The study of global value chains has become increasingly relevant as production becomes more and more fragmented across countries. This column uses evidence from Japan to evaluate recent theories that such chains have caused some of the country's industries to become less competitive. The findings suggest that considering production for exports and domestic sales separately may provide a more complete picture of firm heterogeneity within industries, and a more complete picture of interconnected countries at the industry level.

A widespread traditional perception is that the Japanese manufacturing sector has strong forward linkages in global value chains (GVCs), i.e. Japanese firms' value added accounts for an important share of foreign final demand and Japanese firms therefore benefit substantially from foreign final demand (e.g. OECD 2018). However, recent trade and other statistics imply that some industries in Japan's manufacturing sector, such as electric machinery, have been losing competitiveness and forward linkages may be weakening. In this column, we present and discuss evidence on these trends based on a new study we recently completed (Ito et al. 2017).

A tool to measure the significance of GVCs

The role of GVCs has recently become an important topic due to the increased fragmentation of production across countries and industries. Multi-country input-output tables (MIOTs) have been extensively used to measure the significance of GVCs (e.g. Koopman et al. 2014). Several initiatives, such as the joint initiative by the OECD and the WTO on Measuring Trade in Value Added (TiVA) (Piacentini and Fortanier 2015) and the World Input-Output Database initiated at the University of Groningen within the framework of a European Commission project, have attempted to construct such tables (Timmer et al. 2015). The idea underlying these databases is to link national supply-use tables via international trade flows.

How to accommodate firm heterogeneity in MIOTs

Both theoretical and empirical research suggests that there is considerable heterogeneity across firms and their export activities within the same industry (Melitz 2003, Bernard et al. 2007), and recent studies using MIOTs have sought to incorporate such heterogeneity by splitting industries into groups of firms in terms of their size, ownership, trade mode, and so on (Ahmad et al. 2013, Ma et al.2014, Fetzer and Strassner 2015). However, there are few such studies focusing on Japan, even though neglecting such heterogeneity may produce biased results in analyses relying on MIOTs.

Our study attempts to fill this gap using a unique Japanese manufacturing plant-level dataset. Specifically, using matched data from the Economic Census for Business Activity and the Basic Survey on Wage Structure, we split output in 16 industries of Japan's manufacturing sector in the OECD Inter-Country Input-Output (ICIO) table into output for exports and domestic sales to reflect heterogeneity across firms. Thus, input-output transactions are divided into production for exports and production for domestic sales for each of these 16 industries. To examine the GVC participation of Japanese manufacturing plants, we compute TiVA indicators related to forward linkages (Note 1) and backward linkages (Note 2) from our extended ICIO table, and compare them to indicators computed from the original OECD ICIO table.

Japan's manufacturing forward linkages in GVCs

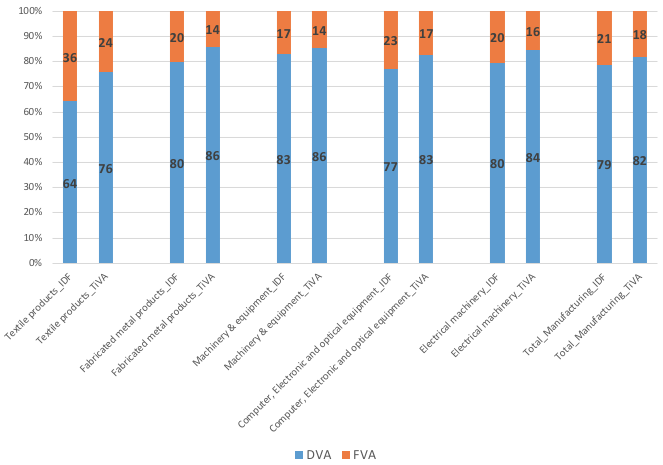

Figure 1 shows the share of domestic value added (DVA) in Japan's exports as well as the foreign value added (FVA) in Japan's exports, in our estimates (denoted by ‘IDF’) and the corresponding OECD TiVA statistics (denoted by ‘TiVA’) for the manufacturing sector overall and several industries in 2011 (Note 3). We find that the domestic value added computed from our split ICIO table is lower in the industries shown than the domestic value added computed from the original ICIO table (Note 4). The lower domestic value added in our estimates means that the foreign value added is higher than in the original ICIO table.

