Given the US dollar's historical prominence in international currency systems, it can be argued that a large part of its present-day importance is due to inertia. This column analyses the determinants of the utility of four international currencies, focusing on the liquidity premium. It shows that while inertia does have a strong effect on a currency's utility, a liquidity shortage can also reduce the utility of an international currency.

The US dollar was a key currency in the Bretton Woods international monetary system. The monetary authority of the US fixed the dollar to gold, while those of other countries fixed their home currencies to the US dollar under the Bretton Woods system. This maintained the stability of exchange rates between currencies. However, the Bretton Woods system was dismantled in 1971 by the US monetary authority, bringing to an end the US dollar to gold conversion. The dollar's position as a key currency in the current international monetary system remains, even though there is no rule under which it must be used. This phenomenon is known as the inertia of the key currency.

Given that a key currency is chosen for economic reasons that include the costs and benefits of the international currency, a comparison of these factors determines which key currency is quoted in current international monetary policy. Additionally, the inertia of a key currency should be linked to the inertia of costs and/or benefits of holding the international currency. The costs of holding the currency are related to the depreciation caused by inflation in the relevant country. In one way, the benefits of holding an international currency are the result of the utility of holding it.

Various related studies have focused on the individual roles of the US dollar as a key currency in the international monetary system. For example, Chinn and Frankel (2007, 2008) focused on its role as an international reserve currency. Eichengreen et al. (2016) analysed the role of an international reserve currency, investigating whether there was a change in the determinants of the currency composition of international reserves before and after the collapse of the Bretton Woods regime. Goldberg and Tille (2008) analysed the US dollar and other currencies as invoice currencies in international economic transactions. Ito et al. (2013) conducted a survey of all Japanese manufacturing firms listed in the Tokyo Stock Exchange on their preference of invoice currency. The ECB (2015) reported the increasing prominence of the euro as an international currency in terms of its three functions as an international reserve, in international trade, and in financial markets.

In a Sidrauski (1967)-type money-in-the-utility model (Calvo 1981, 1985, Obstfeld 1981, Blanchard and Fischer 1989), real balances of money and consumption are used as explanatory variables in a utility function. We can use this model to analyse the costs and benefits of holding international currencies. In a pair of papers (Ogawa and Muto 2017a, 2017b), we used expected inflation rates and BIS data on the total of domestic-currency-denominated debt and foreign-currency-denominated debt for the euro currency market to estimate a time series of coefficients for international currencies in a utility function. We call these coefficients the utility of international currencies.

Liquidity risk premium in an international currency affects its utility

In a later paper (Ogawa and Muto 2018) we investigated what determines the utility of four international currencies: the US dollar, the euro, the Japanese yen, and the British pound. We used a dynamic panel data model on the entire sample period from 2006Q3 to 2017Q4 to analyse the problem using generalised method of moments (GMM). Specifically, a liquidity shortage in terms of an international currency means that it is inconvenient for economic agents to use the relevant currency for international economic transactions, reducing its utility. In this analysis we focus on the liquidity premium, which represents a liquidity shortage in terms of an international currency. We conducted an empirical analysis of whether the liquidity risk premium in an international currency affects its utility.

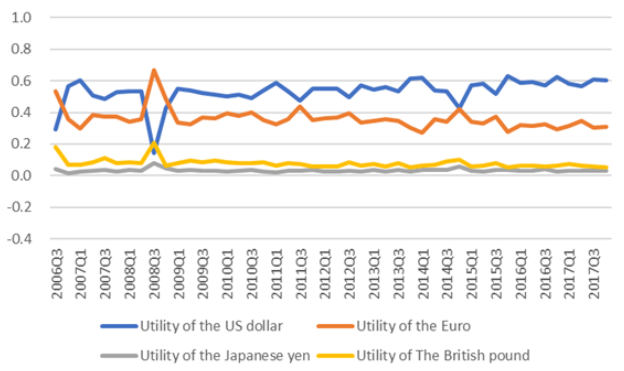

Figure 1 shows the time series of the utility of four international currencies that were estimated by using an equation based on the money-in-the-utility model. Throughout the period, changes in the utility of the US dollar, the euro, the Japanese yen and the British pound fluctuated around 0.55, 0.35, 0.02 and 0.08, respectively. We found that the utility of the US dollar sharply decreased while that for other currencies increased in 2008Q3. In particular, the utility of the euro greatly increased during that quarter.

