1. Introduction

For the past year or two, not a single day has gone by that we have not discussed the topic of inflation around the world. Japan is no exception. Inflation is at its highest rate in 40 years, and the yen is losing its value significantly. In February 2020, the yen-dollar rate was around ¥110 to the dollar, but the yen began to fall in early 2021. In October 2022, the yen dropped to 147 yen, its lowest level since 1998. The last two years have seen a staggering 25% drop (Note 1).

Not surprisingly, much is discussed about the economic impact of exchange rate fluctuations. Traditionally, it has been somewhat simplistically argued that a weaker yen is good for the Japanese economy because it lowers the price of its products in the global market and increases sales and profits for exporting companies. Similarly, under this view, a stronger yen is bad for the economy.

This time, however, we often hear the argument that a weaker yen is not necessarily good for the Japanese economy. Japanese companies, especially large multinational corporations, often produce parts and unfinished products at their overseas production bases in China and East Asia, export them to Japan, and then export the final products to markets in Europe, the United States, and other countries. In this kind of industrial and trade structure, a weak yen could have a negative impact on the real economy by raising production costs and worsening corporate profits. It is also argued that since Japan relies on imports for most of its food and energy, a weak yen is said to reduce corporate and personal consumption, cooling down the overall economy.

However, the impact of exchange rate movements on the economy cannot be easily summarized. It varies from industry to industry and from company to company and depends on whether one is considering the impact on consumers, workers, or investors.

I would like to bring up two points of concern regarding the recent debate in Japan on exchange rate fluctuations. One is the argument that Japan's recent tendency to run trade deficits is a sign of a decline in its national strength since its wealth is flowing out of Japan and into foreign countries. Theoretically, when considering exchange rates, wealth distribution, and economic fluctuations, it is the current account balance that matters and represents money flowing in and out of a country in aggregate, not the trade balance (Note 2).

The trade balance and the current account balance should not be regarded as equivalent to each other although some observers sometimes mix them up. Trade balances often get politicized as we have seen between the United States and Japan in the 1980s and 1990s and between the U.S. and China for the last few decades. A misunderstanding of trade and current account balances can lead unnecessarily to political division and confrontation.

Second, when discussing the impact of exchange rate fluctuations, very little is said about the so-called “valuation effect” of exchange rate fluctuations on Japan's external wealth. Trends in the current account balance and exchange rate fluctuations affect Japan's financial assets and liabilities to foreign countries, and therefore, the accumulation of Japan's external wealth. However, this mechanism has not been discussed much in the Japanese media. First of all, the discussion overly concentrates on the relationship between the exchange rate and the trade balance, and there is little discussion of Japan's external wealth accumulation.

This paper aims to explain the valuation effects of exchange rate fluctuations, especially those of the Japanese yen, while describing international macroeconomic accounting, which is often considered labyrinthine, as clearly as possible. To this end, we would like to answer the following three questions. (1) Why is it necessary to focus on the current account balance rather than the trade balance? (2) What does Japan's balance sheet look like? and (3) What effect do yen exchange rate fluctuations have on Japan's external wealth?

2. It is NOT the Trade Balance, But the Current Account Balance That Matters

According to the “trade deficit is bad” argument, which we often hear these days, a trade deficit means that Japan imports more than it exports, which means that more money flows out of Japan than it receives from foreign countries. They expand their argument to claim that Japan's trade deficit drains the country's wealth out of the country. From the perspective of international macroeconomics, this is a fallacy. This type of argument used to be common in the U.S. in the 1980s when the U.S. and Japan had economic frictions. Ironically, a similar argument is now being made in Japan.

It is the current account balance, which traces the overall flow of money, that has economic significance, not the trade balance.

The current account consists of the trade balance, the primary income balance, and the secondary income balance (Note 3).

Current account = trade balance + primary income balance + secondary income balance (1)

The trade balance captures payments (imports) and receipts (exports) from transactions in goods and services. The primary income balance (also called net income transfer) includes interest and dividend payments coming from abroad and earnings of companies and workers operating in foreign countries. For example, if a Japanese person owns shares of Apple Inc. in the U.S., he/she receives dividends from Apple Inc. in the U.S., which is counted as an income transfer (receipt) to Japan.

Some economic commentators explain the trade balance and the current account balance as if they were identical. However, in a globalized world, there are many opportunities for migrant workers to send money home to their families in their home countries or to receive dividends and interest from companies located abroad. In other words, the more globalized the world becomes, the greater the share of net income transfers and the more important role they play.

