Competition laws regulate mergers and other forms of business consolidation that develop, maintain, and strengthen market power (the power to influence market factors, including price, quality, and innovation). In the European Union (EU) and the United States, the enforcement of merger regulations by the competition authorities has quickly increased since 2021. The situation is the same in the United Kingdom, which has left the EU. This is partly a reaction to criticism that authorities have avoided applying competition law to companies despite the need for its enforcement.

First, there has been growing criticism that there is an increasing trend in the United States of mergers that strengthen the market power of the merged firms. Next, there have been reports of many prominent cases of the competition authorities apparently ignoring continued efforts by “Big Tech” companies (of which GAFA, a group of very powerful U.S. technology companies, are the main examples) to strengthen market power through mergers and acquisitions.

Examples include cases of “killer acquisitions,” which refers to a dominant firm’s acquisition of an emerging competitor to preempt a future threat to their business or market share; and cases of market foreclosure, which refers to efforts to exclude competitors with growth potential from the market by depriving them of business opportunities. Recently, there is increasing awareness of various types of potentially harmful mergers that the authorities had, until recently, disregarded.

The current strengthening of enforcement by the competition authorities reflects both the tightening of their regulatory stances in general and their response to new types of potentially harmful mergers. In a development emblematic of this trend, in July 2023, the U.S. competition authorities announced draft merger guidelines.

The assessment of market power development is conducted on the basis of sophisticated economic analysis as to how the situation may be affected in the future. At the same time, as enforcement is related to legal standards that are subject to judicial reviews, competition authorities of various countries have published guidelines in order to enhance regulatory transparency. The U.S. guidelines have always had a significant impact on other countries’ regulation of mergers.

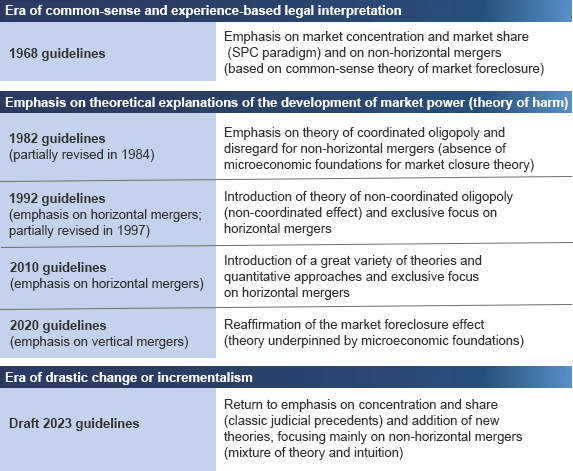

The draft guidelines published at this time are considered to be revolutionary and are expected to dramatically change the regulatory trend. Let us look back at the history of the U.S. merger guidelines (see the table below).

◆◆◆

The first guidelines were published in 1968. Those guidelines were faithful to the argument of the “structure–conduct–performance (SCP) paradigm,” which was at that time the mainstream idea under industrial organization theory.

The 1968 guidelines adopted the principle that regulating activities that could significantly increase market concentration was necessary, based on empirical evidence that in a highly concentrated market structure, competitive behavior, and by extension the benefits of the market, may be undermined. They also placed the focus on empirical evidence that not only horizontal mergers, which integrate companies in a competitive relationship with each other, but also vertical and mixed mergers, could cause market foreclosure, create entry barriers, and harm potential competition, thereby presenting market power issues. This approach was based on judicial precedents where the Supreme Court determined the illegality of mergers that further increase concentration in an already highly concentrated market.

However, the guidelines issued in 1982 changed the situation dramatically. On the whole, the 1982 guidelines were based on microeconomic theories. Rather than paying attention exclusively to an increase in market concentration, they focused on explaining (based on economic theories) how market power is developed. This shift in the regulatory approach was regarded as a revolutionary change engineered by the Chicago school of economists, who adopted an accommodative stance toward monopoly. Under the theoretical framework at that time, emphasis was placed on which sorts of cases could cause market concentration and lead to oligopolistic coordination.

