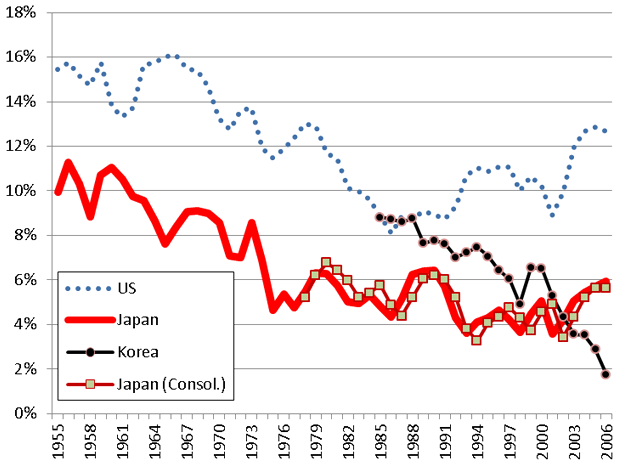

Japanese firms invest in research and development (R&D) on a level comparable to that of their U.S. counterparts. They possess a high-quality workforce and receive decent management practice scores for organizational and human resource (HR) management. Yet, they fall significantly behind U.S. firms when it comes to earning power. Figure 1 below, which I calculated along with Senshu University School of Economics Associate Professor Kim Young Gak, plots the average ratio of operating income to sales for Japanese, U.S., and South Korean listed companies from 1955 to 2006. As it shows, the operating income ratio of Japanese firms never surpassed that of U.S. firms over the entire 50-year period, and trended downward until 2003.

Why do Japanese firms have poor earning power?

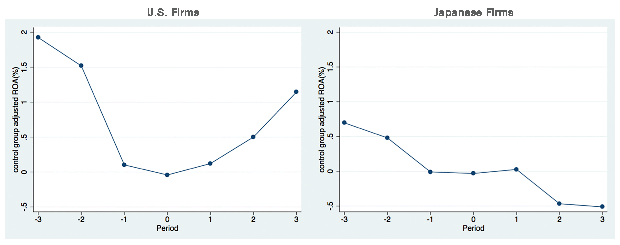

One of the reasons behind Japanese firms' poor earning power is their corporate structure whereby the chief executive officer (CEO) is the one who is responsible for corporate management. To verify whether the CEO is attributable to Japanese firms' poor earnings performance, I examined performance fluctuations of Japanese and U.S. firms before and after a change in company leadership. Empirical analysis conducted by Izumi and Kwon (2015) shows that both Japanese and U.S. firms suffer corporate performance decline leading up to the forcible replacement of the CEO, and that the replacement results in performance recovery for U.S. firms but not for Japanese firms.

[Click to enlarge]

Figure 2 above shows the changes in the return on assets (ROA) for Japanese and U.S. firms before and after a corporate leadership change. If performance decline is attributable to external factors on the industry or corporate level, it may be able to be recovered without a leadership change. To deal with this possibility, I employed the econometrics matching approach for the analysis. In other words, I chose firms with no forcible leadership change experience that share similar characteristics with those that have undergone forcible leadership change, and compared the performance of the two groups. The results strongly indicate that CEOs of U.S. firms aim to maximize corporate performance, while CEOs of Japanese firms prioritize long-term corporate survival over performance maximization. This hypothesis is verified by results showing that U.S. firms substantially cut down on the scale of assets and workforce to increase ROA following leadership changes, whereas Japanese firms tend to work on reducing liabilities. Despite excelling in technologies, organizational management, and HR management, Japanese firms seem to have lower earning power because CEOs, who are responsible for corporate management, do not prioritize profit maximization. Such tendency leads to a loss of shareholders' equity and inefficient usage of firm resources, causing a major negative macroeconomic impact.

What should be done to foster earning power?

The secret of Japanese firms' strength has been described as lifetime employment, seniority-based wages, and company-specific labor unions. These elements of Japanese strength are on the premise of long-term corporate survival. To safeguard them, Japanese firms have demonstrated a tendency to choose CEOs from within their own ranks who are familiar with the company and have a risk-aversion stance, or from their immediate stakeholders (creditors, parent companies). As long as this tendency continues, Japanese firms are less likely to exert their full potential and generate earnings which can measure up to their performance. To improve Japanese firms' performance and pull them out of the "lost two decades," it is necessary to carry out the following reforms:

First, just as U.S. firms' CEOs would opt to cut jobs to boost corporate performance after leadership changes, Japanese firms must have a flexible labor market and other complementary systems such that their CEOs can execute management rights with responsibility.

Next, it should be noted that the United States has a labor market for CEO resources who specialize in business management, whereas there is hardly such a labor market in Japan. The presence of a labor market for management specialists sets the United States far ahead of Japan in terms of the scale of HR pool for potential company leaders. This could negatively affect corporate performance after leadership changes. A CEO moving on to another company after leading the first company's recovery from poor business performance is normally a one-off case. There is hardly any such case of company leaders moving on to another business. There is a problem seen with firms such as Sony Corporation and Sharp Corporation which both selected a new CEO from within their own ranks following a business downturn.

Finally, main financing banks are reluctant in approving high-risk, high-return investments because of their primary goal of collecting debts. It also should be noted that it is difficult for boards of directors, which comprise only insiders, to be independent and pursue profit maximization in company management. The Companies Act has been amended to encourage the appointment of outside directors to overcome the above mentioned issues. Through these system reforms, it is necessary to overhaul the Japanese firms' shareholder structure which is based on cross-shareholding with main financing banks, and the structure of their boards of directors.