Targeting has become a central question in economics and policy design. When policymakers face budget constraints, identifying appropriate beneficiaries for the policy is critical to maximizing policy impacts. Advances in machine learning and econometric methods have led to a surge in research on targeting in many policy domains, including job training programs (Kitagawa and Tetenov, 2018), social safety net programs (Finkelstein and Notowidigdo, 2019; Deshpande and Li, 2019), energy efficiency programs (Burlig, Knittel, Rapson, Reguant, and Wolfram, 2020), behavioral nudges for electricity conservation (Knittel and Stolper, 2021), and dynamic electricity pricing (Ito, Ida, and Takana, forthcoming).

Two commonly used approaches: targeting by self-selection or observed data

Economists generally consider two distinctive approaches to the design of effective targeting. The first approach is based on observable characteristics. In this approach, policymakers use individuals’ observable data to explore optimal targeting (Kitagawa and Tetenov, 2018; Athey and Wager, 2021). The second approach is based on self-selection. In this approach, policymakers consider individuals’ self-selection as valuable information when targeting certain individual types (Heckman and Vytlacil, 2005; Heckman, 2010; Alatas, Purnamasari, Wai-Poi, Banerjee, Olken, and Hanna, 2016; Ito, Ida, and Takana, forthcoming).

Which approach is desirable for policymakers is a priori unclear. For example, referring to the two distinctive approaches above as “planner’s decisions" and “laissez-faire," Manski (2013) summarizes,

“The bottom line is that one should be skeptical of broad assertions that individuals are better informed than planners and hence make better decisions. Of course, skepticism of such assertions does not imply that planning is more effective than laissez-faire. Their relative merits depend on the particulars of the choice problem."

—Charles F. Manski, Public Policy in an Uncertain World

A common view in the literature, reflected in this quote, is that the appropriate approach depends on the context, and therefore, researchers and policymakers need to decide which to use on a case-by-case basis.

Our new idea: develop a method that optimally integrates the two conventional approaches

In a new study, “Choosing Who Chooses: Selection-Driven Targeting in Energy Rebate Programs” (joint with Takanori Ida, Takunori Ishihara, Daido Kido, Toru Kitagawa, Shosei Sakaguchi, and Shusaku Sasaki), we develop an optimal policy assignment rule that systematically integrates these two distinctive approaches commonly used in economics.

Consider a treatment from which the social welfare gains are heterogeneous across individuals and can be positive, negative, or zero, depending on who benefits from the treatment. Our idea is that policymakers can leverage both the observable and unobservable information by identifying three types of individuals based on their observable characteristics.

When policymakers face budget constraints, identifying who should benefit from policy intervention is critical to the policy’s success for a variety of economic policies from social safety net programs to energy efficiency incentives. There are generally two ways to identify how to target programs: by choosing who can participate based on observable characteristics such as income and by letting people self-select. In this paper, we develop a data-driven method that optimally integrates these two approaches.

We applied this method to a field experiment in collaboration with the Japanese Ministry of Environment to determine the best way to target a residential electricity rebate program. The rebate program’s goal was to incentivize energy conservation in peak demand hours when the cost of electricity tends to be substantially higher than non-peak times. In doing so, there is a social (and household) benefit to conserving electricity, but also a cost in implementing the policy in terms of both government spending and household convenience. Therefore, the net welfare gain from a consumer can be positive, negative or zero. We randomly assigned 3,870 households to three groups: compulsory participation in the rebate program, compulsory non-participation in the program, and self-selection (i.e. households in this group were asked to decide on their own whether to participate).

Our field experiments show the advantage of our new method

Using the data from the field experiment, we estimate the optimal way to target the policy, the impact of that targeting on the policy’s success, and the impact of the policy on those who participated versus those who did not participate.

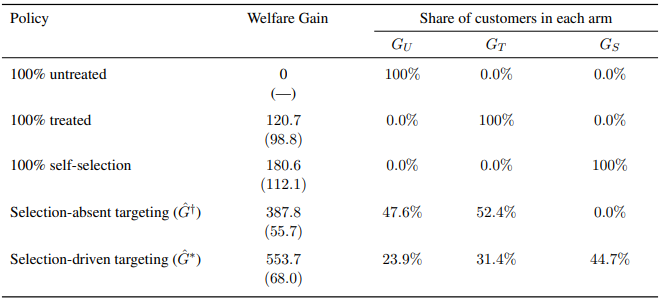

In the table below (Table 3 in the paper), we present the welfare performance for three benchmark policies without targeting (100% Untreated, 100% Treated, and 100% Self-selection), followed by the suboptimal and optimal targeting policies (selection-absent targeting and selection-driven targeting).