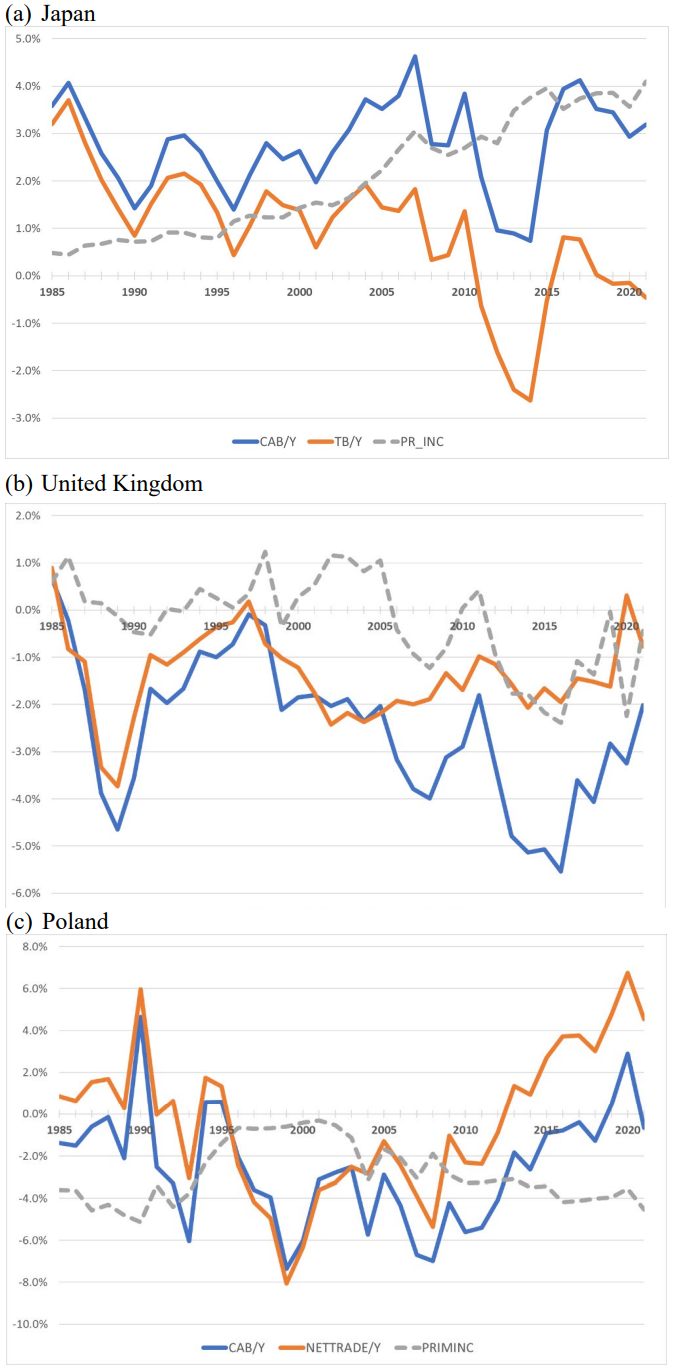

Figure 1 shows the current account balance, trade balance, and primary income balance as a percentage of nominal GDP for Japan, Poland, and the United Kingdom.

In Figure 1, the difference between the two solid lines, the current account balance (blue) and the trade balance (red), is generally small until the early 2000s (though the difference started diverging as early as the early 1990s for Japan). Since then, however, the distances between the two lines tend to increase. In the case of Japan, the trade balance has been 2-3 percentage points lower than the current account balance since the early 2000s. Its trade balance turned negative in 2011 for the first time since the early 1980s due to increased import demand for national resources and materials needed for reconstruction following the Great East Japan Earthquake. The trade balance turned positive again in 2016 and 2017, but turned negative again in 2019. However, Japan's current account balance has never been negative during the sample period. This is because dividends and interest incomes from foreign investments by Japanese citizens as well as companies, and corporate profits, have been returned to the Japanese economy (primary income balance is in surplus).

The current account balance of the UK is the exact opposite of that of Japan. Both the trade and current account balances have been in deficit throughout the sample period, but since 2006, the current account deficit has exceeded that of the trade balance. The difference between the two is due to the deficit in income transfers, which reflects the large amount of profits and dividend payments from companies located in the UK to foreign countries, as well as the remittances of migrant workers in the UK back to their home countries.

Although Poland is different from the UK in terms of the level of development (the UK's GDP per capita is about 2.5 times that of Poland), a similar explanation can be given to characterize the current account, trade balance, and income transfers of Poland. The gap between the current account balance and the trade balance, with the latter higher than the former, has widened since Poland joined the EU in 2004. The country’s primary income balance has been in deficit. It is a typical case that shows once a country becomes more open to foreign investment, its gap between the current account and trade balance gets larger.

