Whether incumbent firms deter new entrants in a more concentrated market has been of major concern to antitrust authorities. This column introduces empirical evidence on the relationship between market concentration and entry in the intermediate goods market, using unique data from the Japanese auto market. The findings show a U-shaped relationship, whereby entry decreases and then increases as the market concentrates.

Introduction

Do incumbent firms deter new entrants in a more concentrated market? Economic theories show both possibilities. Prospective entrants have an incentive to enter a monopolistic market because of expected high profits. On the other hand, concentrated markets could make it probable for incumbents to collude in order to deter new entrants. Empirical evidence has supported, by and large, the latter.

Less attention has been paid to two important issues, however.

- One is the analysis of the intermediate goods markets.

It is well recognised that separating final and intermediate goods markets matters, given their different nature (Katz 1989). Particularly, the important role of a vertical contract between buyers and sellers in intermediate goods markets could strengthen the relationship between market concentration and entry (Note 1). However, previous research has ignored this point, mainly due to data limitation.

- The other issue is the definition of 'market', which is crucial in determining empirical results.

Many authors have simply used the market boundaries provided by the compliers of official data. However, it is difficult to choose among market definitions, and the official definitions are often inappropriate (Schmalensee 1989). In the analysis, I define market at the buyer-product level. This setting is crucial in analysing the Japanese auto parts industry, where an automaker typically keeps a relationship with two potentially competitive suppliers for each auto part (Konishi et al. 1996).

The analysis makes use of a unique dataset that tracks auto parts transactions between automakers and auto parts suppliers in Japan during the period 1990 to 2010 (Note 2). Entry is measured in gross term at the seller-buyer product level (Note 3). The market concentration is measured by the Herfindahl index.

Is the relationship between market concentration and entry non-linear?

Before the main results, stylised facts are overviewed briefly.

- First, auto parts markets in Japan are duopolistic.

The mean number of incumbent sellers (i.e. auto parts suppliers) in the market is 2.3. The duopolistic nature can be observed when the sample is divided by types of product.

- Second, the market is highly concentrated.

The mean Herfindahl index is around 0.7 (Note 4).

- Third, entry accounts for a large part of transactions.

Roughly one-third of total transactions in 2008 are comprised of new transactions that did not exist in 2002.

- Fourth, multi-product firms have a significant role.

Around 57% of sellers are multi-product firms.

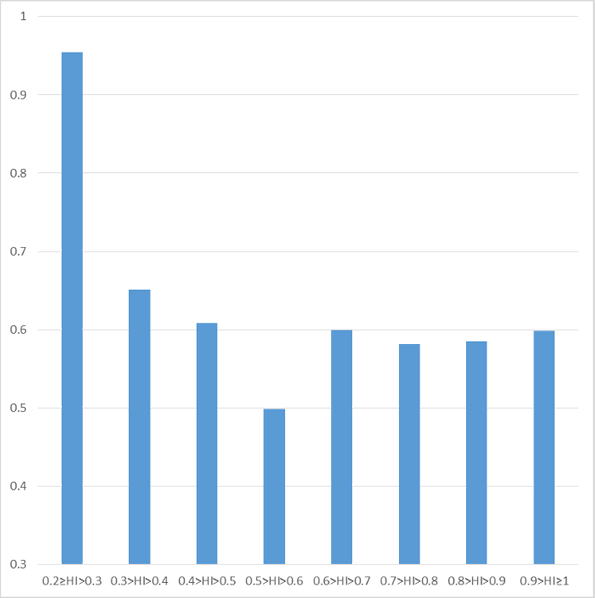

Is there a relationship between market concentration and entry? Figure 1 implies a U-shaped relationship between market concentration and entry. The x-axis is categorised according to the degree of market concentration as measured by the Herfindahl index. The y-axis shows the relative entry index (REI) as measured by the ratio of the number of new transactions that occurred during the period 2002 and 2008 to the number of markets in 2002 for each concentration degree. The results are consistent with prior research for the markets with a relatively low degree of concentrations ranging from 0.2 to 0.6. However, it seems that the relationship turns positive for the range from 0.6 to 1. To test the hypothesis of the non-linearity in a formal way, regression analyses were undertaken with various robustness checks. The results supported the hypothesis (Note 5).

What causes the U-shaped relationship?

One explanation is in the negative correlation between the size of new entry and market concentration, suggesting that potential entrants in concentrated markets aim for a niche product. In a highly concentrated market, incumbent firms have less incentive to deter new entrants as long as potential competitors do not threaten their established transactions with buyers. The models produced in small volume are probably outsourced to such new entrant firms.

Another explanation is that impediments to new entrants are low because of the dominant role of the multi-product firms. As already mentioned above, more than half of sellers are multi-product. In addition, diversification of incumbent firms rather than start of new businesses accounts for a large part of entry. These facts imply that a potential entrant already sells several products to a buyer. Thus, incumbents' cost advantages over potential entrants become small.

Does the U-shaped relationship still hold when the market is defined at a different level? I tested the product level, instead of the product-buyer level, and the U-shape relationship between market concentration and entry is completely gone.

Policy implications

The results obtained from my study have implications for operating antitrust laws, particularly concerning transactions with exclusive conditionality. Antitrust authorities employ market concentration to examine illegality, and it is recognised that the higher the market concentration, the more likely that the incident is against the law. However, the empirical results show that the relationship between market concentration and entry is non-linear, probably resulting from the multi-product nature of firms. This could draw attention to firm attributes in investigating market structure. The results also highlight the significance of defining a market. The empirical results were quite different, depending on the level of market defined. This could alarm antitrust authorities to pay careful attention to drawing a market scope in investigating the incident.

This article first appeared on www.VoxEU.org on September 10, 2015. Reproduced with permission.