), and selection-driven targeting (

), and selection-driven targeting ( ). The column titled “Welfare Gain” shows the estimated ITT of welfare gain in JPY per household per season, with its standard error in parentheses. The monetary unit is given as 1 ¢ = 1 JPY in the summer of 2020.

). The column titled “Welfare Gain” shows the estimated ITT of welfare gain in JPY per household per season, with its standard error in parentheses. The monetary unit is given as 1 ¢ = 1 JPY in the summer of 2020.For each policy, we estimate the ITT of the welfare gain in JPY per household per season. We find that the 100% Treated policy induces a welfare gain of 120.7 per consumer, but the effect is not statistically significant. The 100% Self-selection policy results in a welfare gain of 180.6 per consumer and is marginally significant at p-value = 0.107. These results suggest that without targeting, we cannot reject that the policy’s net welfare gain can be zero.

Recall that our policy intervention induces both cost (from the implementation cost) and benefit (from the energy conservation), and therefore, the net welfare gain from a consumer can be positive, negative, or zero. This implies that we could be able to increase the policy performance by targeting policies.

Results in the Table suggest that the selection-absent targeting attains a welfare gain of 387.8 per consumer. Our algorithm identifies that 52.4% of consumers should be subject to the policy treatment, and 47.6% of them should not be subject to the treatment. Furthermore, we find that selection-driven targeting results in a welfare gain of 553.7 per consumer. With this policy, our algorithm identifies that 31.4% of consumers should be subject to the treatment, 23.9% of them should not be subject to the treatment, and 44.7% of them should self-select.

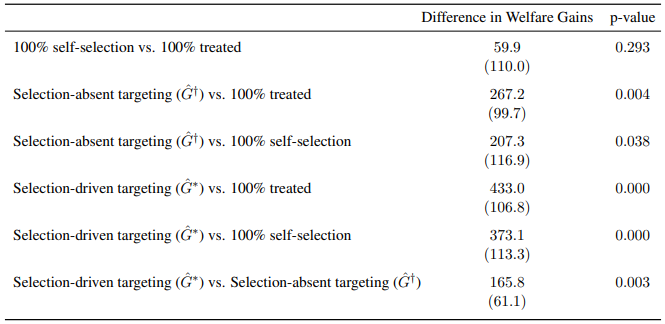

In the table below (Table 4 in the paper), we statistically test the null hypothesis that one policy’s welfare gain is larger than another policy’s welfare gain. The 100% S generates a larger welfare gain than the 100% T policy, but the difference is not statistically significant (p-value is 0.29). Both of our targeting policies (G† and G∗) generate statistically larger welfare gains than non-targeting policies. Finally, we find that the selection-driven targeting (G∗) results in a 43% (= 553.7/387.8 − 1) larger welfare gain than the selection-absent targeting (G†), and the difference is statistically significant at p-value of 0.003.

Our method can be applied to policies that balance efficiency and equity

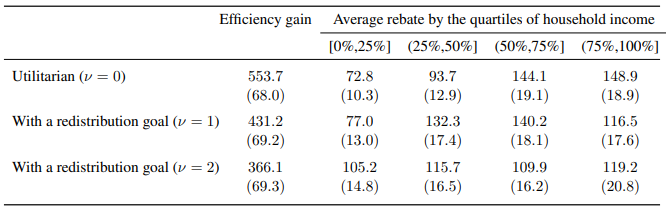

While the efficiency of the policy is important, it is also important that the policy be equitable. We emphasize that our framework is not restricted to the utilitarian social welfare function. To shed light on this point, we consider a social welfare function that balances the equity-efficiency trade-off. We use a framework developed by Saez (2002) and used by Allcott, Lockwood, and Taubinsky (2019) and Lockwood (2020). In this framework, the planner can include Pareto weights in a social welfare function to balance the equity-efficiency trade-off. We demonstrate that our method can quantify the optimal targeting for different degrees of redistribution goals. With this method, the planner can improve the equity of the policy at the cost of having a lower efficiency gain. We find that selection-driven targeting still outperforms selection-absent targeting even if we take into account redistribution goals.

In the table below (Table 7 in the paper), we compare the average rebate that would be distributed to consumers across the household income distribution. We find that the optimal policy would distribute more rebates to higher income households. That is, although this targeting maximizes the efficiency gain from the policy, it may not be appealing to policymakers who are concerned with equity. To address this equity concern, we also provide a way to balance the equity-efficiency trade-off. We find that allowing qualifying households to choose to participate is still more efficient and more equitable than automatically enrolling all qualifying households.