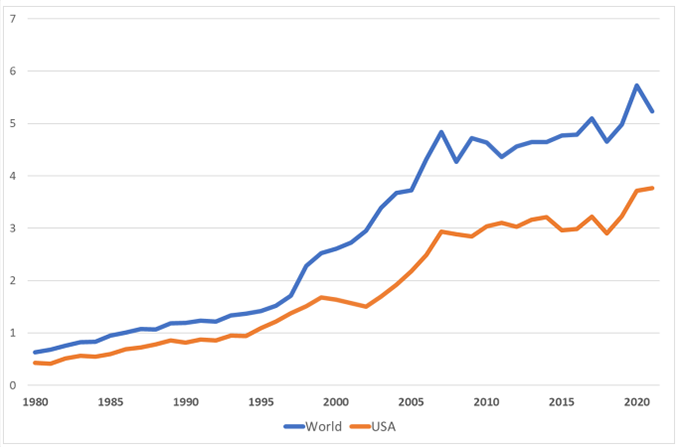

Figure 2 shows the sum of external assets and liabilities worldwide divided by world GDP, and can be used as an indicator of the degree of financial globalization. The figure illustrates that financial globalization has deepened since around 2000. The orange line represents the extent of U.S. financial globalization, but the gap between the two lines has been widening, indicating that the deepening of financial globalization is not solely due to the U.S.

As globalization proceeds, the role of cross-border income transfers increases, which can make the trade balance and the current account balance diverge. Hence, the correlation between the current account balance and the trade balance should become lower. In fact, especially in advanced economies, the correlation coefficient between current account balances and trade balances averaged about 90% before 2000, but has since declined to about 70-80%.

3. Current Account Balances and the Net International Investment Position (NIIP)

Again, the current account balance is the sum of the trade balance and income transfers (i.e., equation (1) with the secondary income balance omitted).

If we consider exports as money flowing into the home country (i.e., residents) and imports as money flowing out to foreigners (i.e., non-residents), the sum of exports and income receipts equals the total amount of money flowing in, and the sum of imports and income payments equals the total amount of money flowing out. In other words, the current account balance is a net flow of money, or more formally, capital (equation (2)).

Current account=Capital inflows-capital outflows=net capital inflows (2)

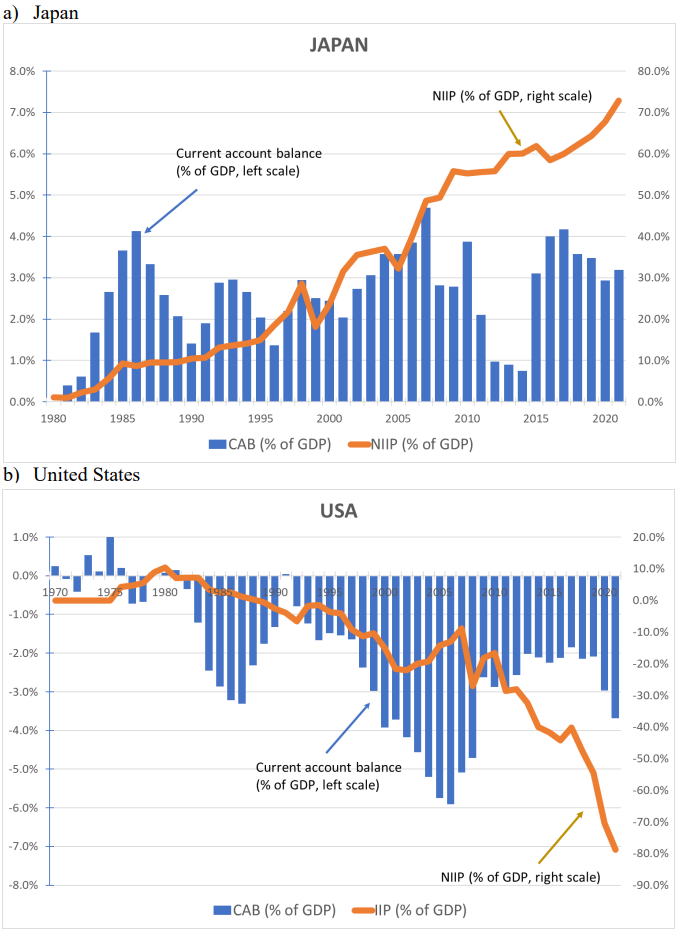

Japan has been running current account surpluses persistently since 1981. This means that the inflow of funds from abroad (capital inflows) has exceeded the outflow of funds from Japan (capital outflows). With external assets constantly exceeding its external liabilities, Japan has become the world's largest creditor nation. As of the end of 2021, Japan had an external surplus of $3.6 trillion, or about 75% of its GDP (about ¥411 trillion at the exchange rate of 114 yen to the dollar as of the end of 2021 (Figures 3(a) and 4(a)). On the other hand, the U.S. is the world's largest net foreign debtor (Note 4). Its debt amounts to about 70-80% of the U.S. GDP, or $17-20 trillion (Figures 3(b) and 4(b)).

