The Japanese government is to make preschool education and childcare at licensed nurseries free, starting from October 2019. Low-income households exempted from paying resident taxes with children up to age 2, and all households with children aged between 3 and 5 will be eligible for free childcare at licensed nurseries. This article assesses the reform from the perspective of policy objectives.

♦ ♦ ♦

The critical objective of childcare policy is to enable those who want children to have them. There are two significant factors preventing people from doing so.

The first is that most low-income earners are too poor to bring up children healthily. Many young people are hesitant to get married for this reason.

Second, middle-income parents living in cities child may face the situation that their child is only in waiting lists for nurseries. Then they either have to put the child in an unlicensed nursery or accept that one parent stays home to care for the child. Uncertainty regarding the availability of a place at a nursery is making it impossible for young couples to predict future childcare costs, which discourages them from having children.

Introducing free nursery services will not solve these problems.

For one thing, childcare charge is already free for the impoverished households(i.e., those receiving public assistance) and meager for other poor households. In order to reduce child poverty, making nurseries free of charge will not contribute much. At the very least, an establishment of a negative income tax system would be necessary.

Under the new system of free childcare, the benefits are more significant for households with higher incomes. Therefore, the middle- and high-income earners would consume the funding that could have been used to lift children out of poverty.

What is more, making licensed nurseries free of charge will boost the amount demanded for licensed nursery services, substantially increase the number of waitlisted children. Making licensed nurseries free of charge under these circumstances will give no benefit to parents whose applications are unsuccessful.

Eliminating the waitlist for the nursery is the most pressing policy issue in childcare. Waitlisted children are those who are unable to get a place at a licensed nursery or certified nursery due to excess demand. A licensed nursery is a facility licensed by the governor of a prefecture as having satisfied the standards for establishment under the Child Welfare Act. This governs such matters as the space of the facilities and the number of nurses. The standards for establishment are strict, so the cost per child is high.

According to information disclosed by Itabashi City in Tokyo, the monthly cost per child of a licensed nursery is ¥420,000 for a child under one year old, ¥210,000 for a 1-year-old child, and ¥110,000 for a child aged four years or over. However, the central government covers a significant part of the cost of licensed nurseries, and hence parents pay meager fees for licensed nurseries. A parent with an annual income of ¥5 million would pay monthly childcare fees varying between less than ¥30,000 (for a child aged one year or under) and less than ¥20,000 (a child aged four years or over).

The selection process for children to enroll in licensed nurseries is a rationing system. The local government calculates the supply of childcare services corresponding to the number of people needing child care in that area and then provides those services based on a specific criteria for enrollment. Consequently, the parents must enroll their child in a licensed nursery as specified by the local government rather than concluding enrollment agreements directly with the licensed nurseries.

In large cities, many parents are unable to enroll their children due to the shortage of licensed nurseries. The enrollment criteria give a high priority to the households with both parents working full-time while giving a low priority to a parent working part-time. Accordingly, a child from a high-income household with both parents working full-time would get a place at a licensed nursery, while a child of low-income households with one parent working parttime would not.

Raising childcare fees for middle- and high-income earners should reduce the supply shortage. In terms of economics, childcare waiting lists represent a supply shortage in licensed and certified nurseries resulting from government regulation of the fees for licensed nurseries too far below the supply-demand equilibrium level. The new policy of free childcare will only lengthen the waitlist for licensed nurseries because it will further reduce childcare fees—which were too low in the first place—to zero.

♦ ♦ ♦

Adopting orthodox measures to eliminate the child care waiting list will undo the damage to be caused by the new government policy of providing free nursery service. These measures that I propose in the following could be implemented without any additional costs.

The first is to eliminate the incentives for creating the excessive demand for nursery services for children under the age of 1 that exist in the Japanese system.

At present, most mothers with children under the age of 1 can take childcare leave until their child turns 1. Nevertheless, many mothers return to work soon after giving birth by giving up childcare leave. This is because when they try to enroll their child in a nursery upon reaching the age of 1, they find that the nursery is already full of children who enrolled before reaching that age 1. In order to ensure that a nursery accepts their child, mothers have to place their child before it reaches 1. Accordingly, many children under the age of 1 are in childcare unnecessarily.