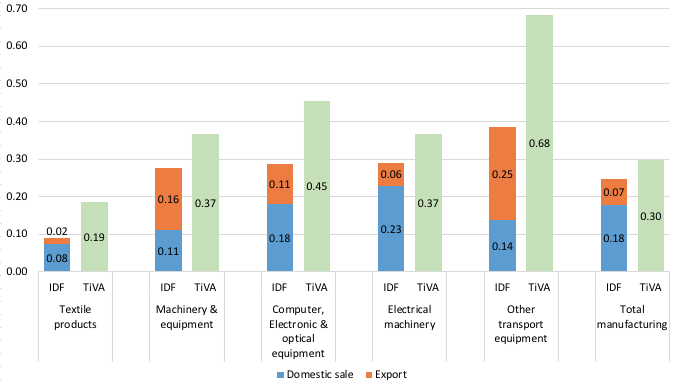

Another indicator of forward linkages in GVCs is the domestic value added embodied in world final demand. Figure 2 compares our estimates with those reported in the TiVA database, and shows that our results are lower than the TiVA results for the industries shown and the manufacturing sector overall (Note 5). Note that companies in these industries tend to rely on outsourcing as well as outward foreign direct investment (FDI) and intra-industry trade.

Thus, when we consider manufacturing plant heterogeneity in production for exports and production for domestic sales, we find that both the domestic value added in Japan's export and the domestic value added embodied in foreign final demand are lower than the results based on the ICIO table, not taking such heterogeneity into account.

Explaining the differences in Japanese manufacturing sector's forward linkages in GVCs

Why are our estimates lower than the TiVA estimates? The reason is that our split ICIO table distinguishes between Japan's production for exports and production for the domestic market, and therefore reflects more accurately the actual situation of Japanese firms' internationalisation—namely, the fact that only a limited number of firms with high productivity are engaged in international activities. That is, while Japan is widely perceived as a country with highly competitive manufacturing firms with substantial forward linkages, only a relatively small number of firms are actually engaged in export activities to satisfy foreign final demand, and, of the firms engaged in international activities to meet foreign final demand, many generate part of the value added abroad through FDI, intra-firm trade, offshoring, and so on (i.e. value added induced by foreign final demand leaks to other countries). On the other hand, the large majority of firms in Japan conduct transactions only with domestic firms.

The input-output structure of production for export is quite different from that of production for domestic sale. Thus, the indicators of forward linkages estimated from our split input-output table based on firm-level data reflecting these differences are lower than the original TiVA indicators.

Factor input differences between production for export and production for domestic sale

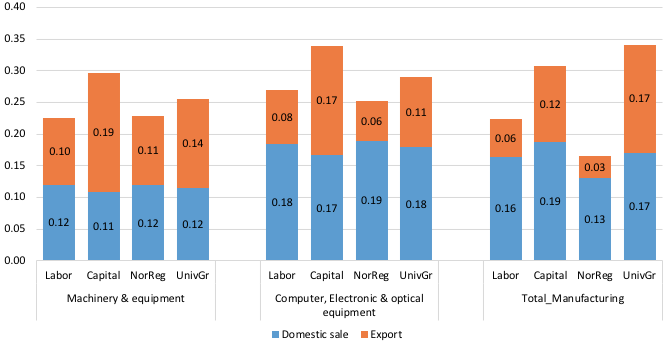

It is likely that firms engaged in international activities are more capital-intensive and skill-intensive than firms not engaged in international activities. To examine whether this is indeed the case, we calculate factor inputs embodied in world final demand in production for exports and production for domestic sales using our split ICIO table. The results, shown in Figure 3, indicate the following.

- First, we find that production for domestic sales makes up a relatively large portion of Japanese factor inputs embodied in world final demand, meaning that a substantial part of production for domestic sales is used as inputs for production for export. Thus, production for domestic sales benefits from foreign final demand via indirect linkages.

- Second, the input of capital and high-skilled labour (university graduates) in production for domestic sales is higher than in production for exports in the computer, electronic, and optimal equipment industry and in the manufacturing sector overall (about the same for university graduates). In fact, we obtain this result for most industries in our study. Thus, we conclude that in the case of Japan the input of capital and high-skilled labour in production for domestic sales benefits more from foreign final demand than in production for exports.

- Third, capital and high-skilled labour are embodied in foreign final demand to a higher extent than labour of regular and non-regular workers (indicated as "Labor" and "NonReg") in the industries shown in Figure 3. Again, we obtain this result for most industries in our study. Thus, we conclude that capital and high-skilled labour benefit to a higher extent from exports and foreign final demand than less-skilled labour (regular and non-regular workers).

In sum, we find that in most industries' forward linkages are capital and skilled-labour intensive. Thus, we would expect an increase in foreign demand to induce a higher increase in demand for capital and high-skilled workers than for less-skilled workers.

Conclusion

Our findings based on Japanese firm-level data suggest that considering production for exports and production for domestic sales may provide a more complete and better picture of firm heterogeneity within industries in ICIO tables. Moreover, as we document for the case of Japan, the resulting TiVA indicators present a more complete picture of the interconnected countries through backward and forward linkages in global value chains.

Editors' note: The main research on which this column is based first appeared as a Discussion Paper of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) of Japan.

This article first appeared on www.VoxEU.org on January 23, 2018. Reproduced with permission.