Changing paradigm in global politics

In recent years, political landscape has been changing drastically in many countries. In the United States, Donald Trump's administration has pushed the "America-first" agendas and prioritized the nation's interest above all else since coming to power in 2017. Regardless of existing trade or other agreements, the administration threatens trading partners with tariff increases or to walk away from negotiations if the conclusions are not favorable to the country. The administration does not shy away from trumpeting the "America First" or anti-globalization creed.

The idea of "our nation first" is not just limited to the U.S. The United Kingdom has been aiming to reclaim its national sovereignty by withdrawing from the European Union (EU). In many other countries, populist governments have arose, both on the left and the right, touting similar slogans and advocating for de-globalization to recover the economic benefits which they claim has been exploited by foreigners.

There has also been a backlash against the influx of refugees and immigrants. Resentment against such "internal globalization" has been on the rise in Europe, the U.S., and Latin America, supporting political forces willing to end social security and other benefits for the "free riders" and regain social benefits for their own domestic citizens.

These new political forces are different from those of the recent past.

For example, after World War II, Europe pursued regional political and economic integration through democratic process, although that involved each country to sacrifice its own national interest. For such Europe, the rise of countries prioritizing self-interest and advocating anti-globalization means a paradigm shift in the postwar order and a challenge against long-lived European unification efforts.

Even in originally rather democratic countries, such rifts between political authorities and the people have led the former to suppress the latter through undemocratic or authoritarian measures. The example includes Hong Kong, Venezuela, and Turkey.

Rodrik's political-economy trilemma

The current changes in political order can be comprehensively viewed through the lens of Dani Rodrik (2000)'s political-economy trilemma.

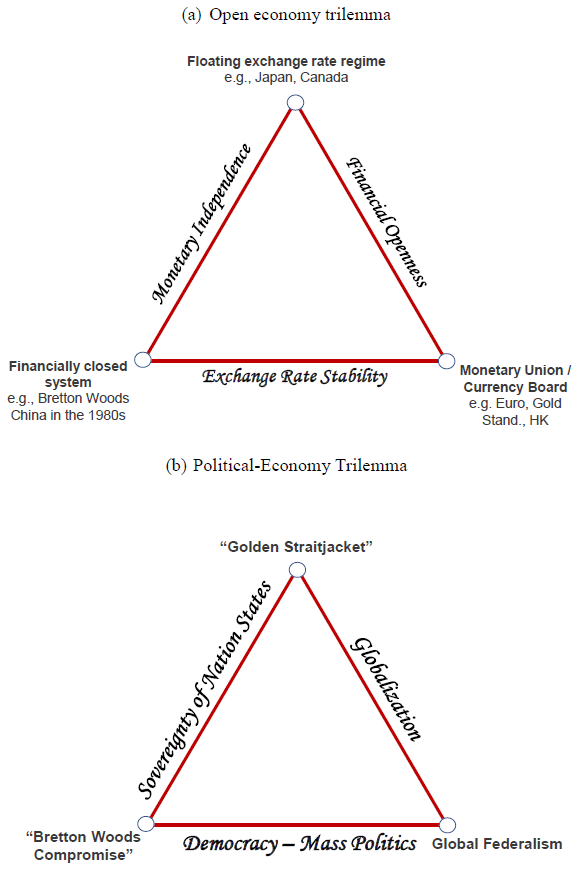

The word "trilemma" may remind international economists of the open economy trilemma.

The open economy trilemma, which has become a central theorem in international finance ever since its introduction by Mundell (1960) and Fleming (1961), states that a country may simultaneously choose any two, but not all, of the three goals of monetary policy independence, exchange rate stability, and financial market openness to the full extent (Fig 1–a).

Dani Rodrik applied this theory to political economy, asserting that among national sovereignty, democracy, and globalization, only two of these policy goals or forms of governance can be simultaneously achieved to the full extent, but not all three.

For example, the member states of the European Union (EU) each have democratic institutions of governance and are open to the globalized markets. However, each state cannot pursue its own national interest or assert its sovereignty (more fully than other member states do). In other words, the EU is a good example of a region marching toward global federalism (Fig. 1–b, bottom right corner of triangle).

