As a result of the spread of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19 pandemic), elementary, junior high and senior high schools in various regions across Japan were temporarily closed in March 2020 and thereafter. Many schools were unable to make sufficient preparations for the temporary closure, and as a result, the education of the children was largely left to families. As home learning depends significantly on the family environment, education inequality may have increased due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

This paper examines how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected inequality in child education based on an independent online questionnaire survey of 2,000 parents with children in elementary to senior high schools immediately after the state of emergency declaration was lifted nationwide (June 8 to 12, 2020) (Note 1).

Historical correlation between family circumstances and academic achievement as recorded before the COVID-19 pandemic

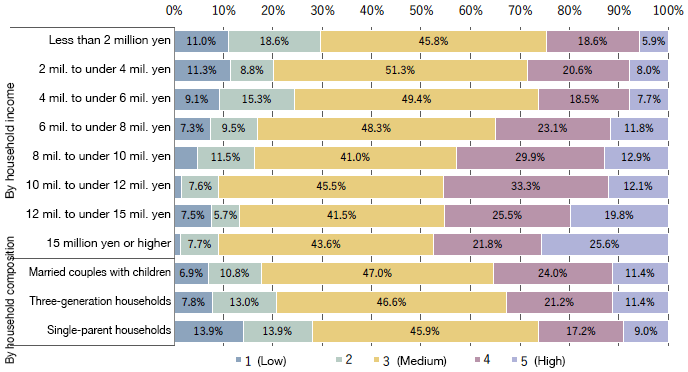

Before analyzing the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on inequality in child education, let us look at the correlation between the household income level, household composition and the academic achievement level before the COVID-19s pandemic. Figure 1 shows the academic achievement level of children by household income and by household composition in the school year 2019 (Note 2). The academic achievement level was lower among children from lower-income households and children from single-parent households (Note 3). The correlation between family circumstances and academic achievement level existed before the COVID-19 pandemic (Note 4).

Loss of education opportunities and widening of inequality due to temporary school closures

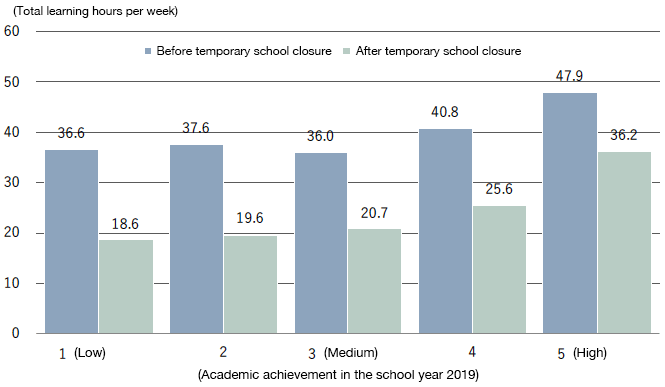

What effects have temporary school closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic had on education opportunities for children? Figure 2 shows total learning hours per week before and after temporary school closures by academic achievement level in the previous school year (school year 2019). Regardless of the academic achievement level before the pandemic, learning hours decreased after the temporary school closures. However, the decrease was larger among children whose academic achievement level was already low, while the decrease was limited among children with high academic achievement. One possible reason for the difference is that high achievers are more effective at learning autonomously. Another is that high achievers, who tend to be from higher-income households as shown in Figure 1, may have had greater access to alternative means of learning, such as cram schools and online education during the temporary school closures (Note 5).

Prolonged temporary school closure reduces learning hours even among children with high academic achievement

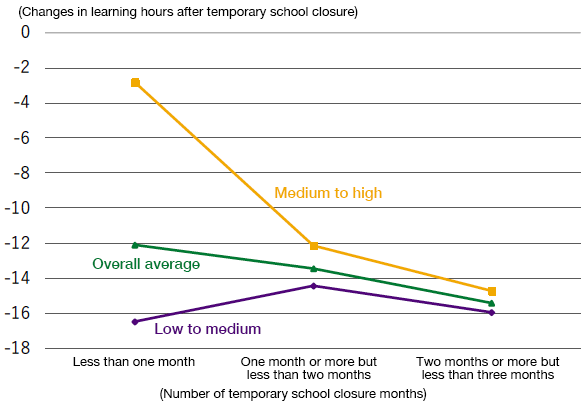

Figure 3 shows changes in learning hours after the temporary school closure by the number of closure months and by academic achievement level. The green line represents the overall average hours. This shows that the higher the number of temporary school closure months, the larger the decrease in the average learning hours. By academic achievement level, the decrease in learning hours was large among children with low to medium academic achievement (purple line) even in the case of short periods of temporary school closure. On the other hand, among children with medium to high academic achievement level (yellow line), learning hours decreased little in the case of short periods of temporary school closure, but the decrease was marked when the duration of closure was long (Note 6). These findings indicate that from the viewpoint of the duration of temporary school closure, the COVID-19 pandemic tends to widen education inequality. Given the negative effects of prolonged periods of temporary school closure on learning hours among all children, including those with high academic achievement, the overall academic achievement level among children may decline if temporary school closures last long.

Summary of the analysis results and policy implications

The results of the analysis of the questionnaire survey used in this paper show that because of temporary school closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic, learning hours decreased markedly among children whose academic achievement level was already low compared with among children with high academic achievement. Given the strong correlation between children's family environment, including the household income level, and their academic achievement, it may be said that education inequality increased due to family environment factors. We also found that a prolonged period of temporary school closure has the effect of gradually reducing learning hours even among children with high academic achievement.

Temporary school closures implemented at this time had particularly strong negative effects on children from lower-income households and children whose academic achievement level was already low before the pandemic. As those children are statistically more likely to find it difficult to learn on their own, it is necessary to correct inequality in the learning environment, enhance individualized instructions and upgrade online learning materials so that learning gaps can be closed.

The most important thing is to promptly grasp the situation of children and continuously review the effects of support measures. In other words, it is most important to continuously iterate the process of the PDCA (Plan, Do, Check and Act) cycle of evidence-based policy making (EBPM).