Current account surplus countries, like Japan, hold surplus capital in the form of financial assets such as U.S. Treasury bonds, which in effect means that they are lending capital in the form of investments (for example, holding U.S. Treasury bonds as assets is the same as lending money to the U.S. government). Current account deficit countries, like the U.S. and the UK, have to borrow from the rest of the world because they hold more payments than they receive. In other words, current account surplus countries are net lenders and current account deficit countries are net borrowers.

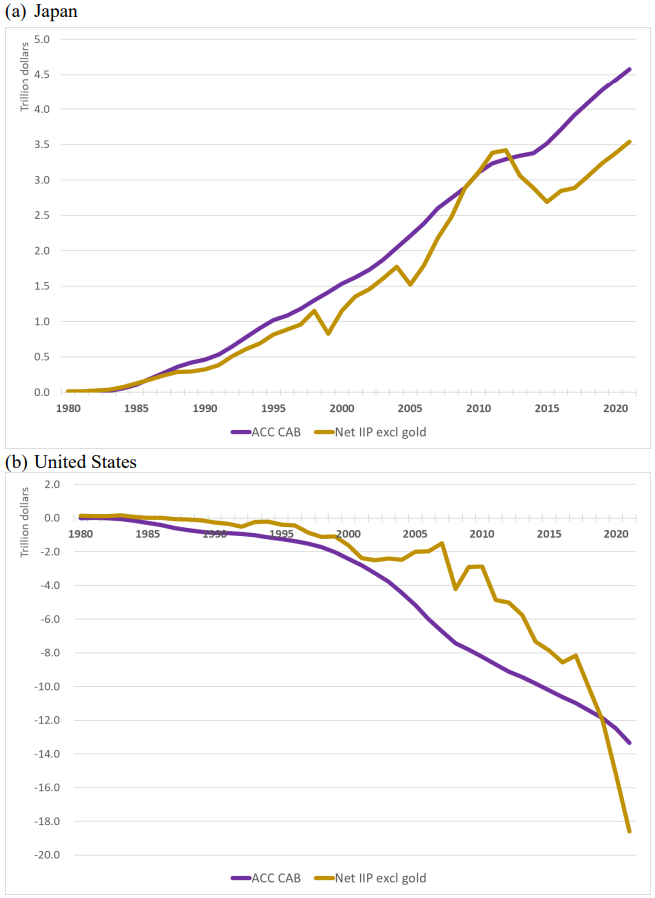

Figure 4 illustrates cumulative current accounts and NIIP for Japan and the U.S. (Note 5) Figures 3 and 4 make it clear that Japan has consistently increased its net foreign assets by running current account surpluses whereas the U.S. has increased its net foreign debt by running a current account deficit.

Note: Cumulative current accounts mean current account balances accumulated since 1980 for each year.

4. Exchange Rate Fluctuations and Japan's External Balance Sheets

A country's balance sheet is a compilation of the “external assets” and “external liabilities” of the citizens belonging to that economy. For example, if a Japanese citizen holds U.S. government bonds issued by the U.S. government, he or she has the right to insist that the U.S. government convert the bonds into cash, and the U.S. government is obligated to provide the bondholder with cash. In this case, the U.S. government bond would appear on the asset side of the Japanese balance sheet and on the liability side of the U.S. balance sheet.