Note: the four lines represent a time series of estimated coefficients for four international currencies (the US dollar, the euro, the Japanese yen, and the British pound) in a money-in-the-utility function. The coefficients were estimated from share of holdings of an international currency and expected inflation rates with a real interest rate estimated at 2.0%. We used BIS data on total of domestic-currency-denominated debt and foreign-currency-denominated debt of the euro currency market as the share of holdings of an international currency. The expected inflation rates are the calculated rate of change of actual CPI level and expected CPI level estimated under the assumption that the price level of each period follows ARIMA (p, d, q) process.

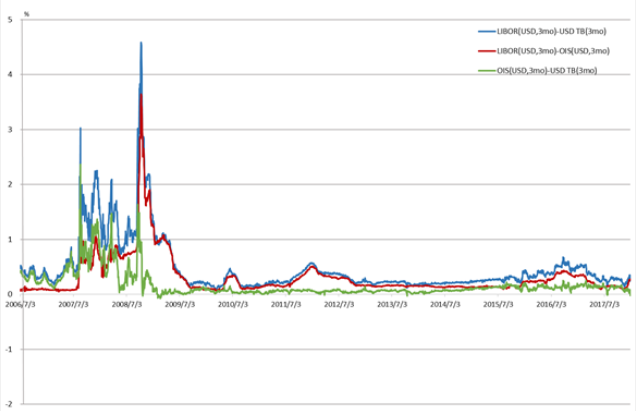

Figure 2 shows movements in three spreads of LIBOR (USD, 3 months) minus the Treasury Bills (TB) rate (USD, 3 months), LIBOR (USD, 3 months) minus the Overnight Indexed Swap (OIS) rate (USD, 3 months) (the credit risk premium), and the OIS rate (USD, 3 months) minus the TB rate (USD, 3 months) (the liquidity risk premium). We found that the US dollar liquidity shortage continued from 2006 to 2008. However, it decreased to a level less than 0.1% after the FRB started its quantitative easing monetary policy in late 2008 when at the same time it concluded and extended currency swap arrangements (Note 1) with other major central banks to provide US dollar liquidity to other countries.

Note: data: Datastream, Credit risk premium= LIBOR (USD, 3months) minus OIS rate (USD, 3 months), liquidity risk premium = OIS (USD, 3 months) minus US TB rate (USD, 3 months)

We obtained the following results from our empirical analysis. First, the change in the currency's utility in the previous period has a significant positive effect on the change of the currency's utility in the current period. This suggests that the utility of a currency tends to fluctuate in the same direction as the change in the previous period. For example, if the utility of the currency declines, we assumed that the currency is less likely to be used than in the previous period, which then continues in the next period. Second, the change of liquidity risk premium has a significant negative effect on the change in utility of the currency. This suggests that a liquidity shortage reduces the utility of an international currency. Third, the change in the share of capital flows has a significant positive effect on the change of utility of the currency. This suggests that changes in economic scale, specifically capital flows, affect the utility of the international currency.

We extracted policy implications from the empirical results. As mentioned above, liquidity risk premium and capital flows influenced the utility of the international currency. If the monetary authorities are striving to internationalise their home currencies, it is necessary to focus on these variables. It is considered that the utility of the international currency increases by conducting policies that increase the liquidity of the currency or increase international capital flows. It might be possible to push internationalisation of the home currencies through this increase of utility of the international currencies.

This article first appeared on www.VoxEU.org on July 26, 2019. Reproduced with permission.