The national standard for the number of licensed childcare nurses required in a licensed nursery for children under the age of 1 is double the number required for the children of the age of 1 and over. The increase in the number of children under the age of 1 in licensed nurseries has been reducing the number of places available at nurseries for older children. This has been unnecessarily increasing the waiting lists for nurseries.

A solution to this problem is to abolish licensed nursery services for children under the age of 1. This would free licensed childcare nurses from the need to care for children under the age of 1 and ensure that there were sufficient places for children aged one and above, thereby giving parents the option of looking after their child at home until the age of 1 by taking advantage of child care leave.

At the same time, local governments can provide financial support for the cost of childminders or babysitters for mothers who cannot take childcare leave. By adopting this measure, local governments would be able to make a substantial saving compared with providing licensed childcare for children under the age of 1, which costs in the region of ¥400,000 per month. Edogawa Ward, Tokyo, has successfully introduced this measure. It should also be adopted nationwide.

The second proposed measure is to reduce the required percentage of licensed childcare nurses among childcare staff from the current level of 100% to 60%. The required number of childcare staff Tokyo's certified nurseries is equal to that of licensed nurseries.

At Tokyo's certified nurseries, where the requirement for licensed childcare nurses is 60% of that at licensed nurseries, while

No problems have arisen

If the requirement for licensed childcare nurses at licensed nurseries was lowered to this level and personnel other than nurses could, therefore, be used to make up the difference, it would free up licensed childcare nurses from licensed nurseries. would enable an increase in openings of certified nurseries, with a consequent reduction in the number of waitlisted children.

Certified nurseries such as Yokohama Nurseries, founded in 1997, and Tokyo Certified Nurseries, founded in 2001, receive virtually no central government funding. Hence, local government subsidies and childcare fees cover the majority of costs. The average childcare fee of Tokyo Certified Nurseries is approximately ¥65,000, which is higher than at licensed nurseries.

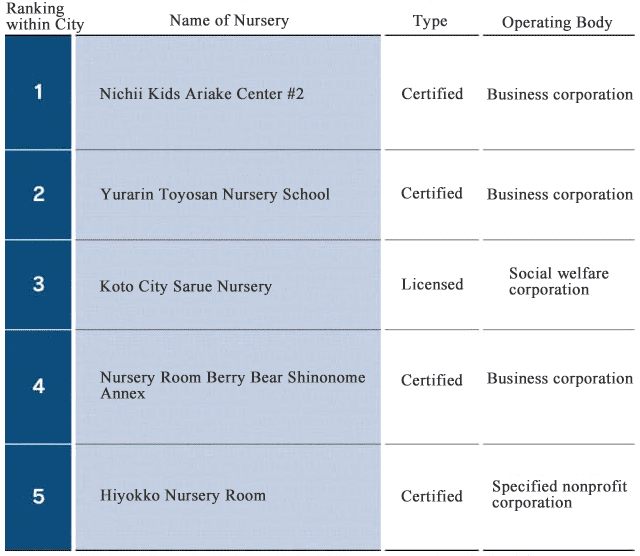

(Koto Ward, Tokyo; FY2019)

The locally funded "certified nurseries" receive just as high ratings as the nationally funded licensed nurseries. This is clear from the ranking of the nurseries that receive the highest ratings from parents and guardians in Tokyo's Koto Ward, shown in the table. Even looking at the average for Tokyo as a whole, certified nurseries are rated higher than licensed nurseries. This is probably because certified nurseries meet the need of users better regarding the content of education, for example. The lower requirement for the number of licensed childcare nurses at certified nurseries has increased quality, if any.

Thus we propose to reduce the required percentage of licensed childcare nurses to the level of certified nurseries. This measure will reduce the number of waitlisted children without compromising the quality of childcare.

After implementing these measures to undo the damage to be caused by the new government policy, the government should start to charge childcare fees at licensed nurseries at levels above those at certified nurseries. The government should then use the resulting financial resources to improve pay and conditions for licensed childcare nurses and to establish a negative income tax system.

* Translated by RIETI.

September 20, 2019 Nihon Keizai Shimbun