The decline in Japan's rural population shows no sign of stopping. A population change in an area is a function of two factors, namely, natural change calculated as a difference between the number of births and that of deaths, and net migration calculated as a difference between inflows and outflows. In most prefectures, both factors have been consistently negative. Population changes are dependent, in part, on the availability of attractive job opportunities. Our estimates of the number of companies—the source of labor demand—by prefecture predict that the situation will become even more difficult for rural prefectures in the coming years.

The aging of the local population translates into a decrease in the number of startups, and the aging of business managers into an increase in the number of business closures. Based on the assumption that the exit and entry rates by age group of managers in each prefecture will remain unchanged, our estimates show that the number of private-sector companies in Japan will decrease from 4.02 million in 2015 to 2.95 million in 2040, with the number of employees dropping by 21% from 58.46 million to 45.98 million. The changes will not be uniform across the nation. As a general trend, the gap between urban and rural areas are inclined to widen with a higher degree of concentration observed in the metropolitan areas. Many of today's incumbent managers are post-war baby boomers. In the coming years till around 2025, a period in which most of those in this particular generation will be entering retirement, the number of companies and employees will decrease at an accelerated pace. As a result, the pace of decrease in the number of employees will temporarily exceed that in the number of working-age population. The phenomenon will be more conspicuous in rural prefectures.

♦ ♦ ♦

As of 2015, 28.4% of Japan's population was living in the greater Tokyo area, defined as Tokyo and its three neighboring prefectures. However, the degree of concentration was even more pronounced when measured in terms of bank loans, with the greater Tokyo area accounting for 52.3% of the total amount of loans outstanding as of the end of 2015. The area's share in bank deposits also increased to 44.5% today, with portions of deposits previously held in accounts with banks in rural areas inherited by heirs living in the greater Tokyo area and thus transferred to their bank accounts located in the area.

In order to break the vicious cycle of population decline, low fertility, and population aging, the government needs to intensify efforts to support business startups and facilitate business succession in rural areas. At the same time, it is also imperative that existing companies make efforts to create attractive job opportunities by taking advantage of the characteristics of the region in which they operate. What is required for that is human resources capable of generating jobs.

The government has launched a program designed to supply professional human resources—i.e., those capable of offering management support or equipped with special skills and expertise—to businesses in rural areas. Local service offices—one in each prefecture—have received some 16,000 inquiries for advice and support, resulting in the employment of some 1,600 professionals by local businesses. As a next step, it is necessary to develop channels for facilitating the flows of more diverse human resources from urban to rural areas.

At present, the focus of the program is on supplying human resources who can serve as a right-hand man to the leader of a small and medium-sized enterprise (SME). However, the government should consider expanding the program to supply business leaders, thereby facilitating business succession and promoting startups in rural areas. Chambers of commerce and industries, local financial institutions, and governmental financial institutions are already helping local companies by introducing talent and providing information, consulting services, and financial assistance. They should further enhance these projects by working in tandem with local communities for which they serve.

♦ ♦ ♦

Partly in response to the government's request, most municipalities drew up their population visions and revitalization plans by the end of March 2016, and have since been working toward realizing them. Although results from these initiatives do not come overnight, some municipalities are getting on track. What is common to these municipalities is the presence of capable leaders—whether in the public or private sector—to implement strategies. There have been government-sponsored programs designed to help municipalities with the implementation of their respective job creation strategies by providing financing and offering advisors.

However, many municipalities lack human resources trained to play leading and supporting roles in generation jobs and creating new businesses. It requires an ample supply of human resources with relevant professional skills to enable municipalities to put their strategies into action. In the United States and Europe, conscious efforts have been made to develop human resources essential to the implementation of local job creation strategies and offer them opportunities to demonstrate their skills.

In a bid to develop and secure human resources necessary for the full-scale implementation of regional revitalization projects, the Japanese government has also launched an e-learning site called "Chiho Sosei (Regional Revitalization) College" to offer online seminars on practical skills and knowledge, mobilizing resources and expertise from the public and private sectors. The college also offers on-the-job training as needed to enable participants to learn practical knowledge and skills.

Its curriculum is designed to develop human resources capable of producing efficient strategies by utilizing objective data and implementing the plan-do-check-act (PDCA) cycle properly. Specifically, the college offers the following three types of courses: 1) courses for general producers such as those on the perspective of management of regional economies, means for securing financing, and the promotion of local industries; 2) courses for sector-specific producers such as those on tourism and destination marketing organizations (DMOs), town planning and development, revitalization of agriculture, and local branding; and 3) courses for local community leaders such as those on the relationship between community revitalization and commerce, and case examples of community-led initiatives for town planning, human resources development, and job creation.