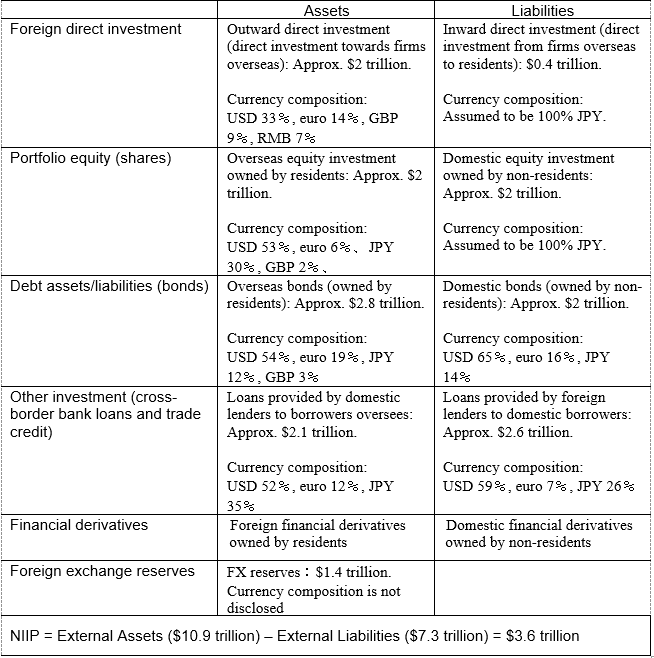

Japan's balance sheet includes all foreign assets and liabilities owned by Japan, including Microsoft stock owned by the Japanese (an asset for Japan), bonds issued by Toyota to raise funds and owned by non-residents (a liability), Australian dollars owned by the Japanese (an asset), loans from U.S. banks to Honda in Japan (a liability), Japanese government bonds held by non-residents (liabilities), shares of foreign companies owned by SoftBank (assets), and foreign exchange reserves such as Chinese yuan, U.S. dollars, and euros owned by the Bank of Japan (assets). The balance sheet is disaggregated into categories such as foreign direct investment (FDI), equity investment (stocks and bonds), financial derivatives, other investment (bank loans, trade credit, etc.), and foreign exchange reserve assets (foreign currency denominated assets held by the central bank) as shown in Table 1.

We saw in Figure 4 that the NIIP can be explained by the accumulated current account balance. The figure also shows that although the accumulated current account balance represents the trend in the balance of net external assets, the accumulated current account balance does not necessarily explain the balance of net external assets completely, as can be seen in the gap between the two lines. In fact, the change in net external assets balance is composed of the following three components.

Change in NIIP = current account + exchange rate fluctuations + movements in the price of assets (3)

The effect of exchange rate fluctuations on foreign net assets is called the “valuation effect.” How exchange rate movements affect foreign wealth can be understood by considering a country as an investor holding a portfolio similar to the one shown in Table 1. For example, it is relevant whether the country of concern holds more direct investment assets than equity assets, how much it owes to foreign investors in terms of bonds or bank loans, and so on. Importantly, the currency composition of each asset class or liability category also affects the valuation effect.

Japan holds much of its external assets in foreign currencies. It also holds a large amount of liabilities denominated in foreign currencies, such as the U.S. dollar and the euro, but the amount is relatively small in relation to its overall portfolio. In other words, Japan has a long position in foreign currencies. This characterization also applies to many advanced economies. In economies that take long positions in foreign currencies, when the value of the home currency declines, the foreign currency assets held by the economy increase in value, and the net foreign assets balance tends to improve.

Source: Compiled by the author using the data from the Bank of Japan, the Ministry of Finance, and others. Refer to footnote 7 for more details.

The U.S. is a special case. Since most of its external liabilities are denominated in its own currency, i.e., the U.S. dollar, a depreciation of the dollar has no effect on the value of its external liabilities in its own currency, but it does increase the value of its external assets in terms of dollars. Thus, depreciation of the dollar has the effect of improving the U.S. external net worth (Tille, 2003). In Figure 4(b), the U.S. NIIP appears to be less negative than the accumulated current account balance from 2000 to about 2019. This is due to the trend of persistent depreciation of the dollar during that period.

In contrast, many developing countries hold large amounts of external debt, about 60% of which is denominated in dollars. Hence, if the U.S. Federal Reserve raises policy rates to reduce inflation, as it has been doing as of this writing, it will cause the dollar to appreciate and the local currency to depreciate, which may increase the debt burden in the local currency for developing countries. Thus, for these countries, a weaker local currency could worsen their net external assets position.

The tendency of developing countries to rely on foreign currency-denominated debt (especially bonds) is called the “Original Sin” in international macroeconomics (Eichengreen et al., 2002). Foreign currency-denominated borrowing can potentially lead to a “currency mismatch” especially for developing countries (i.e., the borrower's currency differs from the lender's currency, and the borrower has difficulty repaying the debt due to a shortage of hard currency). Many developing countries are viewed as risky due to their macroeconomic instability and fragile financial systems, making it difficult for them to raise funds in their own currencies in overseas markets. According to data from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the share of foreign currency-denominated debt in the international bond market hovers around 90%, with the share of dollar-denominated debt hovering around 60% for the last 30 years, and the share of euro-denominated debt around 15 to 20% (Ito and Rodriguez, 2020). The large amount of foreign-currency-denominated debt means that these currencies are more vulnerable to policy changes and other external shocks in developed countries, especially the United States. This vulnerability to spillovers becomes apparent when the home currency depreciates, which in turn causes a further deterioration in the NIIP of developing countries and the values of their currencies. This vicious cycle can eventually lead to a financial calamity.

