As I write this article (December 2020), the third wave of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) infections is sweeping through Japan. The daily number of newly confirmed infection cases in Tokyo has surpassed 600. The number of serious cases is also increasing, raising concerns that the collapse of the healthcare system may be just around the corner. Under these circumstances, the government has decided to implement an additional economic package with a total project value of 73.6 trillion yen. In order to "maintain jobs, keep businesses going, achieve economic recovery, and open the way for new growth in such areas as green and digital technologies" (in the words of Prime Minister Suga), the government will allocate around 5.9 trillion yen in fiscal expenditure to measures related to the fight against COVID-19, around 18.4 trillion yen to the transformation of the economic structure, including digitalization, and around 5.6 trillion yen to measures to enhance national resilience against natural disasters. The government estimates that the new package will have the effect of boosting real GDP by approximately 3.6%. However, it cannot be denied that the package is a product of the "scale matters most" mentality. The priority has been put on massive fiscal spending intended to cover a demand shortfall estimated at 34 trillion yen (for the July-September quarter of 2020, on an annualized basis). Even though the economic package may temporarily stimulate demand by providing a macroeconomic shot in the arm, it is uncertain whether it will lead to "new growth" in the medium to long term. As indicated by the growing size of the government's budget deficit (the issuance of new government bonds), which has already exceeded 100 trillion yen, the fiscal condition also continues to deteriorate. Some people are optimistic about the future prospects for the fiscal condition of the country on the assumption that as the private sector continues to enjoy easy money (a fund surplus) for the moment, government bond yields will remain low. However, the so-called new normal that is represented by this kind of assumption means that general prices and wages will remain weak and that the employment situation will continue to be unstable. Therefore, I cannot help becoming pessimistic about the future course of the economy.

As economist Simon Kuznets once said, "there are four sorts of countries: developed, underdeveloped, Japan, and Argentina." In this argument, Kuznets characterized Japan as a country that achieved rapid industrialization and high growth. On the other hand, Argentina was characterized as a country which had once been an advanced country, but which had declined. As a matter of fact, before World War I, Argentina was among the 10 wealthiest countries in the world. In 1910, Argentina's per-capita GDP was 80% of the United Kingdom's and was higher than Germany's (Note 1). However, when prices of commodities such as wheat slumped due to the Great Depression in the 1930s, Argentina moved toward industrialization based on protectionism. The failure of that policy and ensuing political instability are considered to have led to the country's long-term decline. There is no guarantee that Japan will not follow the same path as Argentina although the circumstances are different. Indeed, in terms of per-capita GDP, Japan fell to 26th in the world in 2018, with its per-capital GDP already below the OECD average, and South Korea is close behind. It is not at all unimaginable that the COVID-19 crisis, coupled with structural problems such as the aging of society and a low birthrate, could lead to the "Argentinification" of Japan. It is not too much to say that in 2021, the Japanese economy is at a crossroads between revival and decline.

Then, what should be done? Japan has an abundance of household financial assets, worth more than 1,800 trillion yen. A large portion of those assets, which represent the fruits of Japan's past economic growth (stocks of wealth), has been used to absorb government bonds. The key will be whether Japan will be able to change course from this path and use the huge pool of funds to pave the way for future growth. Until now, financial institutions have required physical assets, including equipment and land, as collateral when extending loans to companies. In other words, loan eligibility has been measured in tangibles. However, in a digital economy where the significance of intangible assets (e.g., intellectual property) is growing, what contributes to economic growth is not tangibles, but human resources, namely people. What determines the success or failure of a company is management's competency. Therefore, it is desirable to develop a system that supplies funds based on the assessment of human resources¬ (people) instead of collateral (tangibles). Financial institutions, particularly regional banks, already require a keen eye in assessing business potential. I propose the scheme described below as a way to make sure that financial institutions pursue this approach.

