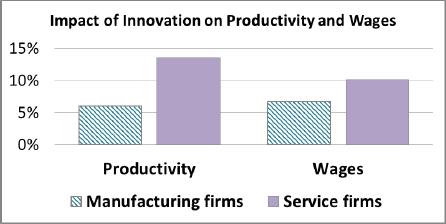

Also, it should be noted that productivity and wage gaps between firms with innovation and those without are far greater in service industries than in manufacturing industries (see the bottom chart in the figure).

New technologies such as big data and artificial intelligence (AI) have the potential to dramatically improve productivity in service industries. In terms of policy options to promote service innovation, effective measures include ensuring proper legal protection for customer data and know-how not covered by patents and offering support measures for education and training of employees and other investment in intangible assets.

In service industries that do not carry any inventory, productivity is determined by the extent to which capacity utilization can be improved by leveling the demand. A rapid rise in inbound tourists to Japan has pushed up occupancy rates in hotels and other accommodations, contributing to productivity improvement in the lodging industry. In addition to an increase in the total number of overnight guests, there are significant demand-leveling effects resulting from differences in the pattern of hotel stays between Japanese and foreign tourists such as the length and timing of stays. And there is significant room to use IT as a means to improve capacity utilization.

Indeed, many empirical studies have shown that effective use of IT has led, via increased capacity utilization, to remarkable productivity improvement in the logistics and passenger transportation industries. Sharing services, which are rapidly growing in some overseas markets, have similar traits. Analytical findings from a comparison between Uber's ride-on-demand services and conventional taxi services in the United States have shown that the capacity utilization rate is at least 30 percentage points higher for Uber drivers than for taxi drivers. Factors behind this include Uber's efficient driver-passenger matching based on mobile Internet technology and flexible labor supply adjustments depending on the time of day as well as inefficient regulations on conventional taxi services.

♦ ♦ ♦

Productivity in service industries is closely linked with various economic and social regulations and systems. In this regard, not only policy measures targeted at specific industries but also those designed to reinforce infrastructure for growth, such as creating a pro-innovation business environment and enhancing the human capital of workers, are quite important. Other useful measures include those with reallocation effects such as removing regulatory barriers inhibiting intensive land use in metropolitan areas and a shift to compact cities, and reforming the labor market system in a way to facilitate inter-industry and inter-regional labor mobility.

However, such measures may involve trade-offs in other social values such as promoting the balanced development of regions across the country and ensuring job stability.

If this is the case, adverse effects accompanying the pro-productivity reform measures should be dealt with by a separate set of supplementary measures designed to alleviate them. For instance, if there is a negative impact on job stability, supplementary measures should include increasing education and job training opportunities and enhancing the social safety net. In order to promote women's labor force participation and address the low fertility problem in big cities, it is important to make a focused effort to enhance commuting infrastructure and increase the capacity of childcare service facilities in densely populated areas along with facilitating the geographical mobility of people. There is much room to improve productivity in service industries, and there are many things that can be done by means of government policy.

* Translated by RIETI.

April 26, 2016 Nihon Keizai Shimbun