Assuming a new responsibility requires a new perspective and a new set of knowledge and skills. Above all, one must have enthusiasm for the revitalization of the region and the trust of the people living there and of participants of the project.

However, municipalities make personnel changes frequently, and those assigned to divisions in charge of the promotion of local industries and job creation are no exception. It is often the case that someone who played a key role in developing a strategy has been transferred to another division by the time the strategy is implemented. Given the frequency of personnel changes typically observed in municipalities, officials assigned to a certain division have just enough time to learn and get accustomed to the tasks and procedures taken over from their predecessors, and will be transferred to another division just as they become ready to tackle challenges. Under such circumstances, they cannot fulfill what they are supposed to do and problems are left unresolved. The customary practice of rotating personnel from one section to another inhibits municipal officials from winning the trust of stakeholders, because they cannot even flesh out a strategy for creating new industries based on a full understanding of the technologies and characteristics of key industries.

The same holds true for major companies' local offices and branches, where office and branch managers or other senior employees are changed frequently. Thus, it is also difficult in the business sector to cultivate human resources attached and dedicated to a specific region. Japanese companies should consider expanding the quota for local hires in recruiting career-track employees, in addition to those recruited by the head office. Both municipalities and businesses need to change their systems for personnel changes and transfers in order to develop future leaders rooted in their respective local communities.

♦ ♦ ♦

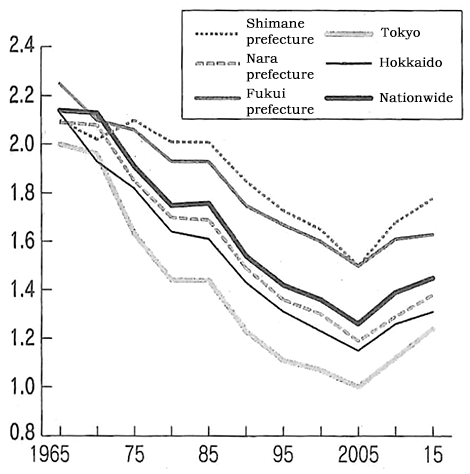

Japan's total fertility rate has improved slightly in recent years. However, the number of women in their 20s through 30s, who together account for more than 90% of births, has been on a decline, resulting in a downward trend in the number of birth per year. The total fertility rate varies significantly across regions and the disparities are widening (Figure).

The total fertility rate—which is defined by the percentage of unmarried women, average age of women at their first marriage, and total marital fertility rate—is subject to the influence of various factors, including the level of income, economic and employment environments, percentage of non-regular workers (those other than permanent fulltime employees), commuting time to work, and environment for and cost of child-rearing. In particular, those associated with working style reform have a significant impact. The fertility rate is lower in areas characterized by a high ratio of workers working 60 hours or more per week, long commuting time to work, a sharp drop in the percentage of women at work after childbirth, and low availability of childcare facilities. In recent years, women have been showing significant geographic mobility, even exceeding the level of men. Unlike in the past, when women tended to stay with their parents after finishing school, more women are choosing to move to areas that offer attractive job opportunities.

The government's Council on Overcoming Population Decline and Vitalizing Local Economy in Japan has pointed to the importance of local initiatives in addition to nationwide support measures. Thus, prefectural councils on working style reform have been established, bringing together various local stakeholders—i.e., local governments, labor and employers' organizations, financial institutions, universities, etc.—to implement reform according to the reality of each region, thereby helping enhance local businesses' productivity and ability to hire employees.

This has prompted ambitious reform initiatives in some regions, but there are also those that have not been forthcoming in terms of both perception and action. It is necessary to provide outreach support services, which entails reaching out directly to companies to offer advice, rather than simply establishing one-stop consultation counters and wait.

The government should help prefectural councils to invigorate their activities and enhance financial support to them. In particular, it must rev up efforts to secure and make available human resources capable of offering advice on working style reform. Currently, certified social insurance and labor consultants and certified SME management consultants are serving as such advisors, but services provided by them are insufficient in both quality and quantity. The kind of advisors in demand are those capable of providing advice from a comprehensive perspective. The government should establish a new qualification system to help develop human resources capable of filling the role.

Developing local economies is about developing local human resources. A wide variety of responsible and trusted professional human resources are needed.

* Translated by RIETI.

September 28, 2017 Nihon Keizai Shimbun