Fortunately, Japan does not bear the “original sin.” This is because its external assets exceed its external liabilities and its external liabilities denominated in foreign currencies are relatively small.

Let us examine again the impact of a yen depreciation on Japan’s net external assets, using Japan’s portfolio shown in Table 1.

First, Japan’s external assets are $10.9 trillion (1,242 trillion yen) at the end of 2021, while its external liabilities are $7.3 trillion (832 trillion yen), thus its net external assets are the difference, $3.6 trillion (411 trillion yen).

The composition of Japan's portfolio is such that it has about $2 trillion in outward FDI, which is much larger than its FDI liabilities (inward FDI, about $0.4 trillion). Assuming that outward FDI is denominated in the currency of the country in which it is invested, as Lane and Shambaugh (2010) have done, about 33% is in dollars. Similarly, we assume that inward FDI is denominated in the Japanese yen.

Equity investment, both assets and liabilities, is estimated to be about $2 trillion, and about half (53%) of outward equity investment is dollar-denominated. Since most purchases of Japanese equities by foreign residents are assumed to be yen-denominated, almost all inward equity investment can be assumed to be yen-denominated (as was the case with inward FDI).

According to the BIS, 54% of outward bond investments are denominated in dollars, 19% in euros, 12% in yen, and 3% in British pounds. For inward bond investments, 65% of these are dollar-denominated, 16% are euro-denominated, and 14% are yen-denominated. As for “other investments,” mainly loans (assets) and borrowings (liabilities) by financial institutions, assets amounted to about $2.1 trillion and liabilities to about $2.6 trillion, with the currency share in loans being 52% in dollars, 12% in euros, and 35% in yen, and in borrowings 59% in dollars, 7% in euros, and 26% in yen.

For Japan with such a portfolio, a decline in the value of the yen would increase its holdings of assets denominated in foreign currencies when converted to yen. Furthermore, having relatively few liabilities denominated in foreign currencies would allow a weaker yen to have a positive impact on net external assets because liabilities are unlikely to grow rapidly as a result of a weaker currency.

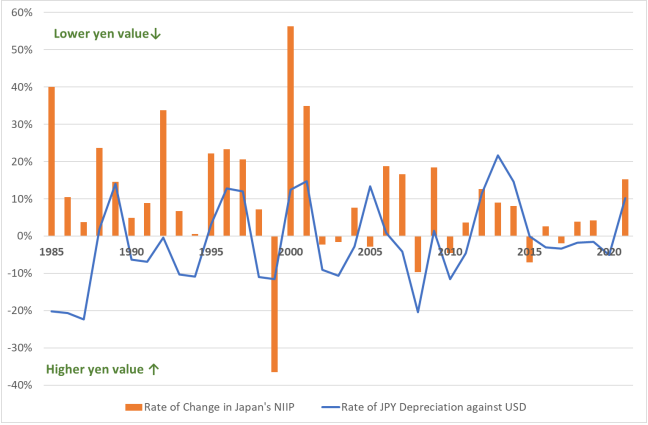

Figure 5 illustrates the rate of change in net external assets (orange bar) and the rate of depreciation in the yen's exchange rate against the dollar (blue line). The figure shows that net external assets tend to increase in years when the yen depreciates. Of course, changes in the exchange rate alone cannot fully explain the changes in net external assets, as equation (3) shows. Furthermore, Figure 5 shows only the movement of the yen-dollar exchange rate, not including the rates of yen depreciation against other major currencies (Note 6).

Lane and Shambaugh (2010) and Bénétrix et al. (2015) introduced a method for estimating valuation effects by collecting or estimating data as shown in Table 1 for over 100 countries and regions for the period 1990-2012. They used the Lane and Milesi Ferretti (2001, 2007, 2017) database to calculate the share of investment types (FDI, equity, debt, and other investments) in assets and liabilities, respectively, and the size of total asset and liability exposure for each country. They also estimated the currency composition of each investment type in each of the asset and liability categories using domestic and international sources, including international organizations and central banks (Note 7).