The 1992 guidelines, affected by the advance of game theory, emphasized a theoretical framework that explains how market power can be created without coordination as a result of the reduced competitive pressure resulting from a merger in an oligopolistic market (non-coordinated oligopoly).

The 2010 guidelines appeared to be something like a catalogue of analysis tools developed by the U.S. competition authorities. They contained various theoretical explanations as to why horizontal mergers may harm competition and described quantitative approaches used by the competition authorities. In particular, they emphasized the approach of quantifying the price-increasing effect of mergers between competing firms in non-coordinated markets. The advance of those theories and quantitative approaches led to the development of the methodology for assessing the efficiency of mergers in concrete terms, that is, in terms of a competition-promoting effect.

On the other hand, non-horizontal mergers were disregarded for many years. However, as more and more empirical studies showed that such mergers generate negative effects, the guidelines issued in 2020 focused exclusively on horizontal mergers.

From 1982 onwards, the development of successive guidelines represented the adoption of technical incrementalism under bipartisanship, but the draft 2023 guidelines can be viewed as a departure from the existing analysis framework in the following respects.

◆◆◆

First, the guidelines issued after 1982 but before 2023 explained regulatory approaches in terms of economic theory, but the 2023 draft guidelines relegate explanations based on economic theory to the appendix section and that the analytical guidelines are essentially legalistic text that contains examples of precedent citations. Second, the draft guidelines attach importance to the empirical norm adopted in the 1968 guidelines—that mergers that increase market concentration are anti-competitive—and set the threshold for concentration at a very low level. The draft guidelines also frequently use wording that could cause market concentration to be confused with market power.

Furthermore, regarding the types of mergers that have recently become the focus of attention, the draft guidelines often refer to theories used in precedent cases and use wording that appears to attach importance to ideas based on simplistic reasoning rather than established economic theory. It seems that the United States has in a sense returned to the “Era of common-sense and experience-based legal interpretation” which existed before 1982 due to the presence of an advocate of the New Brandeis School of antitrust law among the senior ranks of the competition authorities.

Even so, the draft guidelines, including the main body of text, also contain updates based on economic theory, and parts of the guidelines that appear to provide simple explanations may also be interpreted to be founded on economic theory.

Why do the draft guidelines use wording suggestive of a shift in emphasis back toward simplistic reasoning? One reason is that this approach is a response to the biases indicated by the courts’ handling of recent cases and the recent status of enforcement of competition law. In cases against mergers, some lower courts tend to require that the competition authorities prove that there is a high probability that competition will be greatly harmed. Therefore, the authorities tend to concentrate on showing quantitative evidence that mergers will lead to higher prices, rather than providing qualitative explanations. As a result, the focus tends to be on the very short-term impact of mergers in narrow markets, a situation that in turn gives rise to the tendency to neglect theoretical explanations that qualitatively prove competitive harm (analyses of monopolistic coordination, market foreclosure, and potential competition).

In the EU, in July 2023, the European Court of Justice (the EU equivalent of a supreme court) issued a ruling in a case against a merger. While the competition authorities determined the merger to be illegal based on evidence, including the results of quantitative analysis, a lower court voided the authorities’ determination from a unique economic perspective—that court, like some U.S. courts, presumed that the merger would bring efficiency and required the authorities to prove a harmful competitive impact that outweighs the presumed efficiency improvement. However, the European Court of Justice pointed out in detail the erroneous understanding on the part of the lower court and annulled its ruling. In this case, it may be said that the bias-correction function worked within the judicial system.

To realize an appropriate level of merger regulation, it is essential for the competition authorities not only to increase the sophistication of their economic analysis, including theoretical and empirical analysis, but also to accurately explain their analytical approaches to the judicial branch and obtain its understanding.

In Japan, a judicial review of merger regulation has not been conducted for many years. However, if a judicial review is to be conducted, courts are likely to require the development of a framework for resolving disputes between the Fair Trade Commission and companies involved in mergers. In addition to updating analysis tools and conducting an ex-post review as to whether the current level of regulation is appropriate, it is desirable to develop a framework that can be appropriately understood by the judicial branch.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

September 20, 2023 Nihon Keizai Shimbun