Reclaiming its sovereignty in order to pursue its own national interest is exactly what the U.K. has been trying to accomplish by withdrawing from the EU. According to Rodrik's political-economy trilemma, the U.K. could have gone further toward fuller sovereignty either by restricting democratic policymaking or by limiting openness to the global economy (i.e., going from the bottom right corner of the triangle in Fig. 1–b toward the side of "national sovereignty"). Considering that Boris Johnson's administration is acting in strict accord with democratic process, sacrificing globalization would be the only way the U.K. could withdraw from the EU. Greater pursuit of a nation's national interest requires curtailing its access to international markets.

Other countries try to reap the benefit of globalization while still fully embracing their own sovereign statehood. These countries align themselves with international rules and standards when making their own, but they do not necessarily follow a fully democratic process for policymaking. Their domestic standards and rules are not based on democratically determined policies, but rather on those of multinational corporations and international organizations, or on treaties and agreements concluded by administrative bodies (i.e., bureaucrats who were not necessarily democratically elected). Thomas Friedman called this "the Golden Straitjacket" (Fig. 1–b; top of the triangle), which he describes as a state of affairs where "[a country's] economy grows and its [democratic] politics shrinks."

A country wearing the Golden Straitjacket can free itself from it by either pursuing a higher level of democracy or becoming less globalized.

It is also possible for a fully democratic nation to strengthen its national statehood and prioritize its national interest. However, such a country could not reap the benefits of globalization (Fig. 1–b; bottom left corner of the triangle). The Bretton Woods system, which existed from 1944 to 1971, allowed its member states to impose capital controls and barriers to international trade. From the perspective of the political-economy trilemma, this is a policy mix of full democracy and national sovereignty.

As these examples show, policy makers can simultaneously choose any two of the three policy goals of national sovereignty, democracy, and globalization, but cannot achieve all three to the full extent.

Empirical validity of the political-economy trilemma

Now, a natural question arises: Can the theorem of the political-economy trilemma be empirically proven with actual data?

Aizenman and Ito (2020) have constructed a set of the indexes, each one of which measures the extent of attainment of the three political-economic factors: globalization, national sovereignty, and democracy. The indexes are available for 139 countries between 1975 and 2016. Using these indexes, Aizenman and Ito tested whether the weighted average of the three indexes is constant. If so, i.e., if the indexes are to be found linearly correlated, that would mean that the three variables operate within a trilemma relationship, i.e., the trilemma is empirically valid.

The regression analysis shows that for industrialized countries, there is a linear negative association between globalization and national sovereignty, while the democratization index is statistically constant during the sample period. That means, for the industrial countries during 1975-2016, the political economy trilemma was mostly a dilemma between globalization and national sovereignty. For developing countries, a weighted average of the three indexes adds up statistically to a constant with positive and significant weights, indicating they are in a trilemma relationship, as Rodrik claims.

Closely examining the development of the three indexes over the sample period reveals that for industrialized countries, while the level of democracy is stable and high, there is a combination of rising levels of globalization and declining extent of national sovereignty from the 1980s through the 2000s, mainly reflecting the experience of European industrialized countries. Developing countries, in contrast, experienced convergence of declining sovereignty and rising globalization and democratization around the same period. Emerging market economies experienced rising globalization and democratization earlier than non-emerging market economies with all the three variables converging around the middle.

The possible impacts of the three policy goals on political and economic stabilities

Lastly, what kinds of impacts could these three policy goals (national sovereignty, democracy, and globalization) have on actual politics and economics? Aizenman and Ito performed a regression analysis to examine how the three trilemma variables can affect political stability and economic stability.

Their results indicate that (a) that more democratic industrialized countries tend to experience more political instability; and (b) that developing countries tend to be able to stabilize their politics if they are more democratic. The lower level of national sovereignty an industrialized country embraces, the more stable its political situation tends to be. Globalization brings about both political and economic stability for both groups of countries.

Developed countries, particularly the U.S. and the U.K., are now asserting their national sovereignty, touting policies that prioritize their national interests and an anti-globalization stance. If the regression analysis is correct, such policies could increase political instability and the probability of financial crisis. Furthermore, if a developing country takes an anti-democratic or an anti-globalization stance, it could face more political or economic instability.

Let us see what will happen.