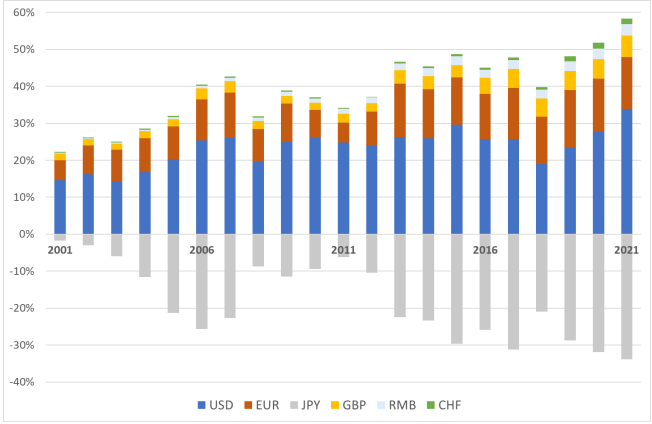

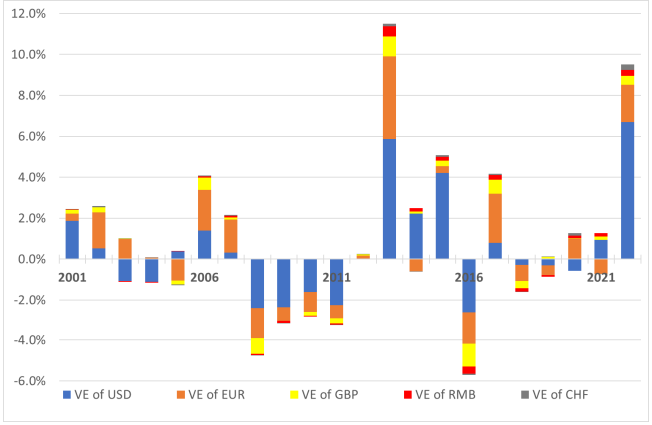

Focusing on Japan, Figure 6 illustrates the weights of the valuation effects of six major currencies (the U.S. dollar, euro, Japanese yen, Swiss franc, Chinese yuan, and British pound) for the period from 2001 to 2021. Here, there are several interesting observations drawn from the figure.

First, with the exception of the Japanese yen, all of the major currencies have positive weights. This means that a country's external wealth increases when other major currencies appreciate (i.e., when the domestic currency (= the yen) depreciates).

The dollar’s share was around 20% from the late 2000s through the 2010s, but has been on the rise in recent years. The euro remains the second currency, but shows no sign of catching up to the dollar share. The shares of other currencies are also even lower and show little change.

A weaker yen will increase profits for individual investors and financial institutions such as banks and insurance companies that make large foreign investments. In fact, in the April-September period of 2022, the Bank of Japan posted a record high (1,592.4 billion yen) in its surplus, or final profit. About half of this amount is attributable to foreign exchange gains generated when foreign currency assets are converted to the yen due to its rapid depreciation (Note 8).

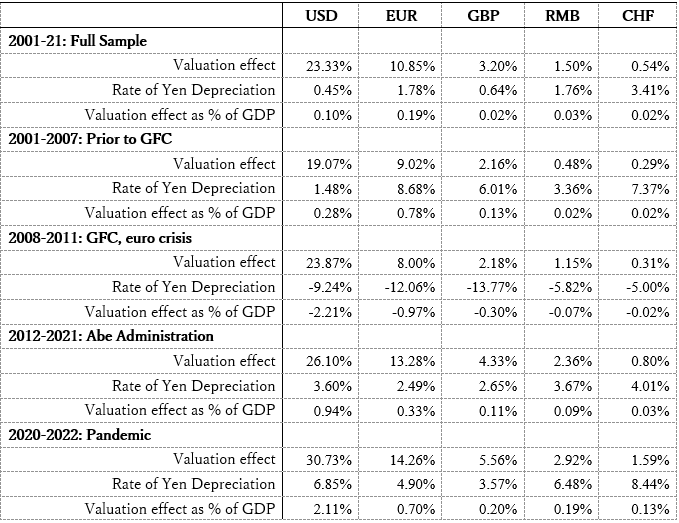

Let us quantify the magnitude of the valuation effect caused by exchange rate fluctuations using the calculation method based on Lane and Shambaugh (2010) and Bénétrix, et al. (2015). Table 2 and Figure 7 show the valuation effect as a percentage of GDP if the value of major currencies depreciated 1% against the yen. Since the calculations are based on actual exchange rate fluctuations, the valuation effect would be positive when the yen depreciates, and negative when the yen appreciates.

Source: Compiled by the author.

The annual average valuation effect of the dollar over the entire sample period 2001-2022 is 23%, or 0.10% of Japan's GDP (Table 2).

During the subsample period from 2008 to 2011, which is characterized by the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008 and followed by the euro crisis in 2010-11, the yen appreciated against all major currencies (Note 9), resulting in the valuation effect of -2.2% for the dollar and -1.0% for the euro, both as a percentage of Japan's GDP.

In 2012, Shinzo Abe was reelected as prime minister and Haruhiko Kuroda became governor of the Bank of Japan (BOJ). The prime minister and the BOJ cooperated to implement the ultra-easy monetary policy known as “other-dimensional” monetary easing. This has alleviated the long-running trend of the strong yen and weakened the currency against other major currencies. Over the 10-year period since 2012, the dollar’s valuation effect averaged 0.9% of Japan's GDP and that of the euro 0.3% of GDP.

With the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the yen lost value against the U.S. dollar, especially after 2021, and fell significantly in 2022. Reflecting this, the valuation effect in 2022 is quite large over the three-year period 2020-22 (Note 10), with an annual average of 31% for the dollar and 14% for the euro. The estimated level of impact is as high as 2.1% (as a percentage of 2021 GDP) for the dollar (10.7 trillion yen) and 0.7% for the euro (3.9 trillion yen).

Exchange rate fluctuations and their valuation effects can also affect the lives of those who may not appear to be interested in FX investments.

A prominent example is Japan’s National Pension Plan and Employees’ Pension Plan. These pension funds are managed by the Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF). As of the end of 2022, it is the world's largest pension fund, with 197 trillion yen under management. Its investment returns are comparable to those of other major pension funds in the world. GPIF invests the accumulated funds in domestic bonds (e.g., government bonds) and stocks, as well as in foreign bonds (e.g., U.S. government bonds) and stocks.

For a long time and until recently, the proportion of pension funds invested in foreign assets had been kept low because they were viewed as high-risk. However, in response to a recommendation from experts that in order to increase returns on pension investments, the GPIF invested more in foreign assets, though they can be somewhat risky. In 2014, the portfolio was substantially changed from a conservative stance centered on domestic bonds to one that includes higher-risk assets such as foreign bonds and stocks. As of FY2001, the pension fund portfolio consisted of 68% domestic bonds, 18% domestic stocks, 3% foreign bonds, and 10% foreign stocks. As of 2023, the GPIF portfolio has a target ratio of 25% for each of the four asset types.

The pension reforms related to portfolio management have caused exchange rate fluctuations to have a greater impact on fund management. Yen depreciation, like what is happening now, has more positive impacts on the yield of pension funds. In fact, the GPIF's investment returns have risen in the last few years. Of course, depending on future conditions, the yen may well return to an appreciation trend, in which case the investment returns of the GPIF and financial institutions could be negatively affected (like what happened in the aftermath of the GFC). In fact, many financial institutions have experienced capital losses as bond prices fell due to repeated Fed rate hikes in 2022 and 2023. The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in March 2023 is the best example, and the GPIF's rate of return also declined somewhat in FY2022. However, while the rate of return has somewhat declined, it should not necessarily lead to the argument that the GPIF should lower its tolerable risk level.

At the very least, I can conclude that currency fluctuations have a greater impact on our wealth and our lives. This is not a matter that should simply be left to FX investment experts.

5. Concluding Remarks

While commentators have been discussing the decline in Japan’s national strength and wealth, I recently feel that there are misunderstandings and baseless exaggerations about Japan’s balance of trade and net foreign assets. It is quite common for misunderstandings and lack of knowledge to lead to disputes between countries or political divisions among citizens. To help avoid that, I have attempted to clarify the definitions and relevant data about the balance of payments and Japan's external wealth in a way that is as easy to understand as possible for those who are not specialists in international macroeconomics. It was a difficult task since the subject is not easy to understand even for economic experts.

Although I did not emphasize it thus far, it is often pointed out that Japan seems to pursue a “low-risk, low-return” strategy in its balance sheet management. The country’s tendency to have low risk tolerance may be due to the traumatized experience of the bursting of the bubble economy in the early 1990s. The aftereffects of this tendency seem to be lingering, as exemplified by the fact that about 93% of Japan’s government bonds are owned by Japanese. As the birthrate continues to decline and the population ages, not only labor income but also interest income and pensions are becoming increasingly important issues. I hope this report provides some food for serious thought.

This article first appeared in Japanese in the June 2023 edition of the Securities Analysts Journal.

English translation by the author.

June, 2023 Securities Analysts Journal