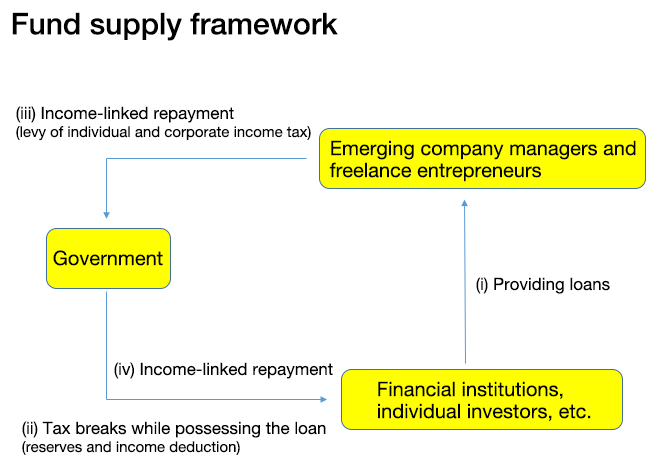

The scope of eligible borrowers under the proposed scheme would include not only managers of emerging companies but also freelance entrepreneurs with expert knowledge (borrowed funds may be used for investment in education as well as business operations). Under the scheme, financial institutions are responsible for utilizing their expertise in assessing the applicant parties and determining the viability of their operations. In principle, the scheme would focus on small-lot loans, such as those for which the upper limit on the loan amount per year is 4 million yen, with the maximum loan period set at five years (for a total loan amount of up to 20 million yen). In addition, the repayment period would start after a certain grace period, such as two years. Financial institutions would judge borrowers' loan eligibility and decide the loan amount after assessing their future potential instead of using current tangibles (collateral) as the yardstick. Meanwhile, in order to mitigate risk for lenders, the equivalent amount of funds as the loan amount would be at first set aside as tax-deductible loss reserves, an arrangement that reduces corporate income tax payment, and the return from the loan would be booked as profits (taxable income) at a later time upon redemption. In relation to this point, under the tax program to facilitate the concentration of business resources, the government has decided to allow reserves for future expenditures and losses to be included among tax-deductible losses in order to promote M&A activities involving small and medium-sized enterprises. Lenders may be individual investors. In other words, funds may be supplied in the form of direct finance, rather than indirect finance through financial institutions. Loan transactions under the proposed scheme would include cases in which wealthy individuals become "patrons" of emerging companies and freelance entrepreneurs. Financial institutions may encourage the supply of funds by acting as matchmakers between large-lot or small-lot individual investors (patrons) and emerging companies, and supply funds (Note 2). In this case, as in the case of preferential taxation for angel investors, a system which allows the deduction of the loan amount from the lender's income would be adopted. Borrowers, such as emerging company managers, would make repayments from their business profits. However, the terms of principal and interest repayments would be linked to borrowers' income rather than being fixed. That is because the return on investment in people is considered to move in tandem with those people's income. Schemes based on a similar approach include a scholarship loan program for which repayment is linked to income (Note 3). In the United Kingdom, people who take out scholarship loans are required to make repayments equivalent to 9% of their annual income after graduation assuming that the income amount is above the threshold of 21,000 pounds. Repayments are collected by tax offices at the same time as the levy of income tax. Following the example of this program, under the proposed scheme, the annual amount of repayments would be set at a certain percentage (e.g., 10%) of borrowers' taxable income and be collected at the same time as the levy of income tax to be transferred to lending financial institutions and investors. This arrangement would level out the burden on borrowers by granting a temporary repayment exemption when borrowers' businesses are making losses (when taxable income is negative). Putting tax offices in charge of loan collection would help determine borrowers' taxable income and secure repayments (Note 4). In addition, the repayment period would be set at a fixed duration (e.g., 15 years) and the total repayment amount (= the repayment ratio x taxable income x repayment period) would vary in accordance with the loan amount and the taxable income amount (the estimated amount at the time of loan provision) (Note 5). If a borrowers' business has failed, the total amount of funds to be repaid would be smaller than the normal principle and interest repayments (Note 6). On the other hand, successful businesses would return a larger amount of profits than the normal principal and interest repayments. This scheme would be a hybrid of loan and investment, so to speak. It would also be something like a GDP-linked bond (whose yield is linked to the GDP growth rate), with its repayment period corresponding to the bond's maturity. While the risk for financial institutions and investors higher because of the nature of the scheme, a portion of the risk would be shared with the government in the form of tax breaks granted at the time the loan is granted (Note 7).

Japan is faced with easy money and financial bottlenecks at the same time. In other words, necessary funds are not circulated to people with promising potential and business sectors led by such people. The proposed income-linked fund supply scheme (a loan-investment hybrid), under which the government, lenders (investors and financial institutions), and borrowers (emerging companies and freelance entrepreneurs) would share risk, is expected to help encourage